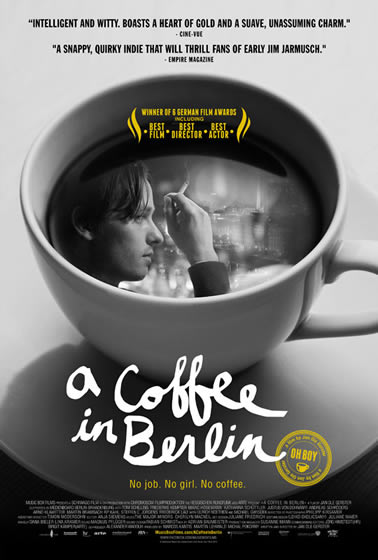

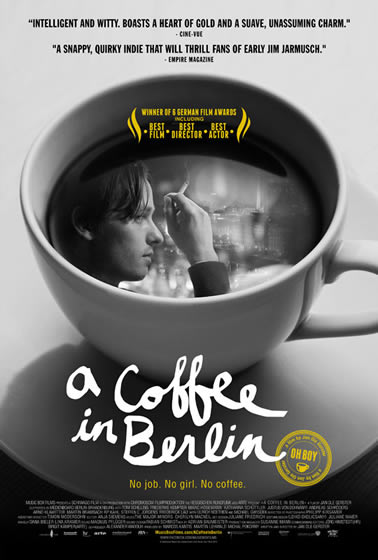

Jan Ole Gerster’s debut feature, “A Coffee in Berlin” (originally titled “Oh Boy”) is another unbe-coming of age flic. Gerster’s thesis project for the German Film and Television Academy, swept the 2013 German Film Awards (unusual for a modest black and white slacker film.

Jan Ole Gerster’s debut feature, “A Coffee in Berlin” (originally titled “Oh Boy”) is another unbe-coming of age flic. Gerster’s thesis project for the German Film and Television Academy, swept the 2013 German Film Awards (unusual for a modest black and white slacker film.

It’s not my sort of film, I found Noah Baumbach’s “Frances Ha” unbearably twee. Nor am I entranced by Gerster’s obvious muses: Jarmush and Allen. I’m bored by Jarmush, (his latest, “Only Lovers Left Alive”, was filled with coy literary and filmic references) and Woody Allen’s post-Doumanian films leave me cold.

The theme of entitled narcissists, unable to commit, has been explored for some decades now. Popularized by Seinfeld (which worked because of its grounding in American comedy tropes) and Larry David’s autobiographical “Curb Your Enthusiasm” (less funny to me) uncommitted characters drive most mumble core pictures.

I prefer my comedy or irony straight up, with context, instead of the context free “post-modern irony”, a stance like the branded “counter culture” outfits popularized in hip magazines. Now everybody’s cool, no personal expression necessary.

A corollary in music would be Norah Jones, whose “jazz-lite” ready-made melancholy substitutes nostalgia for the emotional challenges of Jazz. If Jazz is a cry in the night, Jones’s music is a whimper, a moue.

Or consider the latest in high end dining: expensive comfort food. The bar-friendly menus, overly salted, sugared and fried, seem like fast food made of better ingredients. If the best restaurants of the 90’s offered food that challenged the palette and called on the historicity of food, the current trend seems like a tailgate party.

Writer-director Gerster has a talent for casting, and his off kiltre episodic comedy looks and sounds great. He has an unforced approach to the minutia and absurdities of life.

Tom Shilling is perfect as the hapless Niko, whose worst day is the harvest of his inability to commit to anything. He wakes up at his girlfriend Elli’s apartment. Elli Elli (Katharina Schüttler) tries to pin him down for a coffee date. Reluctant to agree to any plans (“I have a million things to do”) he drives her to break up with him. That’s just the beginning. His rich father cuts him off when he discovers he dropped out of college two years ago. The psychologist (Andreas Schröders) who can help alcoholic Miko get his drivers license back, torments him with Kafaesque bureaucratic tricks and suspend his license.

Passive Niko is surrounded by absurdist characters and encounters. It’s as if he drives everyone to heightened response to fill his vacuum.

The vignettes are linked by a running joke, as Niko attempts and fails to ever get a cup of coffee. I was reminded of the hook from Bunuel’s “The Discreet Charm of the Bourgeoisi .” In Bunuel’s brilliant film, several well-heeled couples attempt, and repeatedly fail, to eat dinner. Each time a surreal event (a death, a possible drug-raid, an act of political revolution intervenes) but the blithe would be diners ignore the radical intrusions. Bunuel also critiques entitlement, but his fierce surrealism depends on historical and political context, which he disrupts with forceful satiric images.

Alas, in 2014, historical and social context is not in favor, watered down but so-called ‘Postmodernism’, globalized dumbing-down and branding.

Like Frances Ha, Niko runs afoul of an ATM. When the machine swallows his card, he tries to steal back the change he gave to a homeless guy.

Visiting his dad at the Golf Course of his Country Club, Niko explains that the ATM ate his card for lack of funds. Why should Pop Fischer (Ulrich Noethen) continue his $1,000 allowance? “Cut your hair, buy some decent clothes and get a job like everybody else,” dad advises before teeing off.

Niko’s neighbor shows up bearing meatballs, but it’s just an excuse for a lonely rant: His wife had a masectomy, he can’t get it up for sex anymore. “They took her whole rack!”, he cries then bemoans her interruptions during his football games.

Niko runs into foxy Julika (Friederike Kempter), only to find out she was his victim in highschool. She spent time at a “boarding school for fat people” to recover from his endless barbs. He called her “Roly Poly Julia”. Don’t worry, she gets her revenge, he suffers through her theatre companies pretentious interminable production. (We’ve all been there.)

Their reunion is marred when some obnoxious teens offer Julika 10 euros to “show us your tits.” Niko freezes but empowered Julika scares them off. He also clinches when they drift towards sex.

He visits his best friend Matze (Marc Hosemann) on the set of a movie. Failed actor Matze, forced to beg for walks-ons, plays the “lead” in a Nazi film within a film. While Matze suffers over his character’s moral dilemmas, Nazi and Juden-extra’s mill behind him, smoking and complaining about the biz. It’s the richest set-up in the film.

In another interesting scene, Niko dozes on a woman’s Barcolounger, while his pal buys drugs from her dealer grandson. It’s the perfect scene to conjure up the carefree timelessness of childhood (Even an extended one like Niko’s).

By the last act it becomes clear that Gerster is digging around to reveal the end resultant of social passivity. The film is laced with the agony of Germany’s past, Nazi themes, skinheads and a haunted Hitler youth.

Alone at a late-nite bar, he meets an elderly, garrulous drunk (Michael Ginsdek) who describes watching his father’s violent thuggery in Kristallnacht, the Nazi first pogrom against the Jews.

Niko actually steps up to the plate in the final scene.

Cinematographer Philipp Kirsamer massages Berlin in elegant monotone shots, capturing vacant lots, the blur of urban traffic and the city at dawn (think Antonioni’s “l’Eclisse.”) The jazz score by Cherilyn MacNeil (Dear Reader) and The Major Minors bridges the scenes.

I’m curious about Gerster’s next film. Perhaps he’ll commit to a more developed story arc. Opens Landmark Nuart Theatre June 27-July 3. Opens,July 2, Regency South Coast Village, Santa Ana and July 4, Laemmle’s Music Hall.