Susan Morgan Cooper, director of An Unlikely Weapon, was born in a tiny village in Wales, where her parents put on plays to raise money for charity. Susan came to America as an actress, scoring a small role in a Clint Eastwood movie. She soon discovered however, that film editing excited her much more than acting. When she met a young Croatian girl displaced by the Balkan War, Susan felt compelled to make her first documentary Mirjana, One Girl’s Journey. A project Susan is developing with Fairplay Pictures centers around the street children of Rio and the Death Squads that routinely murder them. Eight years ago, Susan made a film about a remarkable cop in East Los Angeles, who turned around the lives of a group of gang kids, grooming them into a winning roller hockey team. Now Susan is set to direct the feature film based on their story.

Bijan Tehrani: What was your motivation in making of An Unlikely Weapon?

Susan Morgan Cooper: I have always been fascinated by war photographers; how they go into war zones and lay down their lives to give us the story. My first narrative film was a thirty minute short called “Stringers”, and it was about a tormented photographer in Vietnam. For my character’s work I had used the photos of Eddie Adams. I never would have dreamed that years later I would be making a documentary about Eddie.

BT: When did you actually start work on the project?

SMC: I started in 2004. I was sitting home on a Saturday night like a major loser, and the phone rang and it was a friend of mine, Armando, who owns an Italian restaurant down the road. He said, ‘Susan, there is a woman here who wants to make a documentary’, and that was Cindy Lou Adkins, Eddie Adams’ sister-in-law, and she became my co-producer on the film. We hit if off, and I flew to New York to meet with Eddie.

BT: Did you shoot all of the interviews in the film?

SMC: All of the interviews in the film I shot, with the exception of Eddie. I met with Eddie, and we talked and talked, and sat together and cried over a documentary film that he made about a young boy with progeria, a disease that makes him age rapidly. This little boy of ten looked like an old man. We sat together watching the film and both sobbed, and we knew immediately that we had a bond. I had flown to Italy to work on a movie, and was there for a few months, and while I was there I got the news that Eddie had been diagnosed with Lou Gehrig’s disease. During those months he became dreadfully ill and died. I had decided that I did not want to film him while he was sick, because I didn’t want to diminish that enormous presence that I knew. I was devastated, because I had given him my word that I would make the movie, but I did not want to make a distant documentary, but now that my subject was dead, I didn’t have a clue how I would capture Eddie’s presence on screen.

BT: I was really impressed with Adams’ work; I had seen his photography before, but through this film it was like I was seeing it in a new light. What was your approach in structuring this film?

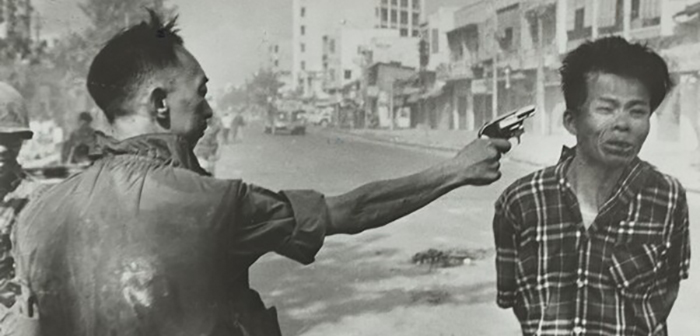

SMC: For me, making a documentary is like panning for gold. You put your hands down in the river bed and pick up a bunch of mud in your hand, and sift and sift, and finally you find a speck of gold. And you do it again, and slowly you string these pieces of gold together. I try not to have a definitive plan; I think it was John Lennon who said that ‘Life is what happens when you are busy making other plans.’ I tried to let the movie speak to me from the footage. Yes, I definitively knew that his Pulitzer photograph, and the way it haunted him, would be a big part of the film. But I didn’t quite know how I was going to take everyone on a journey through the rest of his work. That came through discovery.

BT: Eddie’s famous picture is brought up in a very interesting way. For me it was like a modern version of tale of Greek mythology.

SMC: Ah! That is so smart that you say that. That is so true.

BT: How much do you think Eddie helped in changing people’s ideas about different issues, like war?

SMC: First of all, a few months ago the BBC radio called me, and they asked if I would go on the air as Eddie Adams’ voice. They were having a world debate about whether or not we should broadcast death. And there is, of course, Eddie’s iconic image in which a Saigon police chief is shooting a Viet Cong prisoner point blank in the head. The bullet was still lodged in the victim’s head at the moment of the photograph. I said to them that, “Yes, a photographer could intervene and save someone’s life. But by taking a photograph, Eddie Adams had saved thousands of lives, because that photograph helped bring the end of the Vietnam War. Subsequently, when the Vietnamese refugees were trying to leave Vietnam, they would just pile on these rickety boats, and they were getting lost at sea, plundered and raped. One day, Eddie ran down to the sea and jumped aboard one of these boats. There were 50 people on this boat, out at sea with no shade. He had no idea what he was going to do, but he stayed. He took a series of photographs called “The Boat of No Smiles”. Eddie said that he had been in refugee camps all over the world, and had photographed 13 wars, and whenever he would point a camera at a child, they would smile. And he said that none of the children on this boat smiled. Well, up until his photographs, America would not allow any Vietnamese refugees into the country. After his photos were presented to Congress, President Carter changed the ruling, and because of Eddie Adams, 250,000 Vietnamese were allowed into the United States.

Vietnamese refugees were trying to leave Vietnam, they would just pile on these rickety boats, and they were getting lost at sea, plundered and raped. One day, Eddie ran down to the sea and jumped aboard one of these boats. There were 50 people on this boat, out at sea with no shade. He had no idea what he was going to do, but he stayed. He took a series of photographs called “The Boat of No Smiles”. Eddie said that he had been in refugee camps all over the world, and had photographed 13 wars, and whenever he would point a camera at a child, they would smile. And he said that none of the children on this boat smiled. Well, up until his photographs, America would not allow any Vietnamese refugees into the country. After his photos were presented to Congress, President Carter changed the ruling, and because of Eddie Adams, 250,000 Vietnamese were allowed into the United States.

BT: That’s really amazing. How long did it take for you to shoot the whole film and have it ready for editing?

SMC: Ready for editing? Well, it didn’t quite work that way. If I had Eddie to work with, I probably would have spent a few days just sitting with Eddie and talking to him until he and I were both exhausted. Then I would have made a narrative thread through the film. But not having him, I had to rely on the voices of others to tell the story. I started off with an interview that Hal Buell from the AP  gave to me. It was from some years ago, but it only took me to a certain level. I needed to know more and dig deeper. So, I went to people like Tom Brokaw, Morley Safer, Bob Schieffer, Bill Eppridge, and David Kennerly. I interviewed them because they had been there with Eddie in Vietnam. They could fill in the blanks in telling his story. I began to build the structure slowly as I went along.

gave to me. It was from some years ago, but it only took me to a certain level. I needed to know more and dig deeper. So, I went to people like Tom Brokaw, Morley Safer, Bob Schieffer, Bill Eppridge, and David Kennerly. I interviewed them because they had been there with Eddie in Vietnam. They could fill in the blanks in telling his story. I began to build the structure slowly as I went along.

BT: Has this been shown to anyone from Vietnam?

SMC: No. I think that would probably be a wonderful thing to do. Nick Ut (who took the picture of the Napalm Girl) and I have become very close since this movie. He has talked about going over to Vietnam, possibly sometime this year. And I told him that I would love to go with him and show the film in Vietnam.

BT: Has the film had its theatrical release in any U.S theaters?

SMC: Not yet. It was chosen by the International Documentary Association to play for an event called Docuweek, which is a qualifying process for the Academy Awards. I was thrilled that they chose my film. It played for a week at the ArcLight in Los Angeles, and a week in the Village East Cinema in New York. Those are the only two showings it has had so far. But it opens at the Quad Cinema in New York on April 10th.

BT: Will it have a larger release in Los Angeles?

SMC: Yes. I have had so much interest from theater owners; from Boston to Santa Fe. So, absolutely yes. I have a consultant who told me not to open in three theaters at once, but to open in New York, get my reviews, take my time with it, and then open in another city.

BT: It is a very beautiful film, and I wish you luck with it. What is your next project?

SMC: I am working on a movie called “Road Runners”. This is based on a documentary I made ten years ago. It is about a policeman from East LA who takes a group of kids out of a gang and turns them into a successful roller hockey team. It is not a Disney movie; it is a lot grittier than that, but it has such heart. Ten years ago when I made the documentary, I promised these kids that one day I would make a real movie, and now I have the financing for it, and will make it this year.

BT: That sounds like a very interesting project.

SMC: Do you know that probably the high point in my career so far happened a few weeks ago, when Rob Reiner of Castle Rock called me up and wanted to tell me personally how much he loved my movie. He said how he was very moved by it, and how he could identify with Eddie’s dilemma as an artist, feeling that your work is never good enough.

BT: Your film is not actually a biographical film really. It is a lot more about the soul of an artist, and not just the story of his life. It is very successful. Sometimes these types of films have educational value, and sometimes they stand by themselves as an artistic film. But I think yours does both of these things very well.

SMC: Thank you. I want to also say that The Associated Press is throwing me a big screening in New York on April 14th, and one of the White House press photographers has contacted me, and said that, ‘Once Obama is settled in office, we want to bring you out and have a screening.’, which is really wonderful!