“Trust Me!” he roared. I glanced briefly down to check my footing. I had driven the entire day through sweltering desert heat with several large, full gas canisters filled to the brim jostling in the back of my little Citroen 2cv truckette. We were in the midst of the seventies oil crisis and could only buy gas on odd or even days depending on the last number of our license plates. But I was twenty-something, and nothing was going to stop me from driving to some house, somewhere in Cave Creek, Arizona where I would wait alone for hours in a strange garage for this moment—the moment when I would lay my eyes on Orson Welles. His production manager, Frank Marshall, called me upstairs, thrust a sun gun in my hand and sweetly barked, “Stand over there,” where I found myself suddenly and entirely under Welles’s command. My only choice was to obey.

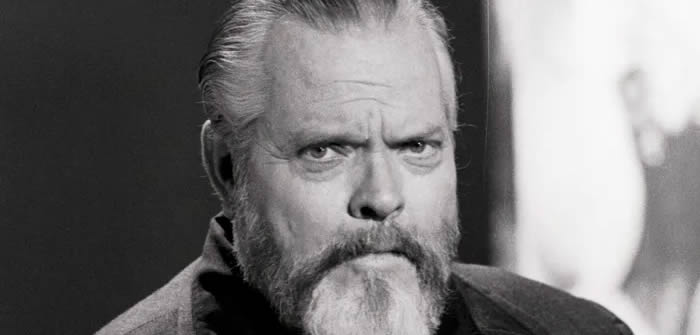

He was a vortex, an energy field surrounded by people, all kinds of people, futilely attempting to fulfill his every command. He stood in the center, handsome, compelling, and impeccably dressed from head to toe in a custom-made black cotton summer suit from Spain. His leonine head was framed by a magnificent, silver mane and beard, and at the center, the nucleus, was a great and beautiful eye. “Trust me!” he ordered with a voice that still echoes through my bones. So I did.

Many people have written about this creative giant: reviewers, critics and film theorists galore. I am none of these. I am an artist, a mother, a student of human nature and a filmmaker. So when my then-boyfriend, Bill Weaver (who later became my husband), was hired as a camera operator under DP Gary Graver on Orson’s last film, The Other Side of the Wind, I jumped at the chance to join him on location.

nature and a filmmaker. So when my then-boyfriend, Bill Weaver (who later became my husband), was hired as a camera operator under DP Gary Graver on Orson’s last film, The Other Side of the Wind, I jumped at the chance to join him on location.

By this time, I had worked in live action for several years and was no longer star-struck. I certainly did not expect what lay in the months ahead, however. The expression “Check your ego at the door,” took on new meaning, as I could only watch from the sidelines as the cast and crew appeared and disappeared in their flurry of production. Then it was my turn. My claim to fame? In order to justify my presence on the set, I got to be a background extra—until the day I was banished without explanation. I didn’t know what I had done, or if I had done anything at all. “Cut” he roared, “Get that lady out of here!” Devastated I stumbled out and ran through the darkness to my car, sobbing the entire 22 miles back to my hotel room, where I wallowed under the covers for another two days. I decided to go back, though, and thankfully, my return was tolerated by the titan.

My courage was rewarded with truly wonderful experiences. I watched Orson pull a performance out of Susan Strasberg by making her, yes making her, take off her boots to reveal what she was hiding: mis-matched stockings with runs in them. Her subsequent feat of acting was perfectly beautiful. I remember trying to sit as close as I dared to hear his wonderful stories, and I remember his great laugh when the production manager sent me, little timid me, alone out onto the staging area where Orson had prepared the entire set for dozens of extras to make a grand entrance. I also remember his sheer glee when things were actually going the way he wanted them to, and when he was operating the camera. And the moment he told me his first name was George and that if he could do it all over again, he would stay a painter (a beautiful book he wrote and illustrated for his daughter has since been published). I also recall him cutting Strasberg some  serious slack when her dog was hit by a car and killed; he loved animals. There is even a story in his authorized biography by Barbara Leaming about how he nursed a sick chicken back to health in his hotel room.

serious slack when her dog was hit by a car and killed; he loved animals. There is even a story in his authorized biography by Barbara Leaming about how he nursed a sick chicken back to health in his hotel room.

Down-time, too, proved rewarding. I sat on the edge of a bathtub, the only available free space on the set at the moment, with John Huston for hours talking about moviemaking (he advised me to write if I wanted to direct). And I got to know a young German distributor by the name of Jorgen. He told me there were another dozen or so of Orson’s films in various stages of completion stored away in a vault somewhere. Wouldn’t it be wonderful if someone like Oja Kodar, Orson’s trusted friend and companion could assemble this footage for posterity?

And I’ll never forget being thrust into a group of world class actors and having my one and only filmed acting experience directed by Orson Welles. I was so terrified I couldn’t hear his direction when a voice, his voice entered my head and said “That’s your ego, now drop it!” which I did through some mysterious mystical occurrence that took me to another level of awareness. I was actually functioning in the scene, brief as it was. Sadly, The Other Side of the Wind has not been released, and it appears the world will not have the enjoyment of this great man’s final work (and I will never know whether I made the cut!).

Though my path only briefly crossed his, I was forever impressed by Welles’s courage and kind, magnanimous heart. He really was “some kind of a man.”

Trending

- Shahab Hosseini in Pietro Malegori’s Shukran

- Karlovy Vary Film Festival winners

- Future of diversity, discussed at Karlovy Vary

- Palestine Islands wins 2024 Bridging the Borders Award at Palm Springs Shortfest

- Shadow of the Cypress from Iran wins at 2024 Tribeca

- The Count of Monte Cristo, review

- Bridging the Borders Award Jury and Nominees, 2024 Palm Springs Shortfest

- You Burn Me, review