As the 2007 AFI FEST steps in its tenth day, a little girl in a head scarf will be filling the screen at the Arclight Theater in Hollywood, making mischief on the streets of Teheran as she becomes increasingly drawn to punk, Iron Maiden, and her love of self-expression.

As the 2007 AFI FEST steps in its tenth day, a little girl in a head scarf will be filling the screen at the Arclight Theater in Hollywood, making mischief on the streets of Teheran as she becomes increasingly drawn to punk, Iron Maiden, and her love of self-expression.

Her name is Marjane, and she represents Marjane Satrapi, who won the Cannes Jury Prize with PERSEPOLIS, her animated feature based on her four award-winning graphic novels, international best-sellers since they began appearing in France in 2000. In the film, Satrapi’s memoirs carry the voices of Catherine Deneuve, playing her mother, and the actress’s real-life daughter, Chiara Mastroianni, playing Marjane. Their talent and fame enhance Marjane Satrapi’s film and bring to it extra audience appeal at the festival.

international best-sellers since they began appearing in France in 2000. In the film, Satrapi’s memoirs carry the voices of Catherine Deneuve, playing her mother, and the actress’s real-life daughter, Chiara Mastroianni, playing Marjane. Their talent and fame enhance Marjane Satrapi’s film and bring to it extra audience appeal at the festival.

Persepolis is presented under the banner for France, being the product of two new studios in Paris, Pumpkin 3D and Bibo Productions, where over 80 people worked on the film including Satrapi’s French collaborator, co-writer/director Vincent Paronnaud. While Hengameh Panahi of Celluloid Dreams is handling international sales of this French-language film, an English version is planned for release by the end of 2007 by Sony Pictures Classics in which American indie icon Gena Rowlands will replace the legendary French actress Danielle Darrieux for the voice of the grandmother.

In France, since November of 2000, the sales of the printed graphic memoirs Persepolis 1 and Persepolis 2 (published by L’Association) and Persepolis 3 and Persepolis 4 (serialized in the newspaper Libération) have exceeded 400,000 copies; worldwide, over a million have been sold. These publications have already been translated into over 20 languages. In the U.S. (published in English by Pantheon at Random House) the books are on the syllabi of over 160 high schools and universities as of last fall. In bookstores, it’s not the literature or art or comic book sections that display them, but the shelves for books on politics.

In France, since November of 2000, the sales of the printed graphic memoirs Persepolis 1 and Persepolis 2 (published by L’Association) and Persepolis 3 and Persepolis 4 (serialized in the newspaper Libération) have exceeded 400,000 copies; worldwide, over a million have been sold. These publications have already been translated into over 20 languages. In the U.S. (published in English by Pantheon at Random House) the books are on the syllabi of over 160 high schools and universities as of last fall. In bookstores, it’s not the literature or art or comic book sections that display them, but the shelves for books on politics.

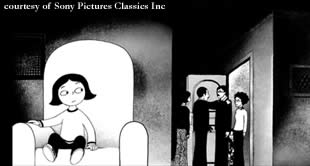

While Satrapi’s comic-book language can captivate anyone and little Marjane’s quips and coups may be universal in coming of age, these tales add a new dimension to graphic arts, whether in print or in cinematographic forms, through the author’s very pointed and personal perspective on the history of Iran. In Marjane’s child’s-eye view, the streets loom large with both immediacy and imagination. Men in suits line the city pavement, black marketeers muttering the names of contraband music they sell from their inner coat pockets. These prompt the girl, waist-high to them, to bargain stubbornly with her bold naiveté. Another frame shows her whirling like a dervish to a punk song, playing air guitar on a tennis racket in her bedroom. It’s a form that fits the context.

in coming of age, these tales add a new dimension to graphic arts, whether in print or in cinematographic forms, through the author’s very pointed and personal perspective on the history of Iran. In Marjane’s child’s-eye view, the streets loom large with both immediacy and imagination. Men in suits line the city pavement, black marketeers muttering the names of contraband music they sell from their inner coat pockets. These prompt the girl, waist-high to them, to bargain stubbornly with her bold naiveté. Another frame shows her whirling like a dervish to a punk song, playing air guitar on a tennis racket in her bedroom. It’s a form that fits the context.

Like other young heroines of graphic novels, comic books, and animé films, Marjane’s spirit carries her head-over-heels into adventure, but Satrapi’s images speak the shattering experience of seeing the overthrow of the Shah, the Islamic revolution, the political imprisonment of her uncle, and Iran’s war with Iraq. She wrestles with the repression in the city, because at home she’s taught to speak her mind and act on it. As the only child of Marxist parents, the girl attends the Lycée Français in Teheran until they send their outspoken daughter to Vienna at age 14 — as they see it, for her own protection.

Like other young heroines of graphic novels, comic books, and animé films, Marjane’s spirit carries her head-over-heels into adventure, but Satrapi’s images speak the shattering experience of seeing the overthrow of the Shah, the Islamic revolution, the political imprisonment of her uncle, and Iran’s war with Iraq. She wrestles with the repression in the city, because at home she’s taught to speak her mind and act on it. As the only child of Marxist parents, the girl attends the Lycée Français in Teheran until they send their outspoken daughter to Vienna at age 14 — as they see it, for her own protection.

But life as a teenage exile brings little comfort, and Marjane experiences a special kind of homesickness in Austria where she is branded with the religious fundamentalism and extremist values she left her own country to escape. The rest of the film is a testing of waters, with a return to Iran to reunite with her family, to enter art school, to marry, but also to question her future and to make the choices that will allow her to become the artist that she is today.

When Marjane Satrapi went to France in 1994, first to Strasbourg and then to Paris, having completed her university studies she found herself with a cohort of artist friends who shared a studio. These friends did her a special favor by introducing her to the work of graphic novelist Art Speigelman (Maus). She was also influenced by the French comic-book artist David B. Soon enough she achieved her own style, a bold black-and-white graphic resembling woodcut prints that, in its naïve, expressionistic form of simple shapes, forceful designs, and sharp contrasts, paradoxically embodies meanings more complex than the stereotyping reportage of international news media.

artist friends who shared a studio. These friends did her a special favor by introducing her to the work of graphic novelist Art Speigelman (Maus). She was also influenced by the French comic-book artist David B. Soon enough she achieved her own style, a bold black-and-white graphic resembling woodcut prints that, in its naïve, expressionistic form of simple shapes, forceful designs, and sharp contrasts, paradoxically embodies meanings more complex than the stereotyping reportage of international news media.

Her play between realism and iconic abstraction, with a text and subtext that can spar with each other, results in her own visual vocabulary. The peculiar ways she uses time, action, subject, and scene to provide multiple aspects of a place, a mood, or an idea all reveal her own grammar of the page. Yet how she translates her comic-strip transitions and closures into the editing strategies of an animation film, availing herself to the magic and mystery of non-sequitors in her portrayal of a very real world, will keep our eyes fixed on the screen as we follow her work in cinema.

Her play between realism and iconic abstraction, with a text and subtext that can spar with each other, results in her own visual vocabulary. The peculiar ways she uses time, action, subject, and scene to provide multiple aspects of a place, a mood, or an idea all reveal her own grammar of the page. Yet how she translates her comic-strip transitions and closures into the editing strategies of an animation film, availing herself to the magic and mystery of non-sequitors in her portrayal of a very real world, will keep our eyes fixed on the screen as we follow her work in cinema.

Whether serialized in newspapers or published in graphic novels or animated for the big screen, Satrapi’s self-portraiture is a unique way of writing that corresponds with her own political, personal, direct life experience. Building on a form of expression that has come to be known as “autographix” — a new combination of autobiography, history, and illustration — she continues to explore languages for storytelling today, whether they be trans-cultural (as in Persepolis) or feminist (as in Embroideries, 2003, which probes the lives of various women of her mother’s generation) or reflective of childhood (as in several books she wrote and drew for children since 2000). Even in her comics and commentaries for periodicals such as the New York Times and The New Yorker magazine, Satrapi is precocious, intelligent, and engaging with her visual and verbal wit.

self-portraiture is a unique way of writing that corresponds with her own political, personal, direct life experience. Building on a form of expression that has come to be known as “autographix” — a new combination of autobiography, history, and illustration — she continues to explore languages for storytelling today, whether they be trans-cultural (as in Persepolis) or feminist (as in Embroideries, 2003, which probes the lives of various women of her mother’s generation) or reflective of childhood (as in several books she wrote and drew for children since 2000). Even in her comics and commentaries for periodicals such as the New York Times and The New Yorker magazine, Satrapi is precocious, intelligent, and engaging with her visual and verbal wit.

Born in 1969 in the city of Rasht, in the Guilan region of Iran near the Caspian Sea, she describes herself as a mix of national ancestries and religious heritages — somewhat Azeri, Turkmen, Muslim, and Zoroastrian — but calls herself simply “Iranian.” Advocating peace instead of war, so that the money spent on arms can be invested in scholarships for youths to study abroad, Marjane Satrapi believes that living in a variety of countries and experiencing them first-hand is what helped her to understand the world and embrace other people. “Little by little, you can solve problems in the basement of a country, not on the surface,” she has pointed out. Satrapi shines a light in those dark corners. By taking us from the street to the page to the screen, Persepolis is bound to illuminate the spaces we share.