I have always loved Hitchcock and regard him not merely as an auteur, but as a creator who gave birth to an entirely new world—a galaxy where countless filmmakers have lived and built their own planets. Among the great Hitchcock scholars worldwide, a few of the Iranian critics such as Parviz Davaei, Kiumars Vejdani, and Bahram Beyzaie hold a very special place in my view. For all Hitchcock enthusiasts, I highly recommend the book Hitchcock in the Frame, the result of a long conversation with Bahram Beyzaie about Hitchcock’s cinematic language. (the book is in Farsi and we will translate and post a few chapters of it in CWB in the neear future)

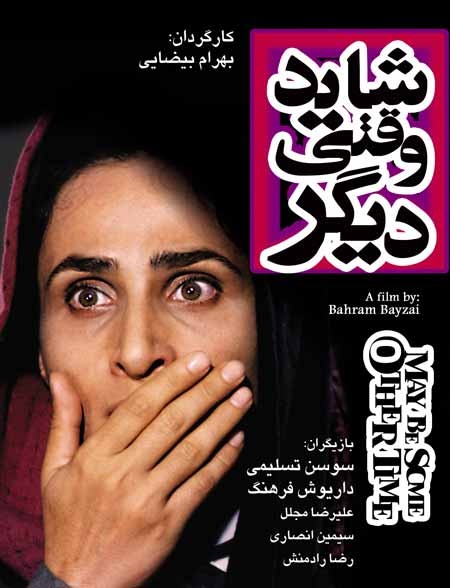

Recently, after many years, I revisited Beyzaie’s Maybe Some Other Time (Shayad Vaqti Digar, 1987), and the following essay is born from that encounter.

Maybe Some Other Time, directed by Beyzaie in 1987, is undoubtedly one of the most mysterious, influential, and controversial films in the history of Iranian cinema. Like much of Beyzaie’s work, it not only resonates within the social and cultural fabric of Iran but also enters into dialogue with the history of world cinema. Beyzaie has always been a filmmaker deeply attached to the mythological and cultural heritage of Iran, while simultaneously maintaining a global outlook. His cinematic language is woven into conversation with the greatest traditions of world cinema. In Maybe Some Other Time, this global perspective is revealed most strikingly in its relationship with Hitchcock’s cinematic language.

Hitchcock was the master of suspense, the architect of perspective, and the great manipulator of truth and lies in storytelling. Time and again he placed the audience in the liminal space between knowing and not knowing, using color, space, and shadow as narrative tools, and demonstrating that “truth” itself is often nothing more than an illusion. Beyzaie employs many of these strategies, but places them in the social fabric of 1980s Iran, creating a film that is simultaneously Iranian and universal, continuing Hitchcock’s tradition while also resisting it.

The protagonist is Modabber, played by Dariush Farhang, a man who works as a narrator for television documentaries. At first glance, it is an ordinary job: reading words that are meant to give meaning to images for viewers. But Beyzaie turns this profession into a profound metaphor. Modabber is someone who constructs reality through words—his voice determines the meaning of images, even if those images remain ambiguous. This choice is deliberate, for the film’s central question is precisely this: is what we see the truth, or is it always a reconstruction subject to distortion and error? From the very beginning, Beyzaie warns us that in this world, truth is neither self-evident nor trustworthy.

Opposite Modabber stands the female lead, Kian, played by Susan Taslimi. Kian’s life is shrouded in mystery and doubt. She has a past partly concealed from us, and her husband gradually grows suspicious of her. Kian is not simply the object of the male gaze, but also a subject in her own search for identity and truth. Here Beyzaie draws inspiration from Hitchcock but rewrites the pattern. In Hitchcock’s cinema, women are often either enigmas to be solved or helpers in the male hero’s quest. In Vertigo, Kim Novak is the puzzle itself; in Rear Window, Grace Kelly assists the male protagonist in uncovering a secret. In Beyzaie’s film, however, the woman is central to the narrative. She is both the suspected figure and the seeker of truth, embodying the film’s philosophical and existential weight.

The film’s most famous Hitchcockian moment comes when Modabber, while watching a documentary to write its narration, sees an image of his wife Kian sitting in a red Paykan beside an unknown man. This is the moment that pulls him into a vortex of doubt. Seeing his wife in that car blurs the line between reality and imagination. Is the image truthful? Was she truly there, or is it a misperception, a misunderstanding? From that instant, Modabber cannot let go of the question, and no image remains trustworthy to him. The red car, as critics have noted, is symbolic: danger, passion, blood, and threat. Hitchcock himself often used the color red with these connotations—in Vertigo, in Spellbound, and elsewhere. Beyzaie transplants this symbolism into 1980s Tehran, reinterpreting it in his own cultural and social context.

From that moment forward, doubt overshadows the entire film. Modabber can no longer even trust his profession—his narration of images. Every picture becomes suspect; every scene raises new questions. This recalls Hitchcock’s Shadow of a Doubt, in which suspicion seeps into the closest personal relationships. But the difference is crucial: Hitchcock eventually resolves the doubt with revelation, while Beyzaie leaves truth hidden in ambiguity. Doubt here is not resolved but becomes the characters’ permanent destiny.

Beyzaie also makes Tehran itself a character in the film, much like Hitchcock’s use of architecture. The city is not passive background but an active, threatening presence. Streets, nameless alleys, cold buildings, and looming walls form a labyrinth in which the characters are trapped. His camera often frames them within constricted spaces, echoing Hitchcock’s Rear Window with its multiple windows concealing hidden secrets. Tehran in Maybe Another Time is a city scarred by history, where mysteries multiply rather than resolve.

Structurally, the film mirrors the logic of dreams, suspicion, and nightmare. It is not linear but filled with repetitions and dead ends. Characters encounter signs they believe to be clues to the truth, yet these never lead to certainty. This recalls Vertigo, where the protagonist circles endlessly in pursuit of an unattainable reality. The difference is that Hitchcock eventually reveals the secret, whereas Beyzaie never does. The film ends with the same uncertainty it began with. Has Modabber truly seen what he believes? The audience, like him, is left in doubt. This open ending elevates suspense from the psychological to the philosophical level.

At the same time, the film asks a profound question about cinema itself. Modabber, tasked with giving words to images, suddenly sees himself entangled within them. The experience is disorienting: is this truth or illusion? Can words reveal reality, or do they only deepen the uncertainty? Beyzaie poses an ontological question about cinema and media, much as Hitchcock did in Rear Window: is seeing alone enough to know? Beyzaie pushes further: does narrating something prove its truth?

Maybe Some Other Time ultimately stands as a luminous example of creative dialogue between an Iranian filmmaker and the legacy of Hitchcock’s cinema. Beyzaie, using suspense, color, shadow, setting, and nightmare logic, builds a world where truth is always out of reach. Yet he reconstructs these elements within the cultural and social fabric of 1980s Iran, producing a film that, while reminiscent of Hitchcock, is unmistakably his own. Modabber—with his profession, the haunting image he has seen, and his endless doubt—becomes a symbol of a society whose historical memory is wounded, where truth can only be reconstructed through uncertain words and elusive images. The film’s open ending leaves us with a haunting message: perhaps truth will never fully reveal itself. Perhaps it will always remain one step ahead of us. Perhaps—some other time.