Ben Shapiro’s “Gregory Crewdson: Brief Encounter” joins a short list of exceptional films about the art process. Thomas Riedelsheimer’s 2001″ Rivers and Tides” observes British artist Andy Goldsworthy, who creates intricate and ephemeral sculptures from natural materials such as rocks, leaves, flowers, and icicles, capturing them in natural movement in his camera. Jeff Malmberg’s stunning “Marwencol” studies folk artist/ photographer Mark Hogancamp whose self medication for the brain damage he suffered in a savage bar beating became the meticulously created 1/6-scale World War II-era Belgian imaginary of Marwencol, First time director Jeff Malmberg’s interest lead to a Gallery show in New York City.

Ben Shapiro’s “Gregory Crewdson: Brief Encounter” joins a short list of exceptional films about the art process. Thomas Riedelsheimer’s 2001″ Rivers and Tides” observes British artist Andy Goldsworthy, who creates intricate and ephemeral sculptures from natural materials such as rocks, leaves, flowers, and icicles, capturing them in natural movement in his camera. Jeff Malmberg’s stunning “Marwencol” studies folk artist/ photographer Mark Hogancamp whose self medication for the brain damage he suffered in a savage bar beating became the meticulously created 1/6-scale World War II-era Belgian imaginary of Marwencol, First time director Jeff Malmberg’s interest lead to a Gallery show in New York City.

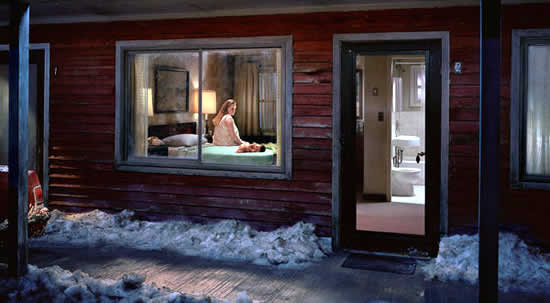

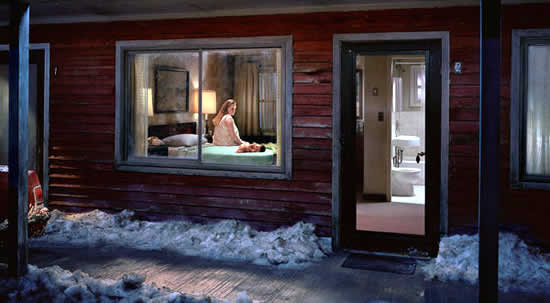

Ben Shapiro (“Paul Goodman Changed My Life”, “Election Day”) spent ten years following surrealist photographer Crewdson through most of the production of his epic series “Under The Roses.” Crewdson’s elaborately produced and staged large single frame photos, shot with a movie crew, then recreated in post production, seem to be single frames from an unknown movie, or better yet a dream. As narrative objects, they are as disturbing asthe flash cards of the ubiquitous Minnesota Multiphasic Personality Inventory (MMPI, or the the collaged graphic novels of Max Ernst.

Crewdson comes by his troubling subtext organically. His sychiatrist father’s office was in the basement of their Park Slope home. He remembers listening through the floorboards, trying to hear the secrets unraveling below.

Crewdson thought he might follow in his father’s footsteps but un-diagnosed dyslexia made him a dulsatory student (he did get into Yale!). He took a photography class to impress a girl, and that was it.

An uncharacteristic teenage visit to the Museum Of Modern Art, with is father, to view a Diane Arbus, changed his life. Crewdson identifies with Arbus, though the production of their work is very different. Arbus found her off kilter images in life; Crewdson meticulously works to illustrate moments in his mind.

Explaining his fascination with her work, he discusses her image of a Jewish giant at home with his parents in the Bronx. The “dislocation” of the giant, looming over the Gemütlichkeit middle-aged couple in their living room was a goad to Crewdson. (“Blue Velvet” is another inspiration, as was Cindy Sherman. Hitchcock’s “Psycho” is subtly referenced in one of his epic, deeply layered images.)

His photography classes at Yale were dominated by realist photography, but his work was already working the line between realism and narrative, recalls teacher Laurie Simmons.

Crewdson was part of the short lived punk band the Speedies, whose sole hit the ironically titled “Let Me Take Your Photo,” was rediscovered for the Hewlett Packard “Road Trip” commercial.

His latest work is a tone poem of melancholy. Gravid figures reminiscent of Balthus’ secretive figures are set in a Hopper or Wyeth landscape writ large.

Crewdson, who summered in the western Massachusetts town of Pittsfield, often returns to a lake where long distance swims help his creative process, haunts the same series of small towns in decline. (Norman Rockwell, portrayed the same local in his sunny portraits of American life.)

Shooting over and over again in the same locations wins him local support and cooperation. The photographer, who used to do large-scale guerilla stints, now can shut down entire streets for his shoots. “He shuts streets down and does wacky stuff,” a self-described picker (and one of the subjects of Crewdson’s photos) explains.

Ben Shapiro’s engrossing 77-minute documentary (he shot it himself) is a portrait of the meticulous obsessional work Crewdson deploys to create his haunting liminal images. Books barely do justice to the luminous often 30’X40′ gallery images.

Gregory shoots numerous still of the same camera setup on 8 x 10 color negative film, and then crafts a final image in postproduction lifted and replacing sections of the shot until he achieves the lapidarian glowing final image.

He works on location and on sound stages, overseeing a set designer, an art director, a lighting tech and director of photography. Shooting in dusk or “Golden Hour” DP Rick Sands (Crewdson’s alter-ego) typically using about 70 HMI studio light rigs. (Sands revealed in a recent interview that they have used as many as 134 rigs.)

Fogging the streets, Crewdson will wait indefinably to capture the images he’s hunting. Minute adjustments relayed through an assistant director subtly shift his subjects. “Look sad” is a frequent direction. In one amusing sequence the crew waiting all night for an infant to fall asleep. In another epic shot, the crew waited hours for snowfall to blanket a street, only to have an electric company truck drive through shot to fix a street light.

Bars, motels, empty streets are his realm, the place he baits his trap for what Crewdson calls “backdrops for a more submerged psychological drama.” “Every artist has one central story to tell. The struggle is to tell and retell that story over again – and to challenge that story. It’s the defining story of who you are.” A MUST SEE