Some of my favorites foreign films submitted didn’t make the shortlist; here are reviews of eight of the nine short listed nominees. “Kelin“, the entry from Kazakhstan was not available for review by press date.

Some of my favorites foreign films submitted didn’t make the shortlist; here are reviews of eight of the nine short listed nominees. “Kelin“, the entry from Kazakhstan was not available for review by press date.In alphabetical order:

Argentina‘s entry, Juan Jose Campanella’s stylish genre-bending thriller “The Secret In Their Eyes” (El secreto de sus ojos) is a non-stop, witty, entertainment. Campanella (who shot episodes of Argentina’s “Law and Order”) adapted Eduardo Sacheri’s novel “La pregunta de sus ojos“, working with Sacheri. Director-editor Campanella blends romance, psychological back-stories, crime procedurals and comedy in a fluid complex suspensor.

Retired criminal-court employee Benjamin Esposito (Ricardo Darin) is writing a novel based on an unsolved murder-rape. He tells Judge Irene Hastings (Soledad Villamil), who is wary of lending her support. Morales (Pablo Rago), husband of the murdered woman, spent years haunting the train stations watching for the murderer. Two immigrant workers were railroaded for the murder, as flashbacks to the 70’s show. The flashbacks stir the political subtext and explain Irene’s initial reluctance to help Benjamin.

“Eye’s talk” claims Benjamin, decoding the small eye movements that betray peoples’ secret. It’s a useful quality for a novelist, an investigator and a lover. Irene and Benjamin have been attracted to each other since the 80’s when she joined the department. But Benjamin is out classed, pining for the Cornell-educated beauty married to a well -connected politico. Irene’s drawn in to helping him, as they argue about the power of memory, the major topic of a country with a buried ugly past. Playing Benjamin over a twenty-year span, Darin allows the frustrations of years of working in a corrupt system leak out of every pore. Javier Godino plays the assassin working for the secret police’s death squad. Comic Guillermo Francella is memorable as Benjamin’s alcoholic buddy Pablo Sandoval. (On my 10 Best List)

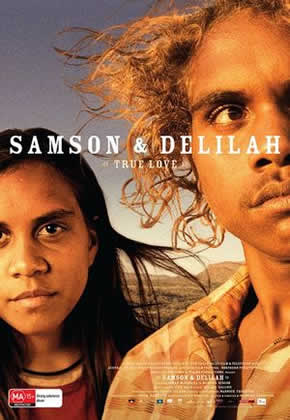

Australia‘s entry “Samson and Delilah” is a first time feature by aboriginal writer-director-cinematographer Warwick Thornton. It won the Caméra d’Or at Cannes.

Set in a small isolated Warlpiri community in the Central Australian desert, it’s the love story of two teens, Samson and Delilah, living on the fringe of a society that has tried to make them disappear. With no job, no school, no other young people, the frustrated characters depend on rituals to fill their time. Thornton establishes the rituals, then changes them slightly as they repeat day after day. The simple narrative, their Walkabout through the urban society, which has tossed them away, is told in these subtle changes.

Austere, in the family of Bresson (though less spiritual), and flashed with bleak deadpan humor, it is virtually a silent film. Teenage Samson (Rowan McNamara) and Delilah (Marissa Gibson), the only kids we see in this forgotten desert town, communicate by hand gestures, looks, and silent actions. The music, which is an important thread in the story, is either a rock cassette on an old boom box, a Mexican pop song (by Ana Gabriel) played on a car cassette deck, or the annoying, dulsatory chords of Samson’s brother’s Reggae band.

Every day, 15 year-old ginger-haired Samson wakes to Charlie Pride’s “Sunshiny Day”. He reaches for his tin of petrol to sniff (it cuts his hunger) pulls on his one shirt and walks onto the porch, where his big brother’s listless band practices the same Ska song over and over. Like an angry kid longing to belong, Samson grabs the guitar and plays some rock riffs before brother (Matthew Gibson) snatches it back with a clout to his head.

Every day, Delilah feeds her grandmother Nana ( Mitjili Napanangka Gibson) her meds, pushes her wheelchair to the mobile clinic, and the tin chapel, prepares her paints and helps her finish the elaborate songline paintings they sell to a local dealer for $200 a pop. At night, she climbs into the community car and listens to Mexican love songs. One night, drifting away to her tape, she sees Samson on his porch. Plugging his boom box into his brother’s amp, he begins to gyrate, topless, to some rock and roll, exuding the sexual charisma of a young McQueen or Ledger. To her, he’s dancing to the bolero she hears in her headphones. He’s made an impact.

Everyday, Samson follows her to the one room store, past the sole pay phone which rings and rings, but no-one answers.

One day, he scribbles “S 4 D –Only Ones” on the wall, to get her attention. She buys him a snack. That’s all the encouragement he needs. He follows her home; she tosses rocks to drive him off. He packs up his thin mattress and tosses it over her fence. She throws it back. Sitting on her painting, Nana chuckles, “Your husband, he’s the right skin for you.” This annoys Delilah, but Samson’s marked his turf. Dragging his mattress close to them, he blissfully watches them paint. He traps and kills a kangaroo to feed his new family. Cocky, he parades past his brother’s house who yells in vain “Bring that kangaroo back, I’m your brother. I’m hungry.” It’s nice that the sound is subjective; His brother’s voice is in the background. In a Hollywood film, they’d mix the dialogue louder, closer, to make sure we got the point

When Nana dies in her sleep, Delilah mourns, chopping off her hair with a knife, and burns Nana’s painting. Her female relatives beat her ritually, blaming her for letting her grandmother die. Samson exiles himself. Picking a violent fight with his brother he’s clubbed by him. A neighbor woman drives him off. From the hill overlooking the town, he watches the commotion, Delilah’s relatives the ambulance.

He carries the sleeping, battered Delilah to the stolen community car, and takes off for the big city (Alice Springs), where they fetch up under a bridge, in the temp camp of road veteran Gonzo. Gonzo (played by Thornton’s brother Scott) intones Tom Waits’s “Jesus Gonna Be Here”, adding a harsh comic relief. Watching them sniff petrol he cautions, “You wanna cut that shit out; it’ll fuck up your brain”, says alky Gonzo swigging from his flask. A victim of the Australian’s systemic negligence portrayed in the film, Scott dried out in rehab in order to shoot the film. Unable to get a word out of the vacant eyed kids, who’ve both retreated into a drug sniffing haze, paternal Gonzo finally gets Samson to stutter his name.

Like Mother Courage, terrible things happen to Delilah, mostly missed by Samson in his petrol sniffing haze. Following him, she’s bundled into a car by thugs. This and the later accident are handled like bleak vaudeville, sudden Mr. Bill jokes in the background. When Delilah makes it back to camp, no comment, she joins him in his sniffing world. It’s tribal. Thornton passes no judgment.

Delilah discovers that galleries sell Nana’s painting to tourists for thousands of dollars. Stealing supplies, she paints her own dot painting and tries to sell it. A gallery owner doesn’t even turn to acknowledge her. A waitress drives her off from a cafe, like she’s herding an animal. It’s the genius of Thornton’s strategy that we identify with Delilah, not the unresponsive Australians whites. We move in her dream, see Alice Springs through her eyes, not the other way around.

Later, in an astonishing scene, as the two of them walk through town, she’s run over. When she doesn’t return, drugged, passive Samson chops his own hair off. Thornton’s sudden scenes of violence overwhelm, set against the film’s entrancing stillness. The sound design adds to the film’s hypnotic charm. Under the bridge the constant whooshing and thumps of tires replaces the sounds of their village.

Meditating on his steady close-ups of Samson, we suddenly realized that time has passed. We assume Delilah’s dead.

But caretaker Delilah isn’t through with him. She arrives, bundles him into a car and takes him to her people’s abandoned distant house. Leg in a cast, she drags a tree back to build a fire. She kills a roo, hauls him to a well and bathes him. Once she’s made their home, she starts to paint again. As Charlie Pride sings “All I Have To Offer Is Me” on Samson’s boom box, they smile, they’re home, back of the beyond.

To film their first feature, based on Thornton’s experiences growing up, Thornton and producer Kath Shelper found a deserted town off the grid, home to a tin missionary Church (seen in the film) which had been restored as a historic landmark. They brought electricity and dressed the bare town with every can, rotted car and piece of rubbish you see on screen. They interacted with the non-actors to create an organic community, a realism that the skeletal crew wouldn’t disturb. Thornton, a confident cinematographer, designed wide shots, often allowing his young actors to walk into frame and towards the camera. Mitjili Napanangka Gibson is actually a painter and Marissa’s grandmother.

To film their first feature, based on Thornton’s experiences growing up, Thornton and producer Kath Shelper found a deserted town off the grid, home to a tin missionary Church (seen in the film) which had been restored as a historic landmark. They brought electricity and dressed the bare town with every can, rotted car and piece of rubbish you see on screen. They interacted with the non-actors to create an organic community, a realism that the skeletal crew wouldn’t disturb. Thornton, a confident cinematographer, designed wide shots, often allowing his young actors to walk into frame and towards the camera. Mitjili Napanangka Gibson is actually a painter and Marissa’s grandmother.

While never mentioning it, “Samson and Delilah” is a cinematic rebuke to the media propaganda issued by the Rudd government to expand the nightmarish Northern Territory “intervention” of 2007 which evacuated indigenous communities, forcing hundreds into overcrowded camps, and seded control of aboriginal land to mining and agro-business.

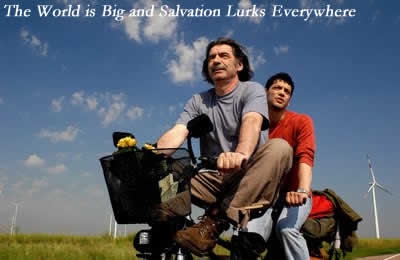

Bulgaria‘s entry Stephan Komandarev’s “The World is Big and Salvation Lurks Everywhere” is part sentimental road movie about recovered roots, part a mediation on emigration. Based on a novel by liya Troyanov who immigrated from Bulgaria to Germany (like his protagonist) it’s a model of new European filmmaking, filmed in 4 countries with investors from Bulgarian, German and Slovenian investors and a Serbian cast.

Alexander (Carlo Ljubek) is born in the 70’s, (as we see in a delivery room sequence) to a family of backgammon masters. His grandfather Bai Dan (Miki Manojlovic of Kusterica fame) is the greatest of them all. Believing that backgammon is a metaphor for the Game of Life, Bai Dan claims that their home town is the secret center of world backgammon.

During the darkest years of the Communist regime, Bai Dan made backgammon sets in a secret basement workshop, until he was discovered by the authorities and arrested, but not before he presented a beautiful handmade board to Alex (‘Saschko’) who he’s groomed to supplant him as the greatest backgammon player on earth.

Pressured to inform on his father, Alex’s dad ‘Vasko’ (Hristo Mutafchiev) flees to West Germany with wife Yana (Ana Papadopulu) and son Alex. Their dream of a western paradise is replaced by the drear Italian detention camp, where they spend years eating spaghetti and waiting to make a new life.

We learn this in flashbacks. The film begins with a car crash, which kills Alex’s parents on their first visit home to the new Bulgaria. Grown Alex, suffering amnesia, lies in a hospital bed. Stubborn granddad Bai Dan rushes to Leipzig. With peasant logic he determines to bring Alex home to regain his memory, traditions and backgammon skills.

All of this is revealed in flashback. The film begins with a car crash, which kills Alex’s parents on their first visit home to the new Bulgaria. Grown Alex, suffering amnesia, lies in a hospital bed. His grandfather rushes to Leipzig. With peasant logic, he’s determined to bring  Alex home to regain his memory, traditions and his backgammon skills.

Alex home to regain his memory, traditions and his backgammon skills.

Crafty gramps has his way. Listless Alex finds himself on a tandem bike journey across the Alps and Balkans to his hometown. Along the way they visit the Italian asylum detention camp, where a figure from Alex’s past, the one cocky camp resident determined to move to the US, still lives. Unable to adapt, he stayed on, even after the camp closed. Like a prisoner afraid to leave the shelter of prison, this poor fellow can longer imagine the freedom of the outside world.

At a vacation camp, virile Bai Dan jump-starts Alex’s love life, and he spends a romantic night with lovely Baba Sladka (Lyudmila Cheshmedzhieva). Thawed by their musical, drunken journey (not quite as picaresque as it should be) Alex recovers his memory and mystical chops. Backgammon Saschko is reborn.

I’m resistant to these sorts of sentimental memory plays. Giuseppe Tornatore leaves me unaffected, as does this Balkan Paradiso, but the film seems to be an audience pleaser. It’s energized, well cast and has an upbeat score.

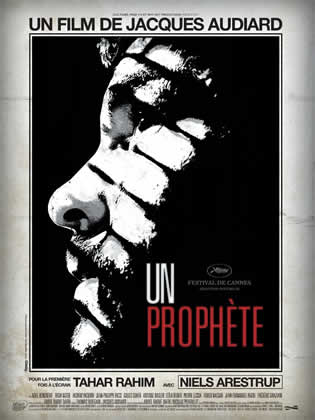

France’s entry Jacques Audiard’s “A Prophet” is a tough prison coming of age film. Son of director-screen writer Michel Audiard, Jacques Audiard won the César for best first film for his road movie “See How They Fall” (Regarde les hommes tomber, 1994). He won three Césars for “Read My Lips” (Sur mes lèvres, 2001) and eight Césars for “The Beat That My Heart Skipped” (De battre mon cœur s’est arrêté, 2005). A Prophet (Un prophète) vaults him to International center stage.

Known for embracing and elevating genre material, Audiard tent poles his complex film with a central relationship of searing intensity. Unknown lead Tahar Rahim is harrowing as Malik el Djebena, the shy young man who painstakingly recreates himself in the image of his father figure Luciani. Audiard’s close ups mine every frown, every blink, every fleeting anxious expression to create sympathy for the character who brutally kills a prison friend as a necessary rite of passage. Niels Arestrup (“The Beat That My Heart Skipped“) is white hot as Malik’s reluctant tutor, Corsican capo Cesar Luciani, who controls the prison. In one scene Arestrup milks the character’s fragile health to deliver a scene of ferocious threat.

Abdel Raouf Dafri’s script is one of a handful of French films to feature a Muslim hero (Adel Kechiche “La graine et le mulet” is another). Malik’s an Arab role model, a man with no options or education, who uses his life in prison to make himself a successful man, albeit a crime lord. Audiard’s cynical “Pilgrims Progress” subverts tropes of Warner’s thirties prison pictures, detailing the elaborate corruption of prison life, a smooth running market place in which everyone and everything’s for sale, from the lowliest inmate to the prison officials.

Using freeze frames, intertitles, and recurrent visions, Audiard creates a dark ascension complete with ‘forty day and forty nights’ in solitary.

Like the “Go to Jail” card in Monopoly, Malik uses his six-year incarceration to build a lucrative crime empire.

Put in a cell block with religious Muslims (who reject him) and the Corsicans, non-religious Malik finds himself in a no-mans land, a world in which the Corsicans try to maintain control, outnumbered by the “bearded ones.” Recruited by Luciani, he’s ordered to kill a kindly, disciplined Arab prisoner, Reyeb (Hichem Yacoubi) or be killed himself. The remarkable murder scene replays in Malik’s head as he refashions himself.

Maliks’s absorbed into the Corsican gang as a glorified slave, mocked and despised. Bit by bit, hungry Malik becomes indispensable to Luciani.

Malik learns to read, picks up Corsican and the workings of Luciani’s business. Put in place as a “passe-partout” gopher by Luciani, he navigates the different prison subcultures, each with their own code of honor. Running Luciani’s errands on day leaves from the prison, (including the murder of the Corsican’s rival), Malik sets up his own business on the outside, using his released prison buddy, Ryad, Jordi the Gypsy (Reda Kateb), and the Muslim brotherhood, whose favor he now assiduously courts.

Adel Bencherif is compelling as Ryad, the cancer-ridden family man who needs to set something aside for his young family (Malik inherits them).

Alexandre Desplat’s brilliant unobtrusive score bridges Audiard’s stylistic jumps. Stephane Fontaine’s vivid handheld camerawork, Juliette Welfling’s surgical editing, and a stark grey production design by Michel Barthelemy add texture to the riveting novelistic 155-minute story.

Alexandre Desplat’s brilliant unobtrusive score bridges Audiard’s stylistic jumps. Stephane Fontaine’s vivid handheld camerawork, Juliette Welfling’s surgical editing, and a stark grey production design by Michel Barthelemy add texture to the riveting novelistic 155-minute story.

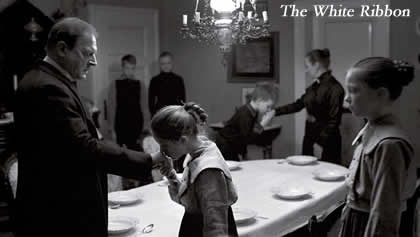

Germany‘s entry Michael Haneke’s “The White Ribbon.” won the Palme d’or at Cannes. This faux “whodunit” is not my favorite Haneke. Taking a page from Alice Miller’s analysis of toxic, repressive German pedagogy, Haneke explores the possible roots of fascism in his grim ” German Children’s Story”, beautifully shot in black & white by Christian Berger (“Cache”, “The Pianist“). Inflected by early Bergman, Berger’s images on drained color stock won the ASC, NSCF, NYFCC and LAFCA awards.

It’s as if Kathe Kolwitz had illustrated “Children Of The Damned.” Haneke’s precise, leisurely black and white images grant a Brechtian distance to this dark fable set in the Protestant village of Eichwald. Everyone owes fealty to the landowner, the Baron (Ulrich Tukur), his aggrieved wife (Ursina Lardi), and the rigid pastor (Burghart Klaussner).

It’s a way of life, which will abruptly end with the assassination of Archduke Ferdinand of Austria in Sarajevo.

The only moments of warmth are the fumbling courtship of shy, young Eva (Leonie Benesch) and her older suitor, the schoolteacher (Christian Friedel).

The white ribbon (which summons ideas of feudalism) is given to young women as a symbol of purity. In this town, it’s awarded to children who’ve strayed but are trying to improve. They have no role models.

Deadening patriarchy, child abuse, torture and premature death are the norm. Even the children are vile, save for the pastor’s long-suffering young son who offers his own pet bird as a replacement of his father’s slain canary. The deadened eyes of the children (heir to their fathers’ sins) reflect the coming half-century of ruthless war.

Israel‘s entry “Ajami” (co-directed by two young directors, Israeli-Jew Yaron Shani and Israeli-Arab Scandar Copti) is set in the eponymous Jewish-Arab-Christian neighborhood in Jaffa. It’s another in a long series of International films using gangster tropes to uncover social injustice (with a de rigueur tragic ending.)

With the exception of Stephen Gaghan’s intelligent, content rich “Syriana“,

I’m largely resistant to interwoven films. “Ajami” interweaves five chapters. The choice to play them out of sequence complicates the story unnecessarily. Boaz Yehonatan Yacov’s dark hand-held camera work doesn’t help clarify a story that confused many in my screening audience.

In a fast paced opening, a young boy is gunned down in front of his house by mistake, setting off a bloody clan feud. Young Malek works illegally to pay for his mother’s operation. A wealthy Palestinian  wants to marry his Jewish sweetie and is taunted by his friends. A Christian restaurateur blocks his daughter’s marriage to an Arab. A Jewish cop searches for his missing soldier brother.

wants to marry his Jewish sweetie and is taunted by his friends. A Christian restaurateur blocks his daughter’s marriage to an Arab. A Jewish cop searches for his missing soldier brother.

Non-pros workshopped for 10 months and improvised swathes of the action. As some scenes were shot in the street, confused neighbors jumped into the action, not realizing it was a film shoot. In my favorite scene a Jew from Jaffa tries to get his lounging Arab neighbors to remove their sheep, they’re keeping him up, he can’t get a good night’s sleep. Another strong scene is the expensive life and death deal brokered by an Imam to end the inter-clan feud.

The Netherlands entry, Martin Koolhoven’s exquisite “Winter In Wartime,” is based on the popular children book by Jan Terlouw. Artfully bridging a boy’s adventure story, with the harsh truths of World War II, tracks the wartime loss of innocence of 14-year-old Michiel, an unlikely hero.

Michiel (Martijn Lakemeie), son of the mayor of a small town near Zwolle, hungers for adventure. From his bedroom window, Michiel spies an RAF plane going down in flames. Michiel and neighbor Theo search the wreckage, recovering a stopped watch. Spotted by a Nazi patrol, they escape, but everyone recognizes the Mayor’s son. When Michiel and his father (Raymond Thiry), are called before the local Nazi Commander Auer (Dan van Husen), the only color relieving Koolhoven’s icy grey palette, is the red of the Nazi flags and Michiel’s ruddy cheeks. (Koolhoven never uses warm tones till Armistice as people celebrate in the street.)

Theo’s older brother Dirk (Mees Peijnenburg), a resistance member, asks Michiel to deliver a letter to the village blacksmith Bertus, in case he doesn’t make it back by morning. The raid is betrayed, Dirk is arrested and Bertus is shot by the Germans in front of Michiel, whose father manages to free Dirk’s father, joking with the Nazi’s who’ve come to arrest him.

Michiel misunderstands the patient compromises his father makes to protect those around him. In Michiel’s eyes he’s a coward, schmoozing the Nazi High Command. He lionizes his mother’s brother, charismatic Uncle Ben (Yorick van Wageningen), the family resistance fighter. Whenever he visits it’s a house party.

Michiel’s itching to get into the Resistance fight despite Uncle Ben’s warning ” if you get mixed up in this, I’ll chop your head off.” Opening the letter Michiel finds a map leading him to a cave where British pilot Jack (Jamie Campbell Bower) is hiding. Jack expects Bertus or Dirk, but it’s up to Michiel to bring Jack to a contact in Zwolle. Jack learns to rely on Michiel who brings him food, and his sister Erika (Melody Klaver). As Michiel and nurse Erika tromp through the woods, they’re spotted by suspicious neighbors and Nazi patrols.

Koolhoen captures the queasy feeling of occupation, everyone is suspicious of everyone, even eye contact is suspect. When Dirk is arrested, and later his own father, Michiel assumes it’s sneaky Schafter (Ad van Kempen), but neighbor Schafter has his own reasons to fear detection. Assuming responsibility for Jack, Michiel shies from even telling Ben anything, but finally he gives Ben a fateful message to deliver to England.

Nothing is simple in this moral tale. When Michiel falls through the ice, the one who risks the ice to haul him out is a Nazi soldier, as townspeople watch idly from the bank. A shaving scene between Michiel and his father brings them closer together. Thiry creates a subtle portrait of a practical man of resolute goodness, whose heroism Michiel understands too late.

The war turns Michiel into a man. In the shifting boundary between good and evil during wartime, he makes tough decisions. Seeking the hidden flyer, the Nazi arrest and execute locals. Attempting to save his father, Michiel realizes he would betray Jack if it would help.

The film never loses momentum. Relationships are drawn with great emotional resonance. Anneke Blok (as Michiel’s mother) has a powerful scene when she tries to visit her imprisoned husband. Jack and Erika become a wartime couple.

Shooting exteriors in Lithuania, Koolhoven recreates the famous snowbound “Hunger Winter” of 1945, using real, plastic and digital snow, used to stunning effect in a chase on horseback.

Pino Donnagio’s score, featuring a boy soprano, recurrent themes for Michiel and his father, and rich operatic moments, recalls the lyric scores of classic Italian films. Floris Vos’s subtle period settings, Guido van Gennep’s artful widescreen landscapes and judicious handheld camera work, Job ter Burg’s unobtrusive editing and Pino Donaggio’s dynamic score make for a seamless, classic package.

Peru‘s entry Claudiia Llosa’s “The Milk of Sorrow“, won Berlin’s “Golden Bear.”

In a riveting opening sequence, dying Perpetua stares into the camera, singing a list of atrocities she and her family suffered at the hands of Peru’s “Shining Path”, when she was raped and forced to swallow her tortured husband’s castrated penis. Perpetua’s legacy of fear is passed on to daughter Fausta (Magaly Solier), one of the offspring suckled on “the illness of the milk of sorrow”. To pay for her mother’s funeral, Fausta works for a rich patrona in Lima. She wears a potato in her vagina as a safeguard from rape. It takes root and sickens her, as a clinic docter discovers. Fausta befriends the gentle gardener Noé (Efraín Solis). Fausta’s manipulative employer pianist, Aida (Susi Sanchez) trades pearls for Fausta’s songs, as she begins to find a voice. Natasha Braier’s controlled compositions add grace to this allegorical piece. Llosa treats her inflammatory material with great restraint, using folk magic and Andean superstition to uncover the deep roots and horror of neocolonialism.