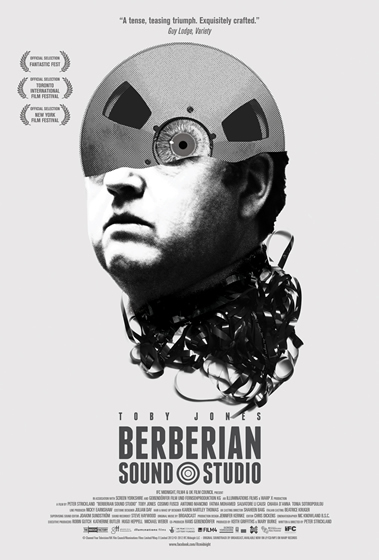

1976: Berberian Sound Studio is one of the cheapest, sleaziest post-production studios in Italy. Only the most sordid horror films have their sound processed and sharpened in this studio. Gilderoy, a naive and introverted sound engineer from England is hired to orchestrate the sound mix for the latest film by horror maestro, Santini. Thrown from the innocent world of local documentaries into a foreign environment fuelled by exploitation, Gilderoy soon finds himself caught up in a forbidding world of bitter actresses, capricious technicians and confounding bureaucracy.

1976: Berberian Sound Studio is one of the cheapest, sleaziest post-production studios in Italy. Only the most sordid horror films have their sound processed and sharpened in this studio. Gilderoy, a naive and introverted sound engineer from England is hired to orchestrate the sound mix for the latest film by horror maestro, Santini. Thrown from the innocent world of local documentaries into a foreign environment fuelled by exploitation, Gilderoy soon finds himself caught up in a forbidding world of bitter actresses, capricious technicians and confounding bureaucracy.

Obliged to work with the hot-headed producer Francesco, whose tempestuous relationships with certain members of his female cast threaten to boil over at any time, Gilderoy begins to record the sound for ‘The Equestrian Vortex’, a hammy tale of witchcraft and unholy murder typical of the ‘giallo’ genre of horror that’s all the rage in Italy.

Reading-born writer/director Peter Strickland’s first feature film Katalin Varga was made entirely independently over a four year period. It went on to win many awards including a Silver Bear in Berlin and The European Film Academy’s Discovery of the Year award in 2009. Prior to this, Strickland made a number of short films including Bubblegum and A Metaphysical Education. He also founded the musique-culinary group, The Sonic Catering Band in 1996, releasing several records and performing live throughout Europe. The band also released field recordings, sound poetry and modern classical in very limited vinyl editions.

Bijan Tehrani: How did you come up with the idea for Berberian Sound Studio?

Peter Strickland: It was a number of things. I wanted to show the mechanics of the film. Usually, cinema is only concerned with the illusion the whole thing and the mechanics are completely hidden but here it’s the opposite: you only see the mechanics and the illusion is hidden.

BT: How did you actually go about writing the screenplay? Did you also write it yourself?

PS: Yes, I started it quite a while ago, in May 2006. I think I wrote it as a five reel act, and then it became more flared as it progressed. I really wanted to make a visual film about sound, where you could actually touch the sounds, and show the vegetables that are behind those sounds. It’s almost textile and sensual in some way.

BT: How much did your work in music help you create Berberian Sound Studio?

PS: It helped massively really. We’ve been doing similar things, where we’ve taken very ordinary, domestic sounds, especially in the kitchen, and transformed the ordinary into the extraordinary just with simple processes – through amplification, editing. We used similar effects. What we tried to do with the band was try to be very realistic. In the film, every single sound that you hear can be physically placed. Nothing in the film is coming from a character’s head. It gave us freedom because normally in a film you have to fade the music out or round it up, and such, but in this film we could just stop the music. We did it in such a way that we were doing the sound and the edit at the same time. So if we stopped the music, we’d find a shot of Toby Jones switching the machine, punching the sound out.

BT: For those who have been involved in filmmaking, or even for an ordinary audience, it’s interesting to see how creative sound engineers were before everything became digital.

PS: Yes. If you read about Ben Burtt who did Lucas’s films and Spielberg, his story is remarkable. In Raiders of the Lost Ark, that scene where that big boulder is coming after Indiana Jones in the beginning, I think he put a car in reverse on a hill to record the sound. Or Alan Splet, all the sounds he created. The difference is these people were given a lot of time and money; now everything is digital. You can get the sounds of Ben Burtt or Alan Splet in five seconds if you get the right plug-in, but to me that’s not the point. The point is to explore, examine and perhaps come across happy accidents. That creativity has gone to some degree. I think now the focus is more on mixing sound more than recording. People don’t record sounds anymore because they just buy sound libraries. I remember having an argument about using cicadas for a sequence. My designer said he had about 2 gigabytes of cicadas and I said why don’t we go somewhere and record them? The attitude changes a little bit with digital.

BT: There are film critics who have said your work reminds them of the early work of Polanski. I would say the way you deal with the characters and the drama reminded me of Hitchcock. Have you been a fan of his?

BT: There are film critics who have said your work reminds them of the early work of Polanski. I would say the way you deal with the characters and the drama reminded me of Hitchcock. Have you been a fan of his?

PS: Not really. I’ve seen his work but I’ve never really warmed to him the way I did for other directors. I guess directors I fell in love with were some of the American underground people, like Jonas Mekas, Stan Brakhage, the early David Lynch, especially when I was growing up – Eraser Head, the Elephant Man, I actually really love Polanski as well, especially The Tenant. Luis Bunuel was a huge part of my life. But Hitchcock… maybe I just rebelled because I knew he was a classic.

BT: Picking Toby Jones for the main part was amazing. How did you decide on him and how did you work with him?

PS: We were going through various suitable faces and Toby’s name came up at one of the meetings. He’d done a radio play so he already some kinds of feelings about it. In terms of look, he had the right look for the character – the right face and posture. When we spoke, we spoke a lot about music and sound. The main talent for him was to keep the audience involved but stay very non-descriptive; there’s nothing big about his performance, it’s all contained and that’s the hardest thing for an actor. Usually, you engage by playing big. Everything’s so mute here. He kept a chart in his room of the ups and downs of Gilroy and had a very concrete idea of the character in his mind. A lot of actors, I find, don’t like abstractions, they talk in very concrete, realistic terms.

BT: What is the next project you are involved with?

PS: The work I’m going to start is the Duke of Burgundy. We are making it with Andy Stark and Ben Wheatley. I think we are shooting in August; I am getting a bit nervous. As with all those things, it might fall through. I hope not.