First a word from our sponsor, Time:

First a word from our sponsor, Time:

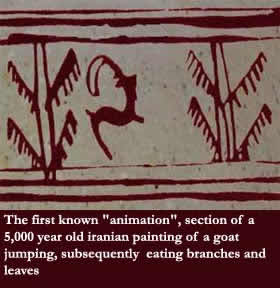

In every sense, filmmaking is all about time. Not just the time it takes to conceptualize, write, pitch, fund, produce and release a film, let alone the time it’s taken me to get this article to CWB…no, I mean Time in its most abstract state of self. There is no single definition for time that isn’t fuzzy and indefinite. Even the word “indefinite” seems to pop up in many of these definitions. A bit circular, really…but if we accept that events happen in the universe with or without us–that things are constantly changing from one state to another…then time in some way, is simiply our way of keeping track of the changing state of all things, whether we see them or not, in our universe. In this way, early man, keeping track of how many times the sun rose and set, or painting an image of a deer on a cave wall with berry juice, was recording slices of time.

keeping track of the changing state of all things, whether we see them or not, in our universe. In this way, early man, keeping track of how many times the sun rose and set, or painting an image of a deer on a cave wall with berry juice, was recording slices of time.

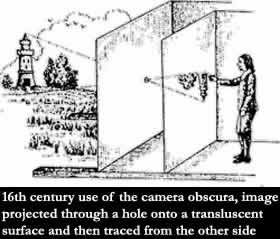

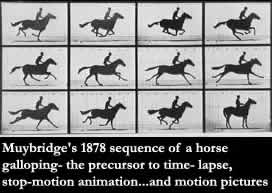

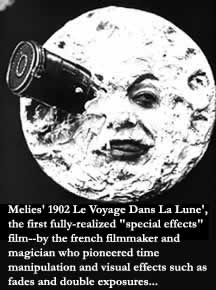

Then Time passed–in other words generations came and went, and events transpired that mankind learned from and built atop, and eventually we figured out how to use more advanced technology to record slices of Time. We created “photography” by coating a celluloid “film” with a silver compound and inventing mechanisms called a  “shutter” and an “aperture” with which to allow light to be regulated for focus, intensity and duration as it hits this film surface. With these tools we could record a transpiring event in much shorter duration of Time, and with greater artistic control. The results were amazing, because quickly moving subjects such as a running person, or a galloping horse could be “frozen” in a pose that the human eye never had been able to critically study before. Quickly, another incredible revelation was made: if you capture enough of these frozen moments in succession, you can play them back and fool the eye into thinking its watching the real-life event play out on a screen, and the first motion picture was born.

“shutter” and an “aperture” with which to allow light to be regulated for focus, intensity and duration as it hits this film surface. With these tools we could record a transpiring event in much shorter duration of Time, and with greater artistic control. The results were amazing, because quickly moving subjects such as a running person, or a galloping horse could be “frozen” in a pose that the human eye never had been able to critically study before. Quickly, another incredible revelation was made: if you capture enough of these frozen moments in succession, you can play them back and fool the eye into thinking its watching the real-life event play out on a screen, and the first motion picture was born.

Almost simultaneously it was realized that you can draw successive images and play them back, too!–in the margins of a book (as I did as a child), or on film—and animation was born. And that if you simply photograph still objects while you slightly manipulate their spatial relationships in each successive frame, when you play them back you get what we call “stop motion” (a curiously contradictory term!). And if you record widely-spaced, successive frames of natural

margins of a book (as I did as a child), or on film—and animation was born. And that if you simply photograph still objects while you slightly manipulate their spatial relationships in each successive frame, when you play them back you get what we call “stop motion” (a curiously contradictory term!). And if you record widely-spaced, successive frames of natural  scenes whose changes are are evident only on a much slower scale of Time, (such as clouds passing, or flowers blooming), you get “time lapse”. And if that wasn’t enough, it was also established that if you vary the rate of image capture (or your depiction of that rate in drawings), and/or the rate in which you play them back, you can create moving sequences that appear faster or slower than our perception of real time.

scenes whose changes are are evident only on a much slower scale of Time, (such as clouds passing, or flowers blooming), you get “time lapse”. And if that wasn’t enough, it was also established that if you vary the rate of image capture (or your depiction of that rate in drawings), and/or the rate in which you play them back, you can create moving sequences that appear faster or slower than our perception of real time.

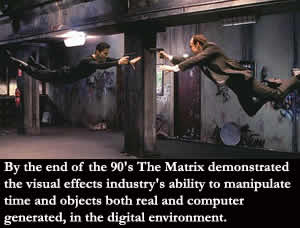

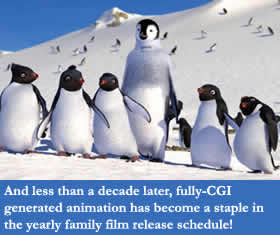

This bundle of discovery of temporal capture and manipulation happened in less than a hundred years, and has already been with us for over a hundred more. Add modern-day computing power, and it’s no wonder that today’s visual effects-driven and animated films such as The Matrix and Happy Feet (both of which I am proud to have played a critical role in) are such sophisticated, convincing entertainments.

proud to have played a critical role in) are such sophisticated, convincing entertainments.

In this digital age of cinema, by the time you get to view a film, it’s most likely that computers have touched it. There are microprocessors in every video camera, every modern television, even in modern-day film cameras. Whether capturing the image, post-producing it, distributing it and/or viewing it–there’s most likely a computer working in the chain, if not every step of it. And sooner rather  than later, as you must be aware, there will be no need for film. We are smack-dab in the middle of the digital revolution of film and communications, which of course is evidenced by the fact that you are reading this article served to you from a computer, and received by you on a computer.

than later, as you must be aware, there will be no need for film. We are smack-dab in the middle of the digital revolution of film and communications, which of course is evidenced by the fact that you are reading this article served to you from a computer, and received by you on a computer.

In the articles to come we will examine the continuing evolution of the incredible ways we are using computers and computer-aided tools to slice up the events that transpire in time which get manipulated and then get played back in every aspect of the visual storytelling form we call filmmaking. And in the time it’s taken you to read this introduction, things have evolved even further in this realm, one way or another. I guarantee it.

Next “Time”: Ultra-high speed cameras=ultra slow motion and a whole new way of looking at just about anything.