Born in 1932, Canadian prodigy Gould began public performance at 14. His provocative 1955 recording of Bach’s Goldberg Variations (Columbia Records) made him famous worldwide. He was just 23.

Born in 1932, Canadian prodigy Gould began public performance at 14. His provocative 1955 recording of Bach’s Goldberg Variations (Columbia Records) made him famous worldwide. He was just 23.

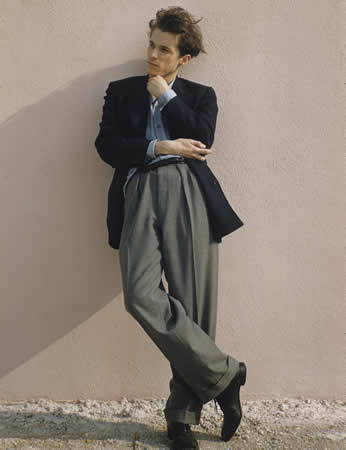

As we see and hear in this carefully constructed portrait by Michèle Hozer & Peter Raymont, Gould’s older parents made the handsome child pianist the center of their focus.

The flamboyant virtuoso that crafted his persona as carefully as his performances, had a matinee-idol glamour that is fully exploited in this thoughtfully assembled portrait. Like Bruce Webber’s “Let’s Get Lost” (about Chet Baker), archival footage and press photos from the 50’s capture the legendary cool of New York of the day. Pictures of the young pianist with “rock-star” status are reminiscent of the iconic B&W; photos of Actor Studio luminaries.

During the 24-year-old Gould’s world-famous Russian tour in 1957, he played sold out houses and received five minute long standing ovations. In Leningrad they sold out 1,300 seats, added seats to the stage, and sold 1100 standing room only tickets.

His 1962 New York Philharmonic concert is also highlighted. Leonard Bernstein famously introduced Gould with the qualifying remarks “You are about to hear a rather, shall I say, unorthodox  performance of the Brahms D Minor Concerto, a performance distinctly different from any I’ve ever heard, or dreamt of for that matter…But the age-old question still remains: ‘In a concerto, who is the boss, the soloist or the conductor?” We “can all learn something from this extraordinary artist, who is a thinking performer.”

performance of the Brahms D Minor Concerto, a performance distinctly different from any I’ve ever heard, or dreamt of for that matter…But the age-old question still remains: ‘In a concerto, who is the boss, the soloist or the conductor?” We “can all learn something from this extraordinary artist, who is a thinking performer.”

Known for his baritone humming, heard in all of his recordings, recent speculations cite Gould as a sufferer of Asperger’s syndrome (a currently chic diagnosis) though the film avoids this topic.

Tired of the “bullfighter” aspect of public performance, Gould retired at 31 to Lake Simcoe in Ontario, where he devoted himself to recording. I wish the films had explored Gould’s composing, and his recordings of Strauss, Mozart, Brahms and Beethoven and the modern atonal masters Schoenberg and Berg and Hindemith.

He developed acute hypochondria, constantly taking his blood pressure. His diet of anti-depressants heightened his reclusive paranoia, which led to his breakup with Cornelia Foss.

After retiring from public performing, Gould continued to give interviews. Happily the film uses much of this material laced with his brilliant oddball charm. His incisive thoughts on the culture (disseminated in his writings and Radio, TV productions) are giving their due by Ms. Hozer and Mr. Raymont, who consider him “one of the most important artists of the 20th century.” Unseen footage and bites from studio and home recordings give the film an organic soundtrack.

There have been other films about the reclusive prodigy, notably the François Girard’s beautiful “32 Short Films About Glenn Gould” (1993) and “Glenn Gould: On the Record/Off the Record” but none have penetrated protective Gould’s love life, nor captured the qualities of his early life. Interviews with two women in his life, close friends and Gould scholars ponder his enigmatic contradictions. Childhood pal John P. L. Roberts, Russian conductor Vladimir Ashkenazy, and even pop-singer Petula Clark weigh in.

Cornelia Foss, who left composer-conductor Lukas Foss, bringing her two children to live with Gould, discusses their four and a half years together and the paranoia that sundered their relationship. “Anything  pretentious made him ill,” she explained. Her children describe a man who was good with children and had an important impact on their lives. Gould later lived with Hungarian soprano Roxolana Roslak, also interviewed.

pretentious made him ill,” she explained. Her children describe a man who was good with children and had an important impact on their lives. Gould later lived with Hungarian soprano Roxolana Roslak, also interviewed.

Gould’s intense style is instantly recognizable, cerebral yet muscular with balanced attack. Gould re-recorded the Goldberg Variations in 1982. (His last recording.) He died at fifty of the complications from a stroke.

The iconoclast, who described himself as “the last puritan”, was a bridge between cultures. His dedication to the recording process, where he could perfect his performance with edits from various takes, predicted the current flood of technically refined self-produced studio music, long before the digital revolution. Gould developed a radio style unique to his productions for the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation, called “contrapuntal radio”, in which several people overlap like a vocal fugue.

His Solitude Trilogy is the most famous of his countless TV and Radio production.

Interestingly, the film reveals the source of Gould’s idiosyncratic playing style. A childhood back injury leads to the special low piano chair his father built for him, which he used for the rest of his life. This leads to his characteristic clockwise swaying. His Toronto Conservatory piano teacher Alberto Guerrero taught the staccato attack, pulling down from very close to the keys rather than striking. Sitting low to the piano allowed Gould to master the Guerrero technique.