MEDIAS, Romania — With Europe slouching toward its own version of The Great Recession and economists divining the death of the euro, you wouldn’t think heading to Romania to check out another first-time film festival would be in sync with the global gestalt. Who has the resources to cover such small fry anymore? And why should anyone care about yet another one of these local festivals, which are spawned mainly to be municipal coffer-fillers anyway? Although they’ll probably stick around longer than the euro, these get-togethers rarely offer movies with any “legs” that can “travel” to non-regional cinemas.

But you’d be wrong to suppose any of this in the case of a town called Medias. This picturesque dot on the map is nicely named for being plopped in the middle of exotic Transylvania, a place imbued with its own quirky cinematic gestalt (cue the wolf howls and misty moons over those dreary Dracula castles).

But you’d be wrong to suppose any of this in the case of a town called Medias. This picturesque dot on the map is nicely named for being plopped in the middle of exotic Transylvania, a place imbued with its own quirky cinematic gestalt (cue the wolf howls and misty moons over those dreary Dracula castles).

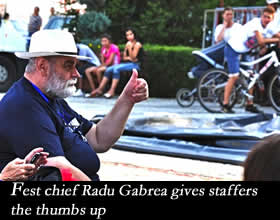

Around here you’ll find about as much of a native cinema culture as you would in, say, Chickasawhatchee. Which is why, with his new Medias Central European Film Festival (MECEFF), grizzle-bearded Radu Gabrea has proven  himself to be something of a Romanian Pied Piper. For six days in early September, the veteran Bucharest-based director, writer and producer (who resembles a cross between Leo Tolstoy and Orson Welles) gleefully lured a small caravan of award-winning films and filmmakers, critics and cineastes down the town’s cobbled streets and into Medias’ central square, happy to offer his own answer to Europe’s growing malaise.

himself to be something of a Romanian Pied Piper. For six days in early September, the veteran Bucharest-based director, writer and producer (who resembles a cross between Leo Tolstoy and Orson Welles) gleefully lured a small caravan of award-winning films and filmmakers, critics and cineastes down the town’s cobbled streets and into Medias’ central square, happy to offer his own answer to Europe’s growing malaise.

The premise was simple: celebrate award-winning movies from the seven countries of central Europe in a bid to spotlight the region’s cultural identity and its filmmakers. Each country – Czech Republic, Hungary, Austria, Poland, Romania and Slovakia (negotiations for a Slovenian film broke down, resulting in a no-show) – submitted its national prizewinner, although the politics of each country selecting such films, or even what “national prize” refers to, varied widely. There was an extra slot for a feature from a guest country outside the region, which this year was Israel. (Hence the numerical tag “7 + 1” appended to the festival’s name.)

The premise was simple: celebrate award-winning movies from the seven countries of central Europe in a bid to spotlight the region’s cultural identity and its filmmakers. Each country – Czech Republic, Hungary, Austria, Poland, Romania and Slovakia (negotiations for a Slovenian film broke down, resulting in a no-show) – submitted its national prizewinner, although the politics of each country selecting such films, or even what “national prize” refers to, varied widely. There was an extra slot for a feature from a guest country outside the region, which this year was Israel. (Hence the numerical tag “7 + 1” appended to the festival’s name.)

It’s a clever premise, too, because by inviting such award winners, Gabrea has dodged the most common pitfall of first-time film outings: mediocre movies with little reason for award acknowledgement.

Gabrea says he’s “sentimentally connected” to Medias because he shot one of his past 20 films and documentaries here, the feature Cocoşul decapitat (The Beheaded Rooster), not to mention that he once worked as a construction engineer 50 miles away. Clearly, with this new film venture, he’s committed thinking globally, acting locally.

He’s also eager to grow a broader, more adventurous local filmgoing audience. With 32,000 townspeople attending this year’s inaugural program – about 1 of every 4 adults in Medias – he’s made a good start. Screenings were often preceded by live stage

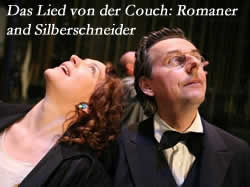

He’s also eager to grow a broader, more adventurous local filmgoing audience. With 32,000 townspeople attending this year’s inaugural program – about 1 of every 4 adults in Medias – he’s made a good start. Screenings were often preceded by live stage  shows and great dollops of Klezmer music from local bands. At MECEFF’s opening night screening of the quirky but superbly acted Mahler on the Couch (which won the festival’s Audience Prize), you could almost hear the collective sigh of relief from the visiting guests. All were grateful to be in the hands of a tightly-run and well-curated event. By the time the festival awarded it’s top prize on closing night to the smartly-shot Polish film Różyczka (Little Rose), it all seemed as much a celebration of regional bonhomie and reawakened cultural ambitions as it did of any one film.

shows and great dollops of Klezmer music from local bands. At MECEFF’s opening night screening of the quirky but superbly acted Mahler on the Couch (which won the festival’s Audience Prize), you could almost hear the collective sigh of relief from the visiting guests. All were grateful to be in the hands of a tightly-run and well-curated event. By the time the festival awarded it’s top prize on closing night to the smartly-shot Polish film Różyczka (Little Rose), it all seemed as much a celebration of regional bonhomie and reawakened cultural ambitions as it did of any one film.

Frankly, I found this local efficiency a bit  disorienting. After a 16-hour flight from Los Angeles, I arrived at Medias’ cinema beehive certain I’d get stung at least once by a bit of botched scheduling, an understaffed guest bureau or (tragically) perhaps a few bad buffets – the usual scourges of tyro festivals. But Gabrea’s buoyant executive director, Gabriela Bodea, and her 50 young English-speaking volunteers proved me wrong; MECEFF was pretty much

disorienting. After a 16-hour flight from Los Angeles, I arrived at Medias’ cinema beehive certain I’d get stung at least once by a bit of botched scheduling, an understaffed guest bureau or (tragically) perhaps a few bad buffets – the usual scourges of tyro festivals. But Gabrea’s buoyant executive director, Gabriela Bodea, and her 50 young English-speaking volunteers proved me wrong; MECEFF was pretty much  a model of efficiency and savvy programming. (A few English translators for the closing night awards show, however, would have been appreciated.)

a model of efficiency and savvy programming. (A few English translators for the closing night awards show, however, would have been appreciated.)

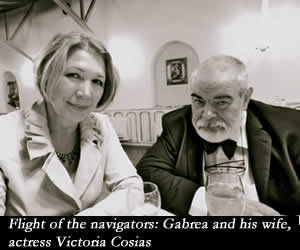

“We expected nothing when we first dreamed this up,” said Gabrea at the festival’s closing night dinner. He was enjoying a well-earned tsuika, a grappa-like local elixir made of plums. Next to him was his wife, the stunning Romanian film and theatre actress Victoria Cocias, who had just finished her duties as mistress of ceremonies. “But in particular the town’s mayor, Teodor Neamtu, has been very helpful to us. He’s a former pilot, you know, and he told me a little proverb about organizing such events,” Gabrea said with a grin. “Taking off is optional, but landing is compulsory!”

“We expected nothing when we first dreamed this up,” said Gabrea at the festival’s closing night dinner. He was enjoying a well-earned tsuika, a grappa-like local elixir made of plums. Next to him was his wife, the stunning Romanian film and theatre actress Victoria Cocias, who had just finished her duties as mistress of ceremonies. “But in particular the town’s mayor, Teodor Neamtu, has been very helpful to us. He’s a former pilot, you know, and he told me a little proverb about organizing such events,” Gabrea said with a grin. “Taking off is optional, but landing is compulsory!”

“Yes,” added Cocias. “I wasn’t sure about anything when we took off, but I can see that MECEFF has now landed successfully.”

“Even though at first you told me you didn’t trust me to fly?” Gabrea teased.

“Even though at first you told me you didn’t trust me to fly?” Gabrea teased.

“No, it was just that none of us knew where we’d end up!” she replied. “But we were all onboard, no matter what happened.”

“You see?” Gabrea turned to me. “Even when she is mean to me, she is my heavenly protector!”

More seriously, Gabrea’s inaugural landing is a reminder that the countries of central Europe have shared an extraordinary cultural unity over the centuries, and Gabrea wants his native Transylvania – with its stewpot heritage of Romanians, Hungarians and Germans – to be  acknowledged in this context. Much of that traditional unity was shattered during the Cold War era by the Eastern Bloc’s oppressive model of Soviet bureaucratic culture. A renewed regional identity for “central” Europe didn’t begin to emerge until the 1990s.

acknowledged in this context. Much of that traditional unity was shattered during the Cold War era by the Eastern Bloc’s oppressive model of Soviet bureaucratic culture. A renewed regional identity for “central” Europe didn’t begin to emerge until the 1990s.

Today, the challenges for the region are of the reverse dynamic: trying, for example, to integrate perhaps too quickly into a European Union dominated by the different bureaucratic systems of France (centralized) and Germany (federalized). “The history of this region has so many tensions and contradictions,” German critic and writer Wolfgang Ruf told me at the festival, where he was serving on MECEFF’s competition film jury (he was a former director of the Oberhausen Film Festival). “A festival like this one can help establish a real and authentic regional identity for Central Europe, much like the Karlovy Vary festival in the Czech Republic has started to do. Even in Germany, the picture of Romania is full of clichés, ja?”

to integrate perhaps too quickly into a European Union dominated by the different bureaucratic systems of France (centralized) and Germany (federalized). “The history of this region has so many tensions and contradictions,” German critic and writer Wolfgang Ruf told me at the festival, where he was serving on MECEFF’s competition film jury (he was a former director of the Oberhausen Film Festival). “A festival like this one can help establish a real and authentic regional identity for Central Europe, much like the Karlovy Vary festival in the Czech Republic has started to do. Even in Germany, the picture of Romania is full of clichés, ja?”

Vampires and demons and wolves, indeed. Still, Transylvania’s tourism industry relishes this hoary old gothic schtick. And why not? It’s good for business. Here, for example, you can find plenty of fortresses flogging themselves as “Dracula’s Castle” (Bran Castle, Poenari Castle and Hunyad Castle, to name a few.) Never mind that author Bram Stoker never set foot in Romania and knew nothing of these daunting piles, only latching onto the name Dracula by reading a book about Prince Vlad III (a.k.a. Vlad the Impaler), whose family name was Dracul. Still, the castles are packed with gawkers. In tourist towns like Bran and Sighisoara you can’t help cringing at all the cheap stands hawking Dracula mugs and fridge magnets, while some poor sod in a black robe and fanged mask hobbles over the cobblestones on stilts, posing with little Petru and Larisa for their snap-happy parents. Is Transylvanian Disneyworld far behind?

Vampires and demons and wolves, indeed. Still, Transylvania’s tourism industry relishes this hoary old gothic schtick. And why not? It’s good for business. Here, for example, you can find plenty of fortresses flogging themselves as “Dracula’s Castle” (Bran Castle, Poenari Castle and Hunyad Castle, to name a few.) Never mind that author Bram Stoker never set foot in Romania and knew nothing of these daunting piles, only latching onto the name Dracula by reading a book about Prince Vlad III (a.k.a. Vlad the Impaler), whose family name was Dracul. Still, the castles are packed with gawkers. In tourist towns like Bran and Sighisoara you can’t help cringing at all the cheap stands hawking Dracula mugs and fridge magnets, while some poor sod in a black robe and fanged mask hobbles over the cobblestones on stilts, posing with little Petru and Larisa for their snap-happy parents. Is Transylvanian Disneyworld far behind?

Light-fingered gypsies are another bit of local lore, and while plenty of Romani can be found manning the roadside flea markets and building their massive domiciles along the highways (funding from where, exactly?), you’ll find many more streetwise gypsies in cities like Cologne than you will in Bucharest. And  in France, Ruf reported, they’ve discovered a nifty ruse. “Sarkozy’s government started rounding them up and giving them each 100 euros before deporting them back to Romania,” he laughed. “But the gypsies developed it as a business model! They kept coming back again and again.” Touché for entrepreneurism.

in France, Ruf reported, they’ve discovered a nifty ruse. “Sarkozy’s government started rounding them up and giving them each 100 euros before deporting them back to Romania,” he laughed. “But the gypsies developed it as a business model! They kept coming back again and again.” Touché for entrepreneurism.

In Medias, however, you’ll find few of these regional oddities. With the inauguration of MECEFF, hard-to-see foreign movies are themselves becoming part of the local lore, giving the townsfolk a fresh feeling of cultural community. I ran into a high school teacher at one of the rare Yiddish film screenings in the local synagogue (which hasn’t seen a religious service in 15 years), who was happy to tell me he’d never seen movies like these before, even in Bucharest. The next day at an outdoor screening I saw him again, with a couple of his students in tow. Says Gabrea: “This year you had a very special feeling among the people. We are starting to evolve a new film culture.” While the mainstream

In Medias, however, you’ll find few of these regional oddities. With the inauguration of MECEFF, hard-to-see foreign movies are themselves becoming part of the local lore, giving the townsfolk a fresh feeling of cultural community. I ran into a high school teacher at one of the rare Yiddish film screenings in the local synagogue (which hasn’t seen a religious service in 15 years), who was happy to tell me he’d never seen movies like these before, even in Bucharest. The next day at an outdoor screening I saw him again, with a couple of his students in tow. Says Gabrea: “This year you had a very special feeling among the people. We are starting to evolve a new film culture.” While the mainstream foreign film journalists don’t yet know or care much about MECEFF, the locals certainly do, and such is how new cultural identities for a region are born.

foreign film journalists don’t yet know or care much about MECEFF, the locals certainly do, and such is how new cultural identities for a region are born.

My flight to Medias from L.A. landed at Cluj, a major cultural hub and home of the better-known Transylvanian International Film Festival, which I had attended only three months earlier (this was clearly my Transylvanian Summer). My assigned “chauffeur” for the festival, a cheery retired oboist named Valentin, had brought with him his English-speaking niece and festival translator, Thea Luca, so the comfy umbrella of one big happy “family” opened upon arrival. (It opened wider when I discovered Valentin was the husband of executive director Gabriela, a nifty bit of family recruitment).

My flight to Medias from L.A. landed at Cluj, a major cultural hub and home of the better-known Transylvanian International Film Festival, which I had attended only three months earlier (this was clearly my Transylvanian Summer). My assigned “chauffeur” for the festival, a cheery retired oboist named Valentin, had brought with him his English-speaking niece and festival translator, Thea Luca, so the comfy umbrella of one big happy “family” opened upon arrival. (It opened wider when I discovered Valentin was the husband of executive director Gabriela, a nifty bit of family recruitment).

After a night’s rest in a local hotel, Valentin spirited me off the next morning on a two-hour drive through miles of sheep-strewn hills and pastel Saxon villages, happy we could communicate in half-fractured French as we zipped past horse-drawn carts and gypsy road stands. Soon we arrived at Medias’ medieval town square, where the view from my gabled hotel room spanned a picture-postcard park framed by a 15th-century church. Later I discovered the church was run by a young German priest, who occasionally hosted evening film screenings in the church gardens. It’s also where a most extraordinary 1/8-size replica of the same church resides, made entirely of vines by a gypsy artist. Nearby were plenty of ratskeller bars to lubricate those late-night film chats and wash down the ubiquitous (and free) meat-and-cheese buffets.

After a night’s rest in a local hotel, Valentin spirited me off the next morning on a two-hour drive through miles of sheep-strewn hills and pastel Saxon villages, happy we could communicate in half-fractured French as we zipped past horse-drawn carts and gypsy road stands. Soon we arrived at Medias’ medieval town square, where the view from my gabled hotel room spanned a picture-postcard park framed by a 15th-century church. Later I discovered the church was run by a young German priest, who occasionally hosted evening film screenings in the church gardens. It’s also where a most extraordinary 1/8-size replica of the same church resides, made entirely of vines by a gypsy artist. Nearby were plenty of ratskeller bars to lubricate those late-night film chats and wash down the ubiquitous (and free) meat-and-cheese buffets.

Every day after the morning screenings, tour buses chugged festival guests to nearby castle wineries, folk dancing events, pristine lakes and medieval fortresses snuggled between the fairytale towns of Sibiu and Sighisoara. If soaking up regional culture was the aim, Gabrea and friends had prepared the perfect Petri dish for film appreciation to flourish. (It didn’t hurt that the dish was filled with generous helpings of tsuika and fine local wines.)

Every day after the morning screenings, tour buses chugged festival guests to nearby castle wineries, folk dancing events, pristine lakes and medieval fortresses snuggled between the fairytale towns of Sibiu and Sighisoara. If soaking up regional culture was the aim, Gabrea and friends had prepared the perfect Petri dish for film appreciation to flourish. (It didn’t hurt that the dish was filled with generous helpings of tsuika and fine local wines.)

In the interims there was a respectable menu of 45 films and half a dozen seminars, including sections honoring legendary Czech filmmaker Istvan Svabo (I was sad to miss a chance to revisit his superbly wry Closely Watched Trains) and Romanian documentary filmmaker Copel Moscu.

In the interims there was a respectable menu of 45 films and half a dozen seminars, including sections honoring legendary Czech filmmaker Istvan Svabo (I was sad to miss a chance to revisit his superbly wry Closely Watched Trains) and Romanian documentary filmmaker Copel Moscu.  Another focused on eight restored Yiddish feature films produced between 1923 and 1938. There was a rare screening of the 1937 feature, The Dybbuk, based on the seminal play of Jewish and Yiddish theatre, in the packed anteroom of the synagogue, and in the presence of Romania’s Israeli ambassador.

Another focused on eight restored Yiddish feature films produced between 1923 and 1938. There was a rare screening of the 1937 feature, The Dybbuk, based on the seminal play of Jewish and Yiddish theatre, in the packed anteroom of the synagogue, and in the presence of Romania’s Israeli ambassador.

The Dybbuk is an important historical artifact and for that reason alone was worth a look. But sadly, I found it marred by too much declamatory acting (think Delsarte) and too many overextended scenes, both which pulled much of the punch from this tale of a bride

possessed by a dead man’s soul.

possessed by a dead man’s soul.

More rewarding was the seminar by jury member Costel Safirman and guest Sharon Rivo on Israel’s Jerusalem Film Center and Brandeis University’s National Center for Jewish Film, respectively. The latter is an extraordinary collection, headed by Rivo, of 30,000 prints and 8,000 masters of Jewish films and other materials – the largest such archive outside of Israel. Also notable was Amy Kronish’s seminar on contemporary issues in Israeli and Palestinian society.

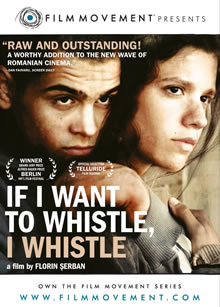

But it was the films that really set the scene and kept guests chattering in the ratskellers. Based on a stage play, Romanian director Florin Şerban’s If I Want to Whistle, I Whistle is a remarkably  affective first-feature about a young prisoner, soon to be released, who wreaks violence in his quest both to save a younger brother’s future and to realize a naïve dream of momentary romance. The movie, which was Romania’s entry for this year’s foreign film Oscar race, reaches far beyond the usual clichés of prison hostage drama. It also earned its young star, George Pistereanu, MECEFF’s best actor award and Şerban the festival’s directing trophy. It was certainly my favorite of the competition films I saw.

affective first-feature about a young prisoner, soon to be released, who wreaks violence in his quest both to save a younger brother’s future and to realize a naïve dream of momentary romance. The movie, which was Romania’s entry for this year’s foreign film Oscar race, reaches far beyond the usual clichés of prison hostage drama. It also earned its young star, George Pistereanu, MECEFF’s best actor award and Şerban the festival’s directing trophy. It was certainly my favorite of the competition films I saw.

In Little Rose, an affair between an abusive Polish secret agent and a young woman turns toxic when she finds herself falling for a much older Jewish professor whom he’s assigned her to spy on. Director Jan Kidawa-Błoński’s film takes place shortly after Israel’s Six Day War in 1967, when the Polish Secret Service began its campaign again Jewish intellectuals, and it becomes steadily more convincing as “Little Rose” (her code name) is relentlessly pulled deeper into the film’s spreading sand trap of political and emotional betrayal. It also makes effective use of original footage from the late 60’s anti-Communist protests in Warsaw. The only blatantly false note lies in the casting of the professor’s mother, who appears hardly a day older than her sexagenarian son.

professor whom he’s assigned her to spy on. Director Jan Kidawa-Błoński’s film takes place shortly after Israel’s Six Day War in 1967, when the Polish Secret Service began its campaign again Jewish intellectuals, and it becomes steadily more convincing as “Little Rose” (her code name) is relentlessly pulled deeper into the film’s spreading sand trap of political and emotional betrayal. It also makes effective use of original footage from the late 60’s anti-Communist protests in Warsaw. The only blatantly false note lies in the casting of the professor’s mother, who appears hardly a day older than her sexagenarian son.

One of the most popular and gleefully deceptive entries was the docudrama The Crazy World of Ute Bock, based on the true story of the 68-year-old activist who has become Vienna’s latter-day Mother Theresa for homeless refugees. I say deceptive because director Houchang Allahyari’s film, which won a handful of awards at Austria’s equivalent of the Oscars, dramatizes its sidewalk squabbles and office confrontations with a sleight-of-hand that almost convinces you they’ve spilled out a Fred Wiseman cinema vérité documentary (though Wiseman would hate that term). But of course it’s all staged, or most of it anyway. Felix Adlon told me that Bock is a bonafide rock star in Austria, receiving raucous standing ovations wherever she speaks, and it’s easy to see why. She’s sensationally charismatic, a pint-sized Grossmutti whose darling demeanor nonpluses her foes even as they hurl invective while she and her staffers fend off the pesky immigration police. Ute Bock is missing a U.S. distributor but little else to spread its wings. If it’s viewable anywhere Stateside in the future, you should certainly catch it.

One of the most popular and gleefully deceptive entries was the docudrama The Crazy World of Ute Bock, based on the true story of the 68-year-old activist who has become Vienna’s latter-day Mother Theresa for homeless refugees. I say deceptive because director Houchang Allahyari’s film, which won a handful of awards at Austria’s equivalent of the Oscars, dramatizes its sidewalk squabbles and office confrontations with a sleight-of-hand that almost convinces you they’ve spilled out a Fred Wiseman cinema vérité documentary (though Wiseman would hate that term). But of course it’s all staged, or most of it anyway. Felix Adlon told me that Bock is a bonafide rock star in Austria, receiving raucous standing ovations wherever she speaks, and it’s easy to see why. She’s sensationally charismatic, a pint-sized Grossmutti whose darling demeanor nonpluses her foes even as they hurl invective while she and her staffers fend off the pesky immigration police. Ute Bock is missing a U.S. distributor but little else to spread its wings. If it’s viewable anywhere Stateside in the future, you should certainly catch it.

The documentary Lia is a vibrantly shot and edited portrait of the Romanian-born Lia Van Leer, the founder of the Jerusalem Cinematheque and Israel Film archive along with the Jerusalem Film Festival. Affectionately known as the godmother of Israeli film, Lia, now 86, stubbornly refuses to retire; on the day I’m writing this, she opened her festival for its 28th edition. She’s someone I’ve spotted for years on the international festival circuit, scurrying through the halls of Cannes, Venice, Delhi or Berlin (where she won the Berlinale Camera this year for lifetime achievement) in her flowing white dress and matching hair, ready to plunge headlong into another screening of an obscure South Korean or Hindi opus. Back in the 1950s she and her husband, the industrialist Wim van Leer, trekked across Israel with a 16mm projector, screening films in kibbutzim and community settlements and founding the country’s first film club in 1955. If she’s seemed a lonesome figure since his death in 1991 (she since started a foundation in his name to help young filmmakers), she has kept the pain buried in her busy-ness, though she reveals moving glimpses of it through director Taly Goldberg’s skillful interviews. There are also judiciously chosen testimonials from Lia’s friends, woven with archival footage of her favorite movies, her lucky life and her very extended festival family. I didn’t know Lia well until I met her again in Lia, a work that digs as close to the soul of this remarkable lady as we’re likely to come.

The documentary Lia is a vibrantly shot and edited portrait of the Romanian-born Lia Van Leer, the founder of the Jerusalem Cinematheque and Israel Film archive along with the Jerusalem Film Festival. Affectionately known as the godmother of Israeli film, Lia, now 86, stubbornly refuses to retire; on the day I’m writing this, she opened her festival for its 28th edition. She’s someone I’ve spotted for years on the international festival circuit, scurrying through the halls of Cannes, Venice, Delhi or Berlin (where she won the Berlinale Camera this year for lifetime achievement) in her flowing white dress and matching hair, ready to plunge headlong into another screening of an obscure South Korean or Hindi opus. Back in the 1950s she and her husband, the industrialist Wim van Leer, trekked across Israel with a 16mm projector, screening films in kibbutzim and community settlements and founding the country’s first film club in 1955. If she’s seemed a lonesome figure since his death in 1991 (she since started a foundation in his name to help young filmmakers), she has kept the pain buried in her busy-ness, though she reveals moving glimpses of it through director Taly Goldberg’s skillful interviews. There are also judiciously chosen testimonials from Lia’s friends, woven with archival footage of her favorite movies, her lucky life and her very extended festival family. I didn’t know Lia well until I met her again in Lia, a work that digs as close to the soul of this remarkable lady as we’re likely to come.

I grew up listening to Mahler Symphonies and song cycles, but little did I know that old Gustav once paid a visit to Sigmund Freud’s office couch, tortured by his wife Alma’s passionate fling with pretty boy Walter Gropius (one of her many infamous literati liaisons). Apparently few others knew about it either, since the visit was only perfunctorily noted in a single line of Freud’s journal. Armed with this tantalizing tidbit, the ever-quirky Percy Adlon  and his son, Felix, decided to unravel one of the world’s oddest celebrity shrink sessions into the sturm und drang fantasia that is the delirious and delicious Mahler on the Couch.

and his son, Felix, decided to unravel one of the world’s oddest celebrity shrink sessions into the sturm und drang fantasia that is the delirious and delicious Mahler on the Couch.  Luck seems to have squeezed onto the couch, too, since Adlon père was able to cast most of his lead actors for the film from a single play he saw in Munich. The film offers impeccable performances from Johannes Silberschneider (Mahler) and, most memorably, the superb newcomer Barbara Romaner (Alma). Oozing the assurance of a screen veteran, the young Romaner inhabits her character with all the passion and command of a divine dybbuk. Despite some rather skittish (I almost wrote schizoidal) editing early on, the low-budget feature is easily one of the Adlons’ most accessible and enjoyable to date, and was an inspired choice for the festival’s opening night.

Luck seems to have squeezed onto the couch, too, since Adlon père was able to cast most of his lead actors for the film from a single play he saw in Munich. The film offers impeccable performances from Johannes Silberschneider (Mahler) and, most memorably, the superb newcomer Barbara Romaner (Alma). Oozing the assurance of a screen veteran, the young Romaner inhabits her character with all the passion and command of a divine dybbuk. Despite some rather skittish (I almost wrote schizoidal) editing early on, the low-budget feature is easily one of the Adlons’ most accessible and enjoyable to date, and was an inspired choice for the festival’s opening night.

Meanwhile, after two days of non-stop moviegoing it was time to hit the road again, courtesy of Valentin. Felix Adlon and I enjoyed an  afternoon traipsing through one of Transylvania’s medieval fortified castles in Biertan, a cinematic burg if ever there was one. Felix has a penchant for constructing scenarios in his head whenever he travels, and as soon as we set foot on the castle grounds, the head went into overdrive. “I believe I’ve found the location for my next film,” he mused, eyeing the towering turrets where a few Draculaesque bats were cruising the rafters. “Let’s get some photos.”

afternoon traipsing through one of Transylvania’s medieval fortified castles in Biertan, a cinematic burg if ever there was one. Felix has a penchant for constructing scenarios in his head whenever he travels, and as soon as we set foot on the castle grounds, the head went into overdrive. “I believe I’ve found the location for my next film,” he mused, eyeing the towering turrets where a few Draculaesque bats were cruising the rafters. “Let’s get some photos.”

In between shutter clicks he proceeded to unravel a scenario in the vein of The DaVinci Code, something about a man locked away in a castle ane who discovers mysterious coded table  carvings… But I’ll let the rest of it rest there, for fear of having Opus Dei on my back, not to mention Felix.

carvings… But I’ll let the rest of it rest there, for fear of having Opus Dei on my back, not to mention Felix.

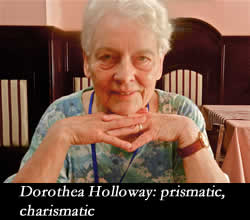

Such new friends popped up at MECEFF in generous clumps, along with old and dear ones, too. With her late husband, the much-beloved Ron (who served as my German bureau chief years back when I was international editor at The Hollywood Reporter), the actress and magazine editor Dorothea Holloway has been for decades a staple of the festival scene. Dorothea studiously avoided the group tours to burrow herself in the screenings, as befitted her competition jury duties. I enjoyed our breakfasts together and admired her commitment to continue publishing their renowned Kino magazine on German film, now in its 101st edition after 30-some years. Ron and Dorothea’s documentary chronicling the fall of the Berlin Wall in 1989, Mauertänzerinnen (Wall Dancers), is a sharply observed beam of history refracted through the prism of personal memory. It still lacks a distributor and deserves one.

as befitted her competition jury duties. I enjoyed our breakfasts together and admired her commitment to continue publishing their renowned Kino magazine on German film, now in its 101st edition after 30-some years. Ron and Dorothea’s documentary chronicling the fall of the Berlin Wall in 1989, Mauertänzerinnen (Wall Dancers), is a sharply observed beam of history refracted through the prism of personal memory. It still lacks a distributor and deserves one.

Other visitors included festival jurist and former attorney David Blum, a Brooklyn native who splits his time between Washington, D.C. and Sighisoara, where he helped restore a local cathedral before tackling another architectural challenge, his intriguing debut novel The Last Pottsville Warrior (six years in the making). A copy of it happily landed in my luggage before I left… The brilliant Bucharest journalist and founder of the financial newspaper Bursa, Florian Goldstein wields a wry wit and can actually tell some funny jokes about the global economic mess… Daniel Russu of Israel Educational Television came on several of Valentin’s “chauffeured” trips to the countryside, bringing a camera that proved essential when mine proved broken and disposable…and my old friend Laszlo Kantor.

Laszlo’s producing career had been watered nicely over the years by Hungary’s generous government film subsidies. But now his country’s tap is running dry, and Laszlo was nursing, between cigarettes, some economic frustrations of his own. Europe’s current money malaise was “making it miserably hard for filmmakers and their futures,” he reported – no surprise there. The good news is that the crisis has spurred Laszlo to take camera in hand (he’s also a cinematographer) and shoot his own stories, funding be damned. His new project chronicles a village priest who founded a school for Romanian orphans. “It’s my way of giving back and doing something…bigger,” he smiled.

Laszlo’s producing career had been watered nicely over the years by Hungary’s generous government film subsidies. But now his country’s tap is running dry, and Laszlo was nursing, between cigarettes, some economic frustrations of his own. Europe’s current money malaise was “making it miserably hard for filmmakers and their futures,” he reported – no surprise there. The good news is that the crisis has spurred Laszlo to take camera in hand (he’s also a cinematographer) and shoot his own stories, funding be damned. His new project chronicles a village priest who founded a school for Romanian orphans. “It’s my way of giving back and doing something…bigger,” he smiled.

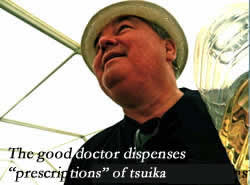

Finally, who could forget the festival’s unofficial party organizer and tsuika provisioner, the honorable and ebullient Petru Oprean, M.D.? The cherry-faced doctor hosted a group outing to the summer villa of HRH Prince Charles (a devotee of Transylvania, though he wasn’t in town) and could always be counted on to provide good spirits, in both senses of the term. Before I left Medias he stuffed my suitcase with two liters of his best local libation, which he prescribed as a curative “for all possible ailments.” Miraculously, the bag cleared customs.

Finally, who could forget the festival’s unofficial party organizer and tsuika provisioner, the honorable and ebullient Petru Oprean, M.D.? The cherry-faced doctor hosted a group outing to the summer villa of HRH Prince Charles (a devotee of Transylvania, though he wasn’t in town) and could always be counted on to provide good spirits, in both senses of the term. Before I left Medias he stuffed my suitcase with two liters of his best local libation, which he prescribed as a curative “for all possible ailments.” Miraculously, the bag cleared customs.

Toward the end of the festival, Valentin helped orchestrate a night of shameless fun at MECEFF, when a six-man ensemble revved up a dinner banquet with so much Roma, folk and Klezmer music that even the busboys boogied. Amid all the dancing and gorging and toasts, it was the night I discovered the glorious taragoto. This Hungarian instrument of Persian origin sounds like a voluptuous, throaty cross

night of shameless fun at MECEFF, when a six-man ensemble revved up a dinner banquet with so much Roma, folk and Klezmer music that even the busboys boogied. Amid all the dancing and gorging and toasts, it was the night I discovered the glorious taragoto. This Hungarian instrument of Persian origin sounds like a voluptuous, throaty cross  between a clarinet and saxophone – the Marlene Dietrich of reed instruments. For me, it was love at first toot. Wikipedia calls the ancient taragoto “a very loud and raucous instrument” best used for signaling warriors to battle. But that’s nothing like the modern variety, which could easily seduce the most bellicose boys to make love and not war. (The instrument can

between a clarinet and saxophone – the Marlene Dietrich of reed instruments. For me, it was love at first toot. Wikipedia calls the ancient taragoto “a very loud and raucous instrument” best used for signaling warriors to battle. But that’s nothing like the modern variety, which could easily seduce the most bellicose boys to make love and not war. (The instrument can sometimes be found in the orchestra pit f or the Shepherd’s Call in Act III of Wagner’s great fatal lust-fest, Tristan und Isolde). It certainly seduced me into making a hefty credit card purchase, when I later relieved a couple of local music stores of their entire taragoto CD collection, ready for burning onto my iPod back in L.A. True to Gabrea’s mission, Transylvania’s cultural umbrella had just opened a bit wider.

sometimes be found in the orchestra pit f or the Shepherd’s Call in Act III of Wagner’s great fatal lust-fest, Tristan und Isolde). It certainly seduced me into making a hefty credit card purchase, when I later relieved a couple of local music stores of their entire taragoto CD collection, ready for burning onto my iPod back in L.A. True to Gabrea’s mission, Transylvania’s cultural umbrella had just opened a bit wider.

As I left Medias, I wondered if there would be another MECEFF festival in 2012 to capitalize on the good spirits of this one. Despite the current bad fortunes of Europe, Gabrea assured everyone that, yes, “if we build it again, they will come.”

It might take a while for folks in Hollywood to schlep over to Transylvania, so to jump-start things why not spread a bit of their culture over here?

It might take a while for folks in Hollywood to schlep over to Transylvania, so to jump-start things why not spread a bit of their culture over here?

What about a festival section examining the famous Romanians in Hollywood history? There are plenty of them: Johnny Weissmuller and Bela Lugosi (both ethnic Hungarians born in today’s Romania), Lauren Bacall (French/Polish/Romanian), Winona Ryder (half Romanian) Dustin Hoffman (Russian Romanian Jew) and Harvey Keitel (Polish Romanian Jew), just for starters. Throw in Fran Drescher for good measure.

And that’s not to mention the Romanian writers, directors, producers and other below-the-liners who have famously toiled in Tinseltown.

Then it dawned on me that if I was already thinking about this “small fry” festival in bigger-fry terms, Gabrea’s ambitious experiment must have paid off. In a modest way, he had succeeded in putting the “central” back in Europe. His plucky new festival promised to have “legs.”

When I arrived home, I sent out a few emails thanking my hosts for all the hospitality and fine work. Then I turned on the iPod, poured myself a shot of tsuika from Petru’s stash, and began to replay the strange yet familiar movie in my head.

Festival and Romania photos by James Ulmer, Thea Luca and Mihai Andrei.