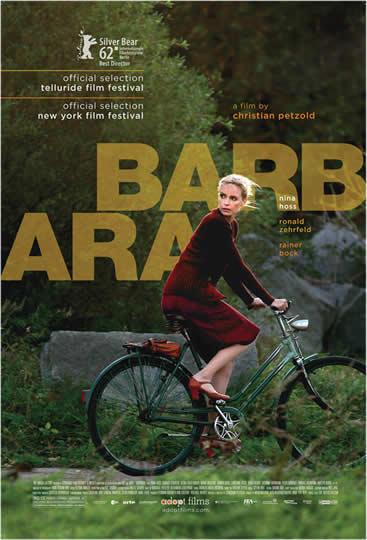

“Barbara”, Germany’s 2012 Oscar submission, summons a little seen world of East Germany circa 1980.

“Barbara”, Germany’s 2012 Oscar submission, summons a little seen world of East Germany circa 1980.

East German pediatric doctor Barbara Wolff (Nina Hoss) is banished from her prestigious Berlin hospital. Her request for an exit visa to the West has led to a disciplinary transfer to a rural clinic, where, presumably, she will be easier to control. Although the Stasi exert their control with random home and strip searches, Barbara continues to meet with her western lover Jörg (Mark Waschk) as he plans the last stages of her escape over the Baltic Sea to Finland. Rainer Bock (“The White Ribbon”) is strong as Klaus Schütz, the Stasi officer who harasses and humiliates Barbara.

She’s placed in a Spartan apartment, with a vigilant building manager. Barbara thinks, “No-one can be happy here.”

Barbara sulks, the shabby clinic is a comedown for the gifted workaholic, who acknowledges “the farmers and workers provided your education, and now it’s time to pay them back.” Wary (and rightfully so) of her superior, Barbara doesn’t mingle with colleagues, who describe her as “big city” arrogant. But her work ethic and smarts win them over.

It’s an environment in which both working too hard or not hard enough puts you under suspicion, in which colleagues are encouraged to spy and report on you. Her superior, gentle, hunky Dr. Andre Reiser (Ronald Zehrfeld) is fascinated by her, and yes, he is enlisted by the Stasi to report on her (he has his reasons,) But the conscientious doctor in him is drawn to her expert skills and closed off demeanor and an edgy courtship is in the offing.

An encounter with pregnant Stella (Jasna Fritzi Bauer), a hopeless young girl adept at escaping her juvenile work camp, begins Barbara’s slow emotional thaw. Andre and Barbara bond while tending Stella. She is loath to send the girl back to the “extermination camp” on the installment plan. This is a star-making breakout performance for Nina Hoss, who’s made five three earlier films with Petzold (“Jerichow”, “Yella” and “Wolfsburg” and the TV movie “Something to Remind Me”.) Hoss’s gifted performance is crafted from small responses in the eyes and lips, the set of her body, the grim aggressive way she chain smokes: all reveal a secretive woman with no-one to trust, trying to survive an exile until her escape West. Indeed, when we see her trysting with Jörg (she crawls into his hotel window) we see a different, relaxed woman, the one she will be one she’s free and in the West. Little by little, as she changes, Hoss draws us in. Her performance raises a film which, while adept at recreating a pervasive paranoid atmosphere, offers a somewhat simplified script with an aggravating coincidence in the last act. Petzold loses tension in other ways. The creeping pace, while fostering suspicion in the audience, allows plot choices to flatline. Instead of goosing out anxiety, the frequent wind tossed trees become expected.

On the plus side, Christian Petzold recreates the baleful effects of the Big Brother society of later day communism. Going further than” The Loves Of Others”, Petzold shows how the Stasi infiltrated every day lives, poisoning both professional and intimate relationships from the bottom up. The genius of his approach (a little under-served by the script) is showing how his characters, aware of the ongoing surveillance, manage to carve out very human, unexpected choices.

As Barbara and Andre’s mutual appreciation grows, Western lover Jörg suffers by comparison. While eager to give her everything, his smug sexist remarks irritate,” You will not have to work, I have enough income for both of us.”

There’s a sexist undertone: Western men cherrypicking compliant woman with offers of Western freedom. In a telling scene, at the hotel where she covertly trysts with Jörg, Barbara meets another woman (Susanne Bormann): studying a gift catalogue of Western kitsch, the naïf Steff, fresh from a loud off-screen bout of love-making, waits for her promised gift and more from Jörg’s colleague Gerhard (Peter Benedict). It’s one of many scenes documenting the dysfunctional Soviet society circa 1980.

There are ingratiating scenes of Ostalgia, like the group of waitresses lying on the floor with their legs on the wall to rest their tired feet. Andre’s hospitality, the meal he makes, the bike rides, show a softer side of life. At first we are charmed by the unfamiliar rural locations, the sunny coastal town with its ocean overlooks, until the creeping paranoia asserts itself. The seductive countryside is a clever choice, allowing the oppression to work on us subliminally. Petzold’s distancing devices avoid emotional involvemen. If anything, the film is so reserved, we feel like spies observing the distant dilemmas of the main characters.

Kade Gruber’s brilliant production design nails the stripped down sub standard world of the East German Soviet era. DP Hans Fromm’s world of static medium-long shots, seemingly set in a permanent twilight hour (and shot in natural light), establishes the claustrophobic Orwellian atmosphere. Almost no music softens the tale- leaving evocative touches like a radio broadcast of the Moscow Olympics, or the insistent wind, to season the mood.

In a quiet show of control, Petzold and Fromm’s camera creeps up on Barbara, echoing the change in her inner life, By the end, we are seeing Barbara’s P.O.V. Winner: Awards Silver Bear (Best Direction) Berlin 2012, German Film Award 2012 (Best Film: Silver).