The Berlin International Film Festival has presented frequent Homage programmes for outstanding protagonists in the world of film since 1982. The last Homage honoured American director Arthur Penn in 2007. Within the framework of its 58th edition, the Berlin International Film Festival is once again dedicating a showcase to an extraordinary personality in international cinema: the renowned Italian director Francesco Rosi. In his work, Rosi has critically reflected on political, economic and intellectual developments in Italy. Within the scope of the Homage, Francesco Rosi will receive the Golden Bear for Lifetime Achievement on February 14, 2008.

The Berlin International Film Festival has presented frequent Homage programmes for outstanding protagonists in the world of film since 1982. The last Homage honoured American director Arthur Penn in 2007. Within the framework of its 58th edition, the Berlin International Film Festival is once again dedicating a showcase to an extraordinary personality in international cinema: the renowned Italian director Francesco Rosi. In his work, Rosi has critically reflected on political, economic and intellectual developments in Italy. Within the scope of the Homage, Francesco Rosi will receive the Golden Bear for Lifetime Achievement on February 14, 2008.

“With their explosive power, Rosi’s films are still persuasive today. His works are classics of politically engaged cinema,” comments Berlinale Director Dieter Kosslick on the Homage.

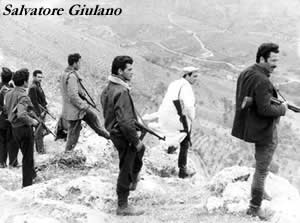

Francesco Rosi, who is now 85, has helped shape 50 years of Italian film history. The Berlinale Homage will present a selection of 13 films documenting Rosi’s oeuvre over the decades. With the film Salvatore Giuliano (1961/62), he first found his own personal style and established himself internationally: the film won the Silver Bear for Best Director at the Berlinale in 1962 and will be screened at the Honorary Golden Bear award ceremony on February 14, 2008.

will be screened at the Honorary Golden Bear award ceremony on February 14, 2008.

When Francesco Rosi made his directorial debut with La sfida (The Challenge) in 1958, he had already had years of experience as assistant director and screenwriter for several filmmakers, including Visconti. Neorealism defined his use of original locations and non-professional actors. In I magliari (1959, The Magliari) he drafted a realistic picture of rivalling Italian cloth salesmen in Hamburg, who were trying to make a place for themselves in the affluent West German society. In Salvatore Giuliano, Il caso Mattei (1971/72, The Mattei Affair, which won the Palme d’Or in Cannes) and Lucky Luciano (1972/73), he explored how economic and political power structures were intertwined with the Mafia. Set in his hometown of Naples, he exposed hushed-up building scandals in Le mani sulla città (1963, Hands Over the City), for which he received the Golden Lion in Venice. In the late 1970s, Francesco Rosi broke new ground, both aesthetically and thematically. In Cristo si è fermato a Eboli (1978/79, Christ Stopped at Eboli) and Tre fratelli (1980/81 Three Brothers), Rosi turned his attention to the inner lives of his characters. These films also mirrored the conflicts between Italy’s rich north and its poorer agricultural south – the latter presented in the archaically poetic landscape of Lucania in Cristo si è fermato a Eboli.

Francesco Rosi made his films with both Italian and international stars, including Gian Maria Volonté, Alain Cuny, Philippe Noiret, Rod Steiger and John Turturro. Rosi was also at all times responsible for the screenplays of his films – which he usually co-authored with a team of several writers; in addition, he did the research for his investigative films. On a number of films he collaborated with screenwriter Suso Cecchi d’Amico as well as with Raffaele la Capria and Tonino Guerra.

Francesco Rosi made his films with both Italian and international stars, including Gian Maria Volonté, Alain Cuny, Philippe Noiret, Rod Steiger and John Turturro. Rosi was also at all times responsible for the screenplays of his films – which he usually co-authored with a team of several writers; in addition, he did the research for his investigative films. On a number of films he collaborated with screenwriter Suso Cecchi d’Amico as well as with Raffaele la Capria and Tonino Guerra.

Francesco Rosi’s films never fail to display great commitment and passion and still have an enormous impact today – a fact that underscores their greatness as works of art,” remarks Dr. Rainer Rother, Artistic Director of the Deutsche Kinemathek – Museum für Film und Fernsehen, which is responsible for the Homage.

Many of Rosi’s films on highly topical issues in recent Italian and European history have sparked fierce public debates. In his cinematic (re-) construction of authentic cases, he lays out the evidence and in so doing adds a historical dimension to events.