Margarethe von Trotta’s “Vision: From the Life of Hildegard Von Bingen,’’ portrays the practical minded 12th-century Benedictine nun, mystic, botanist, healer, playwright and composer, whose “visions” won her freedom from the structured confined world of her medieval convent.

Margarethe von Trotta’s “Vision: From the Life of Hildegard Von Bingen,’’ portrays the practical minded 12th-century Benedictine nun, mystic, botanist, healer, playwright and composer, whose “visions” won her freedom from the structured confined world of her medieval convent.

Margarethe von Trotta was one of the founding filmmakers (actress and director) of the New German Cinema of the 1970s (along with Herzog, Fassbinder, Rosa von Praunheim and her former husband Volker Schlöndorff. Von Trotta won the Golden Lion at the Venice Film Festival for “Marianne and Juliane” (1981.)

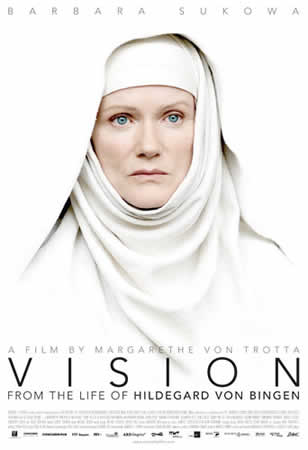

Barbara Sukowa, one of von Trotta’s frequent collaborators, plays the tough-minded nun who fought corruption in the church, running afoul of her Abbot Kuno (Alexander Held) who calls her a tool of the devil. Throughout her travails Brother Volmar (Heino Ferch) remains her loyal supporter and intercessory.

A fascinating prologue illustrates millennialist beliefs of the medieval world. Prostrated on the floor of the abbey, ardent believers await the end of the world, surprised when the sun rises once again.

Eight-year-old Hildegard, becomes a bride of Christ, to be raised “in humility” by Jutta von Sponheim, the daughter of one of the monastery’s greatest benefactors. Years pass. Magistra Jutta  dies. “I am a weak woman,” she tells the priest, who attempts to appoint her the new magistra. “My sisters will decide…I can only accept the post if my sisters vote for me” says the heroine Von Trotta positions as a prototypical feminist.

dies. “I am a weak woman,” she tells the priest, who attempts to appoint her the new magistra. “My sisters will decide…I can only accept the post if my sisters vote for me” says the heroine Von Trotta positions as a prototypical feminist.

Hildegard rebelled at the church’s patriarchal class structure, risking excommunication, she outed her visions, acquiring powerful supporters like The Margravine of Stade, Archbishop of Mianz and Kaiser Friedrich Barbarossa, much to the ire of Abbot Kuno. Elected Abbess by her sisters, she abolishes the cruel asceticism and mortifications, reforming her Convent into a humanist environment. She puts on self composed Morality plays, allowing the nuns to dance and dress in beautiful costumes during the performances.” God loves beauty, and we’re like virgins in paradise.” Lovely Richardis whirls like a dervish, delighting her doting Hildegard.

Von Trotta focuses on Hildegard’s savvy political sense. She courts important people and experiences miraculous recoveries from “near-death” to position herself above churchly sanctions and, when a young nun becomes pregnant, she establishes her own convent, removed from the immediate control of the local abbot. Shrewd Hildegard conflated her personal wishes and her God-sent visions to create the Rupertsberg monastery near Mainz, an important crossroads for European pilgrims and the seat of the archbishopric.

The close emotional ties between Hildegard, her oldest friend and surrogate mother Jutta (Lena Stolze), and the novice, Richardis von Stade (Hannah Herzsprung), who becomes Hildegard’s protégée, lends a hothouse melodramatic touch, hinting at a suppressed romantic love. In the end, Hildegard’s betrayed by her beloved protégé and intended successor. Crazed, foiled Hidegard wrote to Richardis’s family, the archbishop, even the Pope, trying to get Richardis’s reposting rescinded.

Art direction by Volker Schäfer and Margarethe von Trotta, production design by Heike Bauersfeld, and Axel Block’s exquisite cinematography use the original German medieval cloisters. The meticulous compositions resemble Gothic and Renaissance altar paintings, rather than the more typical realistic historical films. Von Trotta contrasts the candle lit dimness of the cloister (where women were enclosed for most of their natural life) with the sunlight gardens.

Sukowa inhabits the complex character, a mixture of political will, remarkable intellect, and passionate devotion. Sukowa, who has recorded rock and pop music, sings in the movie.

The film revels in moments of freedom: when Hildegard is lent a library by a traveling priest, her eyes are alit. After her first filmed “Vision” (a blazing light), she confesses to Brother Volmar, “I refused to do something I was appointed to do”, insisting God told her to “Write down what you see and hear.” Weren’t you afraid the visions weren’t sent from God but by the Devil?” Devout Hildegard replies “In such splendor only the Almighty  can appear. I am to warn mankind. To help him find his way back to God.” “Then you must warn mankind,” says Brother Volmar, who informs the Abbot.

can appear. I am to warn mankind. To help him find his way back to God.” “Then you must warn mankind,” says Brother Volmar, who informs the Abbot.

When she leads the nuns to their new convent, they join the travelers on the road. It’s a beautiful scene. Camping out on the site, she directs the builders to give her running water in all the working rooms, citing the Roman tradition to the dubious contractor. Surveying her new site at the well-traveled crossroads on the Rhine, she looks forward to meeting “heathen” Arabs and learning their medicine. There’s a wry, memorable shot of the nuns at their devotions, sitting on a log in the forest, surrounded by geese.

Some of the privileged nuns rebel at the work off building a new Convent and leave. Demanding the lands she was deeded by her sisters, Abbot Kuno mocks her, “You mean the sisters who left you because they couldn’t stand it?” Her ever-loyal provost Brother Volmar reports to the Abbot of Mianz, who awards her a water mill and the surrounding lands, making her new cloister secure.

There’s a delightful scene where Hildegard visits the Kaiser Friedrich Barbarossa, the King of Aachen (Devid Striesow) at the Barbarossa Palace. He scoffs at her demurral “I’m just a weak woman.” Grilling her about her Vision, she assures him he will be crowned Emperor. She counsels mercy, and warns against the greed of those who hold high office. The grateful Kaiser offers to introduce her to the learned men of science at his court, then teaches her to play chess (activities precluded for woman of the era.)

Hildegard, born into a noble family, started having visions as a child. Taught to read and write by the older nun Jutta, another noblewoman, with whom she was enclosed at the age of eight, she studied music and worked in the infirmary. She wrote plays, three books of visions and texts on the physical sciences. She communicated with the mystic Elisabeth of Schonau, Emperor Frederick I Barbarossa, popes Eugene III and Anastasius IV, Saint Bernard of Clairvaux who promoted her work at the Synod of Trier (1147-48) and diplomats (Abbot Suger), leaving a record of her correspondence. Despite the church’s limitation on public speaking, Hildegard made four popular speaking tours asking for churchreforms, at a time when woman were unacceptable as preachers. In an era when most did in their late thirties, Hildegard died at 81. Considered a Saint by Pope John Paul II and Pope Benedict XVI, she has still not been canonized. Her music was rediscovered in the 1990’s.