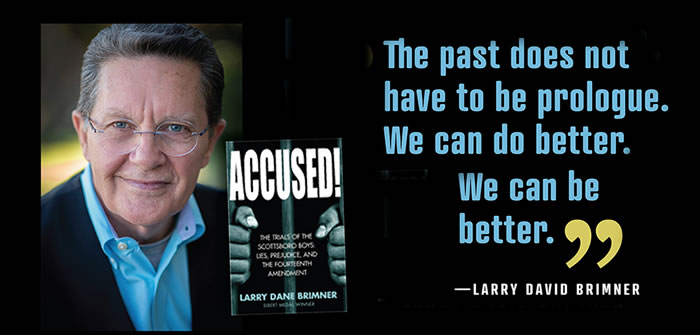

In this Op-Ed, Larry Dane Brimner explains his writing process for his forthcoming book, Accused!: The Trials of the Scottsboro Boys: Lies, Prejudice and the Fourteenth Amendment (Gr 8 Up, Calkins Creek/Boyds Mills & Kane) and how the book shares unfortunate parallels to the state of today’s justice system.

“When I first began Accused!: The Trials of the Scottsboro Boys: Lies, Prejudice, and the Fourteenth Amendment, I had no idea how relevant the book would be to today’s political and social reality. My nonfiction books are contracted long before I sit down at my keyboard to write them. Accused! was contracted in March 2016. Before it was picked up by my publisher, I’d spent a good year conducting preliminary research and thinking about approaches to the story.

The book, in concept at least, predated the Trump administration’s outright animosity to people of color, the “Unite the Right” rally held in Charlottesville, and the visible reemergence of white nationalism. I had hoped that with the election of Barack Obama, American society had made progress in race relations. Yet, because of the kinds of books I research and write—social justice and civil rights—I knew that whatever progress we’d made, it was not enough. The events that unfolded in Scottsboro, AL in 1931 share obvious parallels with the systemic racism and discrimination we see today.

When further researching this topic, I was struck by the injustices heaped upon nine young African American men—from false accusations of rape to inadequate and ill-prepared legal counsel, to the speed of their trials, to the prejudiced, all-white judges and juries, to the pre-determination of guilt. The youths ranged in age from 13 to 20. What mattered most in their trials wasn’t an assumption of innocence until proven guilty, but rather the color of their skin. Haywood Patterson, one of the youths wrongly convicted of raping two white women, wrote in his 1950 autobiography Scottsboro Boy, “I was convicted in their minds before I went on trial. . . . All that spoke for me on that witness stand was my black skin—which didn’t do so good.”

The same prejudice exists in the United States today. A recent example is the case of the Central Park Five. Five black and Hispanic boys, between 14 and 16 years of age, were wrongfully accused of beating and raping a white female jogger in New York City’s Central Park in 1989. Fearing that their lives were in jeopardy, they all admitted guilt after being subjected to hours of manipulative interrogation tactics. One detective, Thomas W. McKenna, admitted on the stand that he lied to one of the defendants when questioning him. As in the Scottsboro case, their parents were not present during questioning. Out of the five, four of the accused made videotaped confessions. The young men later recanted their confessions. After two trials, the second before a racially mixed jury of three Hispanics, five whites, three blacks, and one Asian, they were found guilty despite no DNA evidence linking them to the crime. They served between six and 13 years in prison, time which unalterably changed their lives. The case prompted Donald Trump, then known for being a real estate developer, to take out full-page advertisements in local newspapers calling for New York to reinstate the death penalty. In a 1989 interview with Larry King, he said, “Maybe hate is what we need if we’re gonna get something done.” As in the case of the Scottsboro Boys, white people called for a public lynching.

In 2002, the five young men in the Central Park case were exonerated. The real rapist, Matias Reyes, had come forward and his DNA matched that taken from the victim. He was also able to tell the police details of the attack that wasn’t common knowledge. After the Central Park Five were released from prison, Yusef Salaam, one of the Five, said, “I look at Donald Trump, and I understand him as a representation of a symptom of America. We were convicted because of the colour of our skin. People thought the worst of us.”

Salaam’s comment echoes the one made by Haywood Patterson decades earlier. The statistics involving race and incarceration are alarming. According to the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People, African American children represent 32% of children who are arrested in the U.S., 42% of children who are detained, and 52% of children whose cases are judicially waived to criminal court. African Americans and Hispanics make up approximately 32% of the population, yet in 2015, they comprised 56% of all incarcerated people. Why? Could it be that those in positions of power—law enforcement, district attorneys, politicians, judges, businessmen, and others—are predominately white and harbor an unwarranted prejudice and fear of people of color? Could it be that they judge a person not on the merits of a case, but their race and by extension, unchallenged biases fueled by the institution of white supremacy?

The stories of injustice and inequality are endless. The Washington Post reported that in 2016, 34% of the unarmed people killed by police were black males, a figure which is disproportionate to the number of African American males in the U.S. population. At the same time, police officers who are responsible for fatal shootings of unarmed black men rarely go to trial, if they are convicted of any crimes at all. According to research conducted by Philip Stinson, an associate professor of criminal justice at Bowling Green State University in Ohio, “Between 2005 and April 2017, 80 officers had been arrested on murder or manslaughter charges for on-duty shootings. During that 12-year span, 35% were convicted, while the rest were pending or not convicted.”

The judicial system seems no less biased against African Americans and other people of color. In 2011, Kelley Williams-Bolar, an African American mother, was convicted of falsifying her address to enroll her daughters in a better Ohio school district. The judge gave her to two concurrent five-year sentences, which he then suspended to 10 days. He cited his decision as a lesson to others who might consider jumping school district boundaries. She served nine days of that sentence. Felicity Huffman, a wealthy white actress, also wanted a better education for her daughter. She bribed a proctor to correct her daughter’s SAT test answers. In 2019, Huffman was sentenced to 14 days in federal prison, fined $30,000 and 250 hours of community service. Why the discrepancy in sentences? The crimes were both motivated by parents wanting a better education for their children. Could race or economic standing have been an issue?

Sometimes research can reveal motivations. I turn to as many different sources as possible when researching a book—newspaper articles, witness statements, trial transcripts, correspondence. The transcripts of the Scottsboro Boys’ trials illuminated the fact that the systematic racism they faced still exists today. The rush to judge black people more harshly than whites, to assume their guilt before weighing any facts can be summed up in one prosecuting attorney’s closing argument. “Don’t go out and quibble over the evidence,” he said. “Say to yourselves ‘we’re tired of this job and put it behind you. Get it done quick…’”

The past does not have to be prologue. We can do better. We can be better. I know this is true because I witness it every time I step into a school and see young people of every ethnicity, of every faith, and of every sexual identity working together. Perhaps these children can teach the adults around them about how acceptance, equality, and fairness should not be a privilege, but an unequivocal right.”

Larry Dane Brimner is the recipient of the 2018 Robert F. Sibert Award for the most distinguished informational book for children for his title Twelve Days in May: Freedom Ride 1961 (Calkins Creek/Boyds Mills & Kane). He is the author of more than 200 fiction and nonfiction books for children.