Bashu, The Little Stranger remains one of the most luminous works in the history of Iranian cinema and its recognition at the Venice Film Festival is both a triumph of artistic integrity and an affirmation of the universal power of storytelling that transcends borders, languages, and cultural boundaries. Bahram Beyzai’s masterpiece is at once a tale of exile, survival, motherhood, cultural collision, and above all, human resilience, told with a poet’s sensibility and a dramatist’s sharp instinct for human conflict. That this film, made decades earlier, has returned to the center of global cinematic attention and secured the Golden Lion is a testament to its timelessness, its ability to speak to crises that have never ceased—wars that displace children, societies that struggle to embrace outsiders, and individuals who must bridge gaps of language, ethnicity, and trauma in order to find a new form of family. To review Bashu, The Little Stranger today is not merely to revisit a classic, but to recognize how prophetic Beyzai’s vision was, how urgently relevant his storytelling remains, and how beautifully the film crafts its aesthetic of both pain and hope.

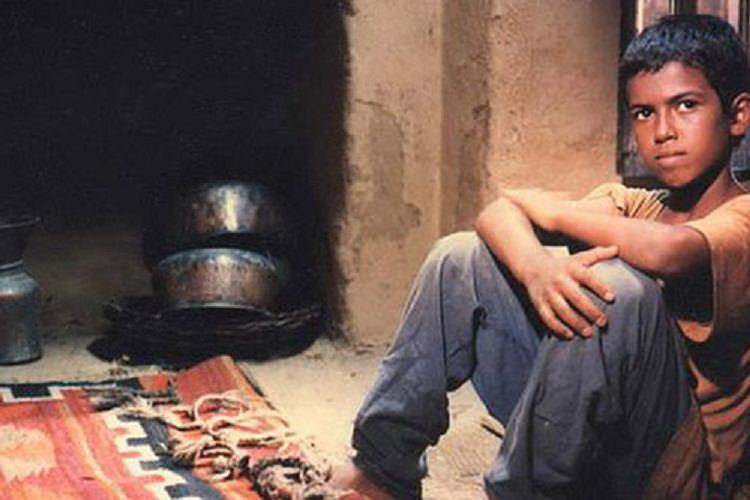

The story follows Bashu, a young boy from the war-ravaged south of Iran whose family is killed during the Iran–Iraq war. Traumatized, silent, and displaced, he flees northward by chance, eventually arriving in a lush Caspian village where his dark skin, his southern dialect, and his silence mark him as an alien. There he encounters Naii, a woman struggling to manage her land and her children while her husband is absent, likely fighting at the front. Naii is practical, earthy, resilient; she takes in Bashu at first out of instinct and later with maternal warmth, even as her neighbors question and resist the presence of this outsider child. What unfolds is a story of cautious adoption, of gradual acceptance, and of the difficult but profound process of stitching together a fractured sense of family across lines of race, class, and geography. In Bashu’s silence and Naii’s stubbornness we find two archetypal figures—one of the orphan who has lost his language, and one of the mother who must redefine her capacity for love.

What makes the film astonishing is the way Beyzai frames this intimate story within a larger cosmological and cultural frame. He does not simply tell us about a war orphan and a mother; he gives us Iran as a complex, multi-ethnic land where dialects and colors shift, where myths whisper through the forests, and where human beings are both bound by tradition and called upon to expand their moral imagination. The contrasts between the hot, desert-like south and the humid, green north are photographed with a painter’s eye, reminding us that geography is destiny in Iran, and that the child’s journey is not only from war to peace but from one cultural universe to another. Beyzai, as always, infuses the narrative with a sense of the theatrical and the mythical: Bashu’s visions of his dead mother, who appears ghostlike in the fields; Naii’s invocations of spirits and superstitions; the animals that surround and sometimes seem to comment on the human drama. The result is a film that is rooted in realism yet constantly reaches into allegory, where every gesture carries the resonance of national trauma and universal myth.

The performances anchor this poetic vision with astonishing humanity. Adnan Afravian as Bashu gives one of the most haunting child performances in cinema, a mixture of innocence, fear, and stubborn will to survive. His silence is eloquent; his wide eyes carry both terror and determination. Susan Taslimi as Naii is extraordinary, perhaps delivering the greatest female performance in Iranian cinema: earthy, stubborn, practical, sometimes harsh, yet ultimately embodying the inexhaustible force of maternal love.

She is not idealized; she is portrayed with all her contradictions and limitations, which makes her eventual acceptance of Bashu all the more powerful. Around them, the villagers and family members are drawn with folkloric precision—sometimes comic, sometimes cruel, sometimes compassionate. Beyzai directs his cast not to act for realism alone but to move within the rhythms of ritual and myth, which is why the film often feels like a fable even as it shows us the mud, the labor, and the sweat of daily rural life.

One of the most striking aspects of Bashu, The Little Stranger is its approach to language. Bashu speaks Arabic at first, then southern Persian dialect, while Naii and the villagers speak Gilaki. Their initial inability to communicate dramatizes the fractures within the Iranian nation itself—ethnic, linguistic, and cultural divides that war and displacement only intensify. Yet gradually, through gestures, through shared labor, through the simple acts of eating together and working side by side, a new language of affection is born. Beyzai is subtle in showing how integration does not come through erasure but through addition: Naii learns some of Bashu’s words; Bashu learns hers; their mutual vocabulary is a symbol of a future Iran in which difference need not be feared but embraced. This linguistic layering is also profoundly cinematic, since the audience is invited to experience the strangeness of hearing multiple dialects and to discover, like the characters, the bridges that can be built across them.

Visually, the film is a feast. Beyzai and his cinematographer craft frames that breathe with natural light, capturing the green of the Caspian fields, the mud of the rice paddies, the sweat of physical labor, and the luminous darkness of night rituals. The juxtaposition of the south and the north—Bashu’s sun-burnt memories versus Naii’s rain-drenched landscapes—serves as a metaphor for the richness of Iranian geography and culture, but also for the harsh contrasts that Bashu must reconcile within himself. The use of animals—goats, cows, birds—as constant companions in the mise-en-scène is not merely folkloric but symbolic: they reflect the instinctive, natural rhythms of life that continue despite war and displacement. They also serve as silent witnesses, sometimes more compassionate than the villagers themselves, to the plight of the stranger child.

Thematically, Bashu is revolutionary in Iranian cinema for its treatment of race and ethnicity. The dark-skinned southern boy in a northern village becomes a living test for a society’s capacity to accept the Other. At a time when Iranian cinema often skirted around issues of ethnic diversity, Beyzai placed it at the center of his narrative. The villagers’ suspicion of Bashu, their fear that he carries disease, their hostility to his difference, all mirror larger social prejudices that are not unique to Iran. And yet, the film’s ultimate embrace of Bashu, symbolized by Naii’s insistence on calling him her son, delivers a radical affirmation: that humanity, not bloodline, defines family; that survival requires solidarity across divides; that love can and must expand to include the stranger. This theme resonates profoundly today in a world still grappling with refugees, migrants, racial tensions, and the politics of belonging.

Beyzai’s work also stands out for its gender politics. Naii is not a passive mother; she is an active farmer, decision-maker, protector. Her husband is absent; she carries the weight of survival on her shoulders. In many ways, the film is as much about her as about Bashu, for she must overcome not only the prejudices of her community but also the limitations imposed on her as a woman. That she chooses to defy convention, to expand her family to include Bashu, is both a personal act of courage and a political act of redefinition. She becomes a symbol of the possibility of a new maternal identity—one that is expansive, inclusive, and transformative.

Through Naii, Beyzai pays tribute to the women of Iran who hold families and communities together in times of war and displacement.

The structure of the film also reflects Beyzai’s theatrical background. The narrative is episodic, unfolding in rhythms rather than in conventional plot turns. There are repeated motifs: Bashu’s visions of his dead mother, Naii’s incantations to ward off spirits, the children’s labor in the fields, the slow process of neighbors’ acceptance. Each repetition deepens the symbolic resonance, reminding us that we are watching not just a story but a ritual of acceptance, a myth enacted for a modern audience. The slow pace, the attention to gestures and silences, the refusal to offer easy resolutions—all these mark the film as a work of art that trusts the viewer to inhabit its rhythms, to listen, to wait, and to discover meaning in the spaces between words.

At Venice, the recognition of Bashu, The Little Stranger is also recognition of the Iranian cinema tradition that has long captivated the world. From Kiarostami to Farhadi, Iranian filmmakers have often offered minimalist, poetic explorations of life under constraint. Beyzai, however, represents a slightly different strand—more theatrical, more overtly mythological, more interested in the deep cultural roots of Iranian identity. That his film now stands on the world stage with new honors suggests that audiences are not only interested in the neorealist or minimalist strand of Iranian cinema but are ready to embrace its theatrical, mythical, and allegorical voices as well. It is also a reminder of how courageous Iranian filmmakers have been in addressing themes of war, displacement, gender, and ethnicity under difficult circumstances of censorship and political control.

The film’s final sequences remain among the most moving in world cinema. When Naii fully acknowledges Bashu as her child, the emotional power lies not in sentimentality but in the recognition that love has expanded, that a new form of family has been created, that trauma has not been erased but has been given a home. Bashu’s smile, hesitant but real, becomes a symbol of possibility. It tells us that the wounds of war, though never healed, can be soothed by solidarity, by compassion, by the willingness of one person to open her door and say, “You belong here.” Few films achieve such profound emotional truth with such simplicity.

To write positively about Bashu, The Little Stranger is not difficult; the challenge is to capture the full extent of its richness. It is a film of images that remain engraved in memory: the boy running through rice fields with visions of his dead mother hovering beside him; Naii planting rice seedlings while children help at her side; the villagers gathering with suspicion, their murmurs like a Greek chorus of prejudice; Bashu’s wide eyes staring at a world that does not yet know what to make of him. It is a film that rewards repeated viewings, each time revealing new layers of symbolism, new subtleties of performance, new resonances with the viewer’s own world. It is, in short, a masterpiece.

That it should win the Golden Lion at Venice this year is more than an award for a single film; it is a statement about the enduring relevance of cinema itself. In a world of global migration crises, wars, and rising xenophobia, a film made in Iran decades ago tells us more about who we are and who we could be than many contemporary works. It demonstrates that cinema, when rooted in its own culture yet open to universal themes, can achieve immortality. Beyzai, in crafting Bashu, The Little Stranger, gave the world a story that could belong to any displaced child, any courageous mother, any community confronted with the challenge of the stranger at its gate. By honoring this film, Venice honors not only Beyzai and Iran but the very principle of cinema as a bridge between cultures and as a voice for the voiceless.

Bashu, The Little Stranger is a rediscovered classic.