If François Truffaut’s “The 400 Blows” launched The Nouvelle Vague, “Breathless” was the salvo over the bow that was heard around the world. (Chabrol’s “Le Beau Serge” (1958) was little known outside of France.)

If François Truffaut’s “The 400 Blows” launched The Nouvelle Vague, “Breathless” was the salvo over the bow that was heard around the world. (Chabrol’s “Le Beau Serge” (1958) was little known outside of France.)

Critics of the magazine Cahiers du cinéma, turned filmmakers, reconstructed Hollywood genre films through the lens of Italian neo-realism. Their young casts, jazzy black and white hand-held location shots (in natural light), experimental editing, voice over narrative style, mixed in Godard’s case with slogans and visual cultural quotes imbedded in the image, redefined Cinema for their generation. Hollywood’s young quake, culminating in the golden age of Hollywood auteur films of the 70’s, was a response to their cultural, political and esthetic critique.

Rejecting classical literature as sources, these cineastes loved French or American Pulp writers. “Breathless” was the first pulp homage.

Needing to edit the film, Godard trimmed his long takes using jump cuts. This device became his signature. Breaking with the smooth seductive editing of the Studio system, which catered to illusion, Godard’s rapid change of scene and improvised quality, suddenly made Cinema with a capitol C look old hat. He shifts from screwball to noir, from neo-realism to melodrama. Characters “break  character” and speak directly to the camera. Over and over Godard calls attention to the fact that we are watching a film, a series of images.

character” and speak directly to the camera. Over and over Godard calls attention to the fact that we are watching a film, a series of images.

Involving the audience, making us self conscious and aware of the process of film making, was his radical departure. His devices, seen as insulting to the audience by mainstream critics of the day, inform every form of visual and sound media today. Before cynicism entered the scene, before post -modern irony, The Nouvelle Vague believed in the power of cinema to change things and made an international generation believe in it too. Ironically its strategy of formal deconstruction is now the material of advertising and decades of smug post-modern media works

The film’s crew is a Cahier’s graduating class. Godard wrote the script from a story by François Truffaut. Claude Chabrol was the technical advisor. Filmmaker Jean-Pierre Melville plays writer Parvulesco. Godard plays an informer. Soon to be director Philippe de Broca plays an uncredited journalist, International cinema éminence grise Pierre Rissient was the assistant director. In what is now known as “guerilla-filmmaking style, Godard’s small team roamed Paris, shooting without permits. They put Coutard and camera in a wheel chair to avoid paying for dolly tracks. They used available light. Actors repeated last minute dialogue fed to them by the nightly scripting Godard, since everything would be dubbed later on.

Rialtos’ re-release celebrates the 50th anniversary of “Breathless” with a gorgeous black-and-white 35mm print from a restored negative supervised by original DP Raoul Coutard and featuring new subtitles by Lenny Borger.

Godard’s homage to American gangsters features a seductive, showboating Jean-Paul Belmondo as Michel Poiccard, a naive, existentialism -spouting car thief who fancies himself a bad guy (arguable cinema’s first copy-cay gangster.) Media and reality, modified by media is Godard’s subject. The opening shot show the back page of a newspaper with Michel hidden behind it reading the paper. His manhunt is detailed in newspaper stories. Michel  knows himself, invents himself, through and for the newspaper.

knows himself, invents himself, through and for the newspaper.

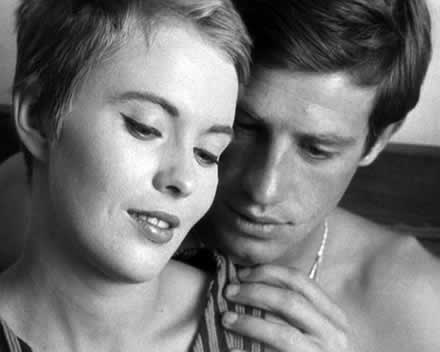

Michel impulsively killed a cop, surprising himself. Fleeing to Paris, with the police in pursuit, he meets his femme fatale. Aping Bogart, the seductive, misogynist Michel mugs and flourishes his way through his romancing of un-impressed Patricia Franchini (Jean Seberg) the tee-shirt wearing American who sells The New York Herald Tribune in the street. After a few nights together, he invites her to go on the lam to Rome. She turns him in.

Belmondo and Seberg still fascinate as the insouciant pair of lover. They play act characters that haunt their and our film memory. He’s a loner; of course he comes to a bad end. She’s the cool, self-protective femme fatale. We watch their decisive bad actions, and somehow don’t blame them. We want to be them. (The film rescued Seberg’s reputation after her disastrous “Joan Of Arc” and launched Belmondo’s stardom.) Self reflective, (literally) in a modern way, the pair check themselves out in store windows and mirror, assessing themselves, playacting. That was new too.

A generation of American girls donned ballet slippers, striped sailor shirts and pixie cuts hoping to snag their own Belmondo. Before feminism, Patricia was sexually liberated, intellectual and intuitive and, unlike the clinging, self-effacing heroines of earlier films, a fast learner who adapted to a hard-boiled game while we watched. She decides when or if they’ll sleep together, she’s the one who  catalogues her past lovers.

catalogues her past lovers.

The scene in Patricia’s apartment, where they survey art, books and music, is an unexpected tour de force. Like birds in a mating display of flamboyant plummage, their personalities peeked through a flourish of pop references (the first such scene in film that I can remember) as they argue about where to hang a poster or quote their favorite authors. They use a bidet, gasp! They make love tented by sheets. It’s still an amazing sequence.

Godard explores restlessness and love versus freedom. Michel wants to settle down with Patricia. She interested because he’s on the lam. Their provisional tragedy is punctuated with youthful philosophical remarks. “I don’t want to be in love with you, that’s why I called the police,” explains Patricia. ” I stayed with you to make sure I was in love with you…or that I wasn’t.” replies Michel, whose melancholy nostalgie de la boue finally plays out when he’s gunned down in the street.

Pierre Melville’s improvised monologue as an opinionated novelist at a press conference is one of the glories of the film. Patricia wants to be taken seriously as a novelist, but like all pre-feminist women, the men around her think about her looks first. When she interviews Melville, he wants to flirt. ‘What’s your greatest ambition” she asks. His answer “to become immortal, then die” prefigures Michel’s tragic end. A mysteriously wonderful close-up of the musing Patrica and its slow dissolve punctuate his oracular remark.

Master DP Coutard’s shots of Seberg’s cool profile are, well, breathless. His exquisite close-ups influence many cinematographers. Strolling or driving around with the pair, Paris, in summer, has never looked more, spontaneous. Restless walking or driving scenes make Paris seem the youngest, freshest city in the world. Their are aerial shots of Notre Dame and the city, set to Martial Solal’s swinging noir themes. The street lamps lit up as if directed (they were.) We visit the Melvillian cafes and cheap neighborhood hotels, which will become familiar in later Nouvelle Vague films.