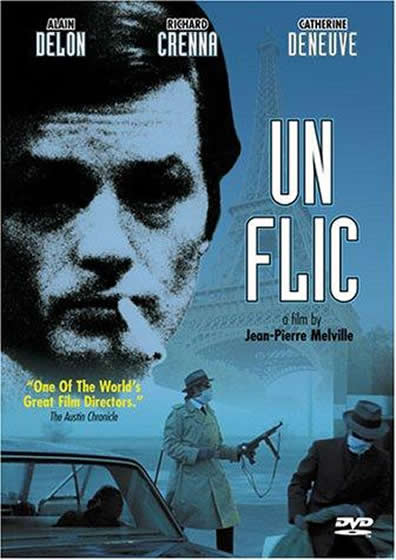

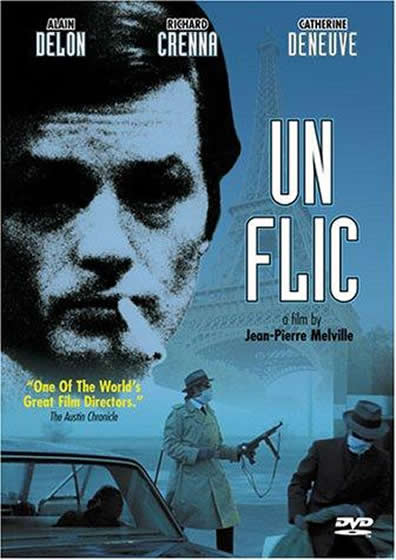

I’ve never seen a bad Melville picture. Even this last feature, saddled with several unfortunate exterior sets and a train heist shot in miniatures that hasn’t aged well, has one of the most beautiful set piece’s Melville ever conceived.

I’ve never seen a bad Melville picture. Even this last feature, saddled with several unfortunate exterior sets and a train heist shot in miniatures that hasn’t aged well, has one of the most beautiful set piece’s Melville ever conceived.

Melville transformed the American Crime Film into a uniquely stylish series of existential crime and police procedurals. Every iconic American cliché is retooled as a stylized signifier.

And plenty of Americans borrowed back. I’m guessing Michael Mann’s “Heat” is a version of “Un Flic” (Filmed in 1972, it was finally released in the U.S as “Dirty Money” in 1979.) Walter Hill, Scorcese and Tarentino all owe him a debt.

Melville opens with a quote by 18th-Century criminologist Francois-Eugene Vidocq: “The only feelings mankind has ever inspired in policemen are those of indifference and derision.” (Vidocq, a criminal turned policeman and considered the father of the French Police Force, private investigation and modern criminology) inspired many films, including Douglas Sirk’s witty “A Scandal in Paris” with George Sanders playing Vidocq.)

Alain Delon, who played a hitman in Melville’s “Le Samourai” and an elegant thief in “Le Cercle Rouge”, here essays bored cop Edouard Coleman. It’s just a job. Coleman tools around town in his American Car. Every shift is the same. The phone rings in his car, His assistant answers. “I’ll pass you to him.” Coleman listens impassively, says “Where’s that?” and “We’re going. I’ll call you back later.” and takes off. Nothing changes his demeanor or Melville’s ironic minimalism. Coleman’s rounds involve a drug-smuggling gang, bank robbers, as well as the sorts of intimate crimes that affect the well-to do.

Commissioner Coleman, whose buddy, nightclub owner Simon (briliantly played by Richard Crenna) turns out to be the criminal mastermind he’s seeking, struggles with a personal sense of honor, and the exigencies of his job, which are often at odds. As does his alter ego Simon. The heated language of looks that plays between them in every scene is a lexicon of the West’s mythology of macho, and the fatality it enshrines.

Coleman and Simon are one of several pairs of doubles.

Gaby (Valerie Wilson) the informer, a smitten Transvetite hooker, dresses and looks like Cathy. His/her visits to Coleman are perfumed with suppressed unrequited desire. Or is it, Melville lets it simmer in your unconscious.

Crenna builds an immensely likable criminal, and though betrays a colleague with dispatch, you’re loath to hate him. Simon’s gang of criminals is a dour, middle-aged, workaday bunch; all of them trying to pull off a final job so they can retire. Tough guy Lou Costa (Michael Conrad) seems like a career criminal. One, Paul Weber (Riccardo Cucciolla), an apparently meek, unemployed bank manager, disguises his heists from his worried wife (Simone Valère), as a series of job interviews. Simon’s as swank as Coleman and they share a woman in common. Simon’s moll Cathy (Catherine Deneuve) has been having an affair with Coleman, and Melville’s almost mute script introduces this in a scene that relies on the audience’s ability to read nuance. Deneuve’s youthful perfection is icy and astonishing. The two men enjoy each other, consciously or unconsciously linked by Cathy. Simon’s bar, where Coleman noodle on the piano is their DMZ.

Like Hefner’s imaginary Playboy, they both appreciate the finer thinks of life. Delon can ID a Maillol sculpture when a rich john is robbed by his young hustler. Simon plans his heist at the Louvre’s Impressionist gallery

Melville employs a Brechtian distancing effect that gives the film a hypnotic quality. Nowhere is that more evident than the exquisite bank heist perpetrated on an oddly empty Riviera seaside bank in St. Jean-De-Monts.

A late afternoon winter storm blows across a deserted seaside Esplanade. A modern building wraps across the widescreen image. The camera, poised at the building’s corner creates a composition as Modernist as Mondrian or Leger, and existential as Antonioni.

The Esplanade de la Mer in St Jean de Monts was full of seaside apartments just completed when Melville shot. Other locations include the train station in La Roche-sur-Yon. Melville and cinematographer Walter Wottitz take a highly realistic scene and give it the clinical surreality of Paul Delvaux or de Chirico. The sounds that underscore the heist, the pounding waves, tires on slick asphalt, the keening gulls, all add to the surreal abstraction.

A black Buick filled with men, its windshield wipers working furiously, pulls up. Carefully timed, several men in trench coats and fedoras enter the branch of the Banque Nationale de Paris (BNP) near closing time. Slipping on their shades before entering, they carefully take their places. A bravura 20-minute sequence, silent save for ambient sounds, detail the meticulously planned heist, and the heroic gesture by a teller that makes it all go wrong. The clinical overhead catalogue of social behavior at the crime scene is like a tragedy choreographed by Tati.

The gang drives off with half the loot and one badly wounded thief. When Simon realizes the cops knows Marc Albouis (André Pousse) is in the hospital, he sends Cathy to dispense with his uncomfortable truth.

In Melville’s world, the criminals proceed with methodical calm. The police seem to function randomly, subject to constant crime calls, informants (for good of for ill). Roughing up suspects during interrogations is the extent of their Method.

Simon’s next caper involves robbing a drug smuggling ring. As the money mover Mathieu la Valise (‘Suitcase Matthew’-Léon Minisini) smuggles the drugs to Lisbon via Bordeaux, Simon’s gang follows the train by helicopter and he calmly lowers himself onto the speeding train, robs the smuggler, and is hoisted back onto the copter, while the police wait at the station. Again Its near-silent sequence, punctuated by ambient noises and one line of dialogue. Melville makes us forget the miniature, as theatre patrons forget painted stage scenary.

Inside the locked train bathroom, Melville records every detail. Simon strips off his climbing gloves, sneakers, jump suit, carefully stores them and dons a dressing gown and slippers and his tools. Only a French director would get so much mileage out of a robber’s accessories. As Simon repeatedly washes the soot off his face and combs back his hair, ready to encounter passers-by in the corridor, Melville builds suspense.

Elegant Delon saves his layering of nuance till the third act, and it’s all there, as delicately limned as an Alec Guiness performance. Disillusion poisons the air he breathes and forces his hand, One betrayal leads to another. Emptied out, he resumes his round with the same numb ritual dialogue.

DP Walter Wottizm’s palette is grissage, a wash of greys and blues. Patricia Neny’s edit works around the aforementioned cost saving decisions.

Melville’s blue grey world is unforgettable. His mute stylish men, who never shy from violence, but don’t messy their lives with it; they are all attitude, glances, action in a terse poetics. A MUST SEE’