Trifole establishes its world from the earliest moments as a story about the slow disappearance of a way of life, one rooted in the Langhe region of Italy, where the tradition of truffle hunting has been passed down for generations and now stands on the verge of extinction. The narrative centers on Igor, an aging truffle hunter whose knowledge of the land runs deep, and his granddaughter Dalia, a teenager who returns to the family home not with her mother, now a busy surgeon who left the village years ago, but in her place to assist her grandfather. This setup brings two fundamentally different worlds into direct confrontation: the calm, experiential world tied to nature, and the fast, urban life defined by speed, work, and a severed connection to roots.

Through subtle details in Dalia’s behavior, the film reveals a quiet anxiety, an unease shaped by urban upbringing, visible in her silences, glances, and hesitant responses to the natural environment. Raised in London within a system built on order, speed, and competition, she suddenly finds herself exposed to a more elemental form of calm upon returning to her mother’s childhood village. It’s a calm her mother once abandoned, yet now sees as the very remedy her daughter needs. This return is not a leisurely visit but a generational encounter with something lost yet still alive in the unconscious.

At the narrative’s center stands Igor, whose presence embodies more than the remnants of a rural generation; he carries a lived knowledge of nature’s cycles. The film illustrates how this knowledge, formed through observation, experience, and a lifetime spent close to the soil, is at risk of vanishing. His bent body, the quiet of the old house, and his effort to preserve traditional truffle-hunting methods all gradually underline the erosion of this world.

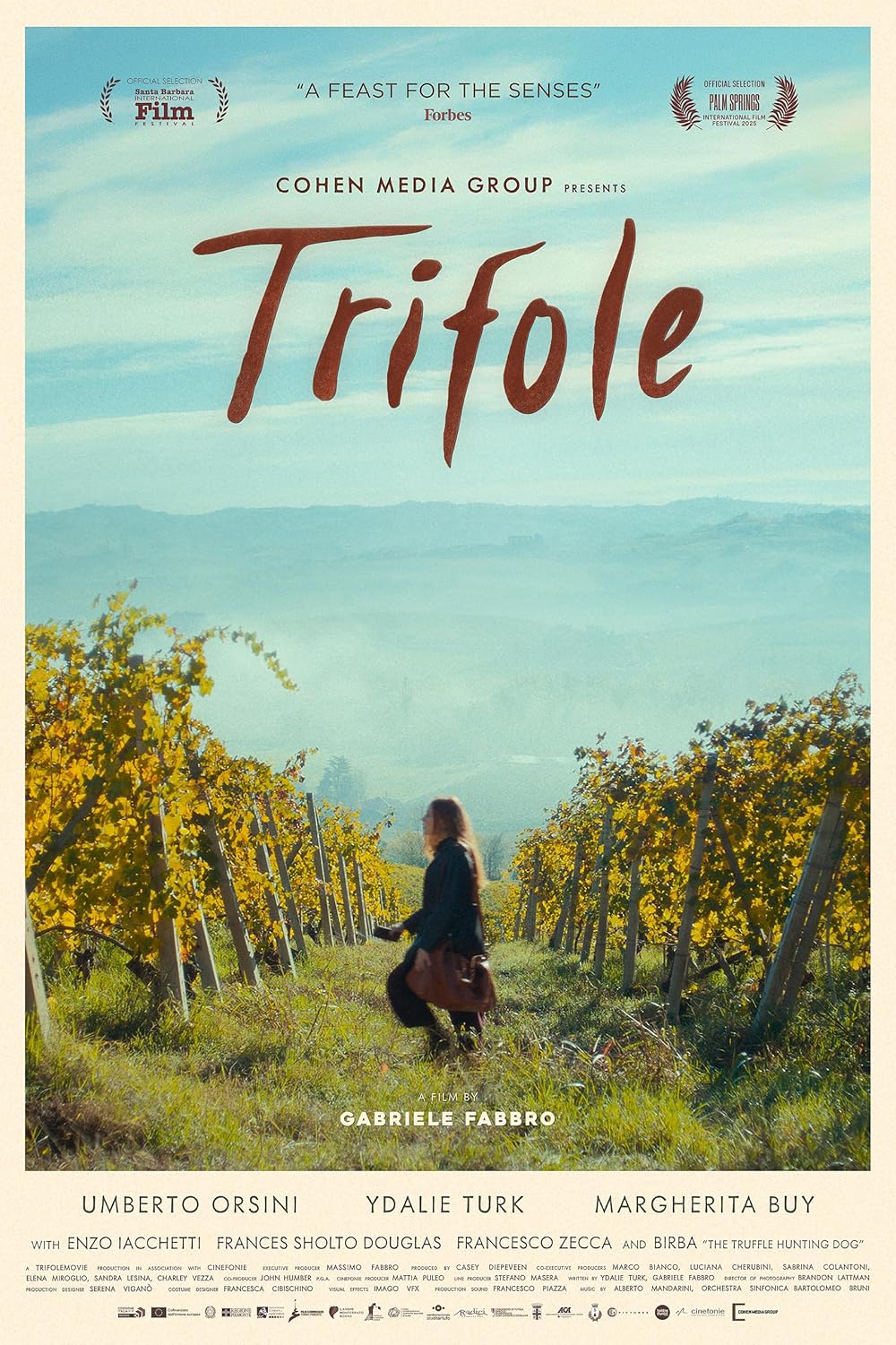

One of the film’s most striking elements lies in its formal approach and framing. The director relies heavily on expansive long shots and precise compositions to articulate the relationship between human beings and their environment on a larger scale. Many shots are captured from a significant distance, emphasizing the smallness of human presence against the vastness of nature, not as decoration or aesthetic flourish, but as an extension of the film’s core idea about humanity’s place in the natural world. The cinematography, shaped by natural light, raw color palettes, and layered depth of field, conveys a sense of continuity, stillness, and age. This formal strategy places the viewer not as a distant observer but as someone present in the space, as if the forest itself were a character and the camera merely facilitating an encounter.

In its middle section, however, the film steps away from its initial realism and moves into a more mythic, almost dreamlike realm. While this shift aligns with Dalia’s subjective experience of confronting the unknown in the forest, it occasionally affects the narrative’s cohesion. The filmmaker’s attempt to visualize the adolescent character’s inner world through minimal gestures and impressionistic moments yields visually engaging scenes but is less dramatically effective than the segments anchored in her interaction with Igor.

The truffle auction sequence marks the film’s thematic peak. Without overt commentary, the scene delineates the distance between the earthy origins of truffles and their commodification within urban luxury markets. Through meticulous mise-en-scène, attention to detail, and the contrast between the cold lighting of the auction hall and the forest’s darkness, it becomes one of the film’s strongest examples of directorial control.

Ultimately, Trifole is less about truffle hunting itself than about intergenerational relationships and the possibility of returning to a natural world that is slipping away. The bond between Igor and Dalia is not sentimental in the conventional sense; it is a form of inheritance—one that finds meaning only through lived experience in nature.

Through her time with her grandfather, Dalia regains a part of her identity that her mother abandoned in her pursuit of progress, but which the next generation still quietly needs.

Though the film’s narrative occasionally becomes fragmented, its portrayal of the human–nature relationship, its spatial imagery, and its depiction of the tension between tradition and modernity make it a substantial and compelling work. Trifole suggests that some worlds may fade from memory but never completely disappear; all it takes is for the next generation to pause and look back at the land.