Some filmmakers do not make films. They write love letters. The camera is their pen and the celluloid, their sheet of clean white ironed paper. Their central emotion so ensconced in the maddening love of a young lad for his lovely, their feeling so absorbed in attachment, their sentiment so soaked in deep affection, and their ardor so strong, that the articulation of the sentences in the letter stops being a bother, and words take you over with the strength of their obsessive passion.

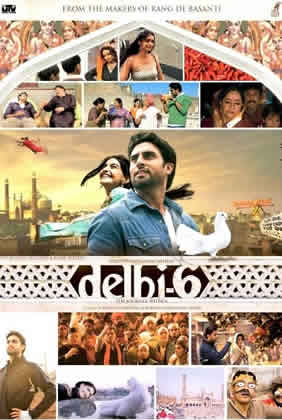

Rakesh Omprakash Mehra, the much famed director of the eccentric, content-in-its-own isolation, and on-the-verge-of-a-tempest film, Rang De Basanti, loves Delhi 6, an area identified by the digit suffixed at the end of its pincode. And he, with the vehemence and obstinacy of the young lad in love, decides to make the first half of his latest film, Delhi 6, a love letter to the region.

The structure is incoherent, there is hardly any discernible plot, the vignettes work as episodes, and the pieces scatter here and there with the lunacy of a bottle of marbles emptied on the floor. And yet, who cares about the articulation, when the sentiment is so overwhelming? Somehow, he manages to travel at breakneck speed, moving from America to Chandi Chowk, to a discourse on the classical notion of divide between the simplicity of India and the cynicism of America, to a description of the usual generation gap, to a superfluous love angle, to a small topical elaboration on the average middle-class dream. And yet, somehow, which the reviewer can only attempt to fathom, each of the presentation of every individual part is rather conventional. The sum of the parts is something completely singular, and I daresay, fantastic. It is, as I said, the sentiment that makes it all work.

singular, and I daresay, fantastic. It is, as I said, the sentiment that makes it all work.

Mehra might be presenting the most orthodox notions of describing a generation gap, such as showing the simultaneous fascination and astonishment of a foreigner, at the warmth of a familial structure (a family other than the family), and his grandmother’s seemingly alien concepts of preparing for her own death, but he does it with such conviction, that you are bound to fall for it. After all, what is ‘I love you’, if not the most abused sentence in the world, and yet, said with conviction, it works.

Mehra imports his foreigner who discovers an alien land character from Rang De Basanti, and lets his emotions towards what he experiences, drive the film, thus, in the process, letting us, the viewers, become both participants in his discovery of a land which we know too well, and of people discovering him. Most of the humour in the film, thus, is similar to how when you when you notice a foreigner’s surprise at elements you are only too familiar with, being amused by his reaction to the object of his surprise; which is in this case: corrupt police officers, religious customs, and the caste divide. In its essence, this device of using a foreigner’s reaction to the object, and not the object itself as the central element, reverses our general scorn at those objects, and makes them more palatable.

The first half, at its bare minimum, is about characters, a lot of them, wonderfully written, all given distinctive traits and some hilarious lines. Mehra is more fascinated by a kaleidoscopic, encompassing view of the location rather than centering on only certain elements, and is thus, like a love letter is, which is not able to focus on one thing and has so many things to say; scattered and spread over a wide variety of characters, and their concerns. It is surprising, how Mehra constantly travels on the edge, goes here and there, eventually going nowhere, and yet, never falls over.

The first half, at its bare minimum, is about characters, a lot of them, wonderfully written, all given distinctive traits and some hilarious lines. Mehra is more fascinated by a kaleidoscopic, encompassing view of the location rather than centering on only certain elements, and is thus, like a love letter is, which is not able to focus on one thing and has so many things to say; scattered and spread over a wide variety of characters, and their concerns. It is surprising, how Mehra constantly travels on the edge, goes here and there, eventually going nowhere, and yet, never falls over.

He just has to have the most unique style in the industry now, barring none. While Bannerjee is the most inspired, and Bhardwaj the most polished, Mehra’s style cannot be categorized at all, really, since he, and his cinematographer Binod Pradhan, show such disdain for all the conventionalities like the rule of thirds, or the diagonals, and just pick up the steadicam, become a tourist and follow whoever they want to in Chandni Chowk, thus encompassing entire the length and breadth of the region, and making just about everyone their guide, or just rapidly cutting between different shots, imitating the verve and fervor of the Nouvelle Vague, but constantly using the qualities so unique to the location to remain firmly grounded and being irreverent without being experimental, which is not the need of this film.

But like Mehra’s sophomoric effort, beneath the revelry, and beyond the joyousness, lies a certain simmering under tonal disturbance; which is in this film, the concept of division – walls between brothers, thin tent fabrics between castes, and an inevitable ideological division between the co-existing religious parties. There is a speculation in the chilly Delhi winter about a ‘kaala bandar’(black monkey), or the monkey-man, would later determine both the downfall, and the enunciation of the central point of the film. There is also a Ram Leela, which leaders interrupt in the middle of the show, and as he lays emphasis on the symbolic, monolithic battle between Rama and Ravana, you can anticipate the direction the film will take in the second half, but you pray it does not. Like all love letters, the letters are enamoring only till the time they are love letters.

When they become expressions of laborious concerns that the beloved reader is not concerned with, they become boring. Your prayers are not answered, as Mehra wakes up with a revelation that so counters his impudent assurance in the first half, and makes him again settle in the false promises of a ‘plot’, wherein a film has to make a point, have a central theme, and preach a message. And at the exact moment at which it attempts to reinvigorate the possibilities of a ‘plot’ in the technical sense, it loses it in the literal one.

There is a certain sense of misfortune in the manner in which Mehra lets the possibility of a great film slip off his hand, as he suffocates the possibility of beautiful ambiguity, and as he reduces the mystical figure of the ‘kaala  bandar’(black monkey), which could have stood, at the same time, for so many different things, to one of the most overused symbols in Indian film history, and as he chooses to convert his trip down the memory lane to a trip to prove a point, you believe that the entire first half headed into only one certain direction, thus matching the huge disappointment of beginning to wonder about the intention of the panoramic photograph of the region, and turning it over to find why it was taken in the first place, a why that did not need to be appended.

bandar’(black monkey), which could have stood, at the same time, for so many different things, to one of the most overused symbols in Indian film history, and as he chooses to convert his trip down the memory lane to a trip to prove a point, you believe that the entire first half headed into only one certain direction, thus matching the huge disappointment of beginning to wonder about the intention of the panoramic photograph of the region, and turning it over to find why it was taken in the first place, a why that did not need to be appended.

Threads, which till now, flew in their glorious sense of freedom and isolation like the eponymous pigeon of the Masakalli track, now begin tying into the most ridiculous, and most loose of all knots. The Ram Leela becomes an obvious symbol of the battle between good and bad, the till-now peacefully co-existing religious sects turn on each other as a wonderfully crafted introductory scene featuring a sadhu who appends each judgment with an interrogatory ‘Ok?’, becomes the trigger for what is by now such an obvious trivilialised account of riot; that you slap your head in disgust at your own prior belief against your anticipation, hoping against hope that he would not follow down the much-too tread path, and create a concoction as unique as the first half. He doesn’t ofcourse.

There is something about Mehra’s second halves. He just cannot help but become more and more bizarre in his sudden love for convention as the film moves towards a closure, as if insecure about the capability of his own film, that he often falls for what is the easiest and the shortest route to a conclusion, such as in Rang De Basanti or even in Aks. The problem here is the film did not need a conclusive statement as such. It is almost as if Mehra writes his first halves with a sense of such quality, which makes him so eager to consummate the writing on the screen, that he writes a hurried second half.

There is something about Mehra’s second halves. He just cannot help but become more and more bizarre in his sudden love for convention as the film moves towards a closure, as if insecure about the capability of his own film, that he often falls for what is the easiest and the shortest route to a conclusion, such as in Rang De Basanti or even in Aks. The problem here is the film did not need a conclusive statement as such. It is almost as if Mehra writes his first halves with a sense of such quality, which makes him so eager to consummate the writing on the screen, that he writes a hurried second half.

The second half thus, becomes a series of rushed, much too anxious to preach, eager to reach a definite goal, or become means towards reaching that end, conversations between the religious groups, which are mostly staged completely like theatre plays with large ensemble casts on screen, where one character comes to the fore and says a dialogue and fades into the darkness, and the second comes and resumes the chain. And as the hatred grows, the by-now disgusted NRI takes it upon himself to become either the source of, or atleast the preacher of basic notions of brotherhood, tolerance, and the notion of God being in all of us.

The point is, with a film which takes itself so lightly in the first half, such a heavy-handed approach in the second, wherein Mehra not only attempts to hammer his point home but hammer such widely spoken points home; works in reverse for the film, where instead of believing in him; you just cannot believe him. As a result, the film becomes a more extended PSA, rather than a love letter it could have been, and you stand there, in dismay, at the possibility of ‘what could have…’

It is a love letter, but the bottom half got smudged by ink.