When people talk about film, the first word that comes to mind it’s Hollywood. But believe it or not, before the “H Town”, other cities in countries around the world where not just pioneering but taking this new media to boundaries that sometimes we now take for granted.

When people talk about film, the first word that comes to mind it’s Hollywood. But believe it or not, before the “H Town”, other cities in countries around the world where not just pioneering but taking this new media to boundaries that sometimes we now take for granted.

Argentina was one of the first. Cinema arrived in Argentina soon after being launched in Paris and, in a short time, the first national productions started to be shot. Among other attractions, there were world-class pioneers in scientific and animation movies. But the true industry started only in 1933, with the establishment of sound film.

The good times, when the Argentine movies were watched all over Hispanic-America, lasted until the early 1950s. Afterwards, the gradual closure of the big studios, the growth of television, the stagnation of popular cinema and the isolation of auteur cinema imposed other rules. On the basis of these new rules, present-day Argentina cinema has been reduced as to quantity and market, but it retains a special quality, which has been acknowledged worldwide.

The first filmic exhibition, with a picture of the Lumiére’s, took place on July 18, 1896. In 1894 the kinetoscope had already made its arrival and, by early 1896, a  kinetoscope concessionaire had tried public projections with a device of his own invention. In 1897, the import of French cameras started, and a Frenchman living in Argentina, Eugene Py, became the first filmmaker and cameraman with La bandera argentina (The Argentine Flag), a short movie.

kinetoscope concessionaire had tried public projections with a device of his own invention. In 1897, the import of French cameras started, and a Frenchman living in Argentina, Eugene Py, became the first filmmaker and cameraman with La bandera argentina (The Argentine Flag), a short movie.

In 1898, Dr. Alejandro Posadas initiated surgical cinema by shooting his own surgeries. In 1900, the first theaters specially intended for movie projections and the first filmed news reports appeared.

After that, it is worth mentioning the essays of sound film in 1907; the first fiction movie with professional actors, La revolución de mayo (May Revolution), in 1910; the first feature-length film, Amalia, in 1914; the first big success, Nobleza Gaucha (Gaucho Nobleness; with a cost of 25,000 pesos and box-office collections for half a million in six months, aside from bootleg copies) in 1915; the first animation feature-length movie in the world, El apóstol (The Apostle), in 1917; and the first woman director in Latin America, also in 1917.

Including melodramas, thrillers, comedies and movies with countryside subjects, during the silent film period over 200 movies were shot, the most outstanding ones being those with a tango climate by Agustín Ferreyra. However, a true industry was never organized and the films were never properly preserved.

The Argentine film industrial really advanced with sound films in 1933, the most popular being the film Tango. The program for the film is shown on the left, virtually at the same time, Argentina Sono Film was born, soon, these and other companies produced 30 films per year which they exported to Latin American countries.  By 1938 there were already 29 filming galleries, but the equipment used had not made the same advancements. The main filmmakers of the time were Moglia Barth, Francisco Mugica, Manuel Romero, Daniel Tinayre, Luis Saslavsky, de Savalía, Borcosque and Luis César Amadori with writers such as Mario Soffici and Leopoldo Torres Ríos.

By 1938 there were already 29 filming galleries, but the equipment used had not made the same advancements. The main filmmakers of the time were Moglia Barth, Francisco Mugica, Manuel Romero, Daniel Tinayre, Luis Saslavsky, de Savalía, Borcosque and Luis César Amadori with writers such as Mario Soffici and Leopoldo Torres Ríos.

In the 40’s, Carlos Hugo Christensen with dramas and erotic comedies and the epic cinema director Lucas Demare made their appearances.

There was increasing state intervention into the growing industry as well as the formation of the Associated Argentine Artists cooperative. Argentina stayed neutral during WWII which created a lack of outside films and influx of lower grade original films. Eventually, this led to forms of censorship, blacklists, discretionary distribution of original films and favorable treatment.

The main filmmakers were the prolific Moglia Barth. The more promising and skillful Manuel Romero with: La vida es un tango (Life is a Tango); La muchacha del circo (The Circus Girl) and Fuera de la ley (Outlaw), thriller forbidden in New York; among others). The rigorous Mario Soffici, the scri pt-writer of Prisioneros de la tierra (Prisoners of the Land) -according to surveys, the best Argentine movie-, of other social dramas and also some comedies; the suburban poet Leopoldo Torres Ríos author of La vuelta al nido (Back to the Nest), Pelota de trapo (Cloth Ball) and Aquello que amamos (What we love); the rhetoric but effective Luis César Amadori filmmaker of Dios se lo pague (God Reward You) and Almafuerte; and the creator of bourgeois comedies, Francisco Mugica in Así es la vida (Such is Life), Los martes, orquídeas (Tuesdays, Orchids). Also the more refined Daniel Tinayre, Luis Saslavsky, de Savalía and Borcosque.

Shortly afterwards, Carlos Hugo Christensen with dramas and erotic comedies with: Safo and El ángel desnudo (The Naked Angel), the comedy directors Bayón  Herrera and Schlieper, and the epic cinema director Lucas Demare with: La guerra gaucha (The Gaucho War) and Su mejor alumno (His Best Pupil) also made their appearances.

Herrera and Schlieper, and the epic cinema director Lucas Demare with: La guerra gaucha (The Gaucho War) and Su mejor alumno (His Best Pupil) also made their appearances.

Three key events in the 1940s were the formation of the Associated Argentine Artists cooperative, with a large part of the “intelligentzia” of the period; secondly, the crisis for the lack of virgin film (as a consequence of Argentine neutrality during the Second World War) and since 1944, the increasing state intervention.

The filmmakers that rose to prominence were: Leopoldo Torre Nilsson, Simon Feldman, Martínez Suárez, and René Mugica. At the same time, Fernando Birri ran his school of documentary cinema.

Between 1973 and 1975, with a democratic government and a considerably stable economy, Argentine cinema reached great reviews and box-office success, and even films nominated for the Oscar (Sergio Renán) and La Raulito (Murúa).

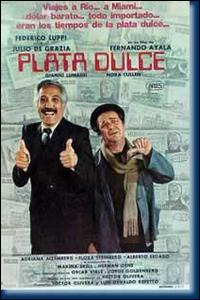

But censorship and a new military government put an end to this flourishing period. Recovery would come later, with Tiempo de revancha (Time for revenge, Adolfo Aristarain), Plata Dulce (Easy Money) , a satire, and the documentary called La República perdida (The Lost Republic, Miguel Pérez). In 1984, the government of the Radical Party did away with censorship and a filmmaker from the sixties, Manuel Antin, in charge of the INC, promoted the birth of a new generation, which came to be called Argentina Cinema in Freedom and Democracy.

However, the 1989 Argentine economic crisis, with flourishing inflation, turned into producer-directors depending on state subsidies or foreign co-productions.

Argentine filmmakers placed their hopes on the new Act, passed in 1995, forcing video and television to make financial contributions to Argentine movies. This is fueling young directors to produce a wider variety of films to try to reestablish the industry.

Researched by : Gustavo Guzman

Sources: The Argentine Film Council

Pablo C. Ducros Hicken Cinema Museum