Memoir films – what some have called diaristic or first-person documentaries – have a long and accomplished tradition in independent cinema. Among many standouts, one thinks of Alan Berliner’s ”Nobody’s Business,” (about a recalcitrant father), or Ira Wohl’s classic duet “Best Boy” and “Best Man” (about a challenged family with a severely retarded “man-child”). Other strong examples hail from Lithuanian-born filmmaker and World War II exile Jonas Meklas, whose 70-year film career essentially documents a relentless, lifelong quest to find a place to call home.

Within this diary genre is a sub-genre of what might be dubbed the cancer documentary or cancer memoir, in which sufferers of the disease, or those close to them, turn the cameras onto their own life struggles. In HBO’s Peabody Award-winner “Cancer: Evolution to Revolution” from 2001, filmmaker Joseph Lovett not only chronicled patients battling the disease, but recorded his own kin as they try to cope with the prevalence of cancer in their family.

“I approached the project wanting people to know that they have the ability to deal with their own lives,” Lovett said, “that they could be living with cancer, rather than dying of cancer.”

As Lovett knew, the urgency of these films lies in the inevitable question their subjects must tackle: how can I address the imminence of death? How can I live with cancer and still demand positive options of it, rather than merely dying from it?

Wrestling with such demons, memoir documentaries can emotionally move us beyond their own narratives to arrive, in the best cases, at a kind of catharsis for both filmmaker and viewer.

It’s with this mission that Berlin-based filmmaker Wolf Gremm has completed his own film memoir, “Wolf at the Door,” about his continuing three-year struggle with inoperable bone cancer. Perhaps best known internationally for his feature film “Kamikaze 89,” starring his friend and colleague Rainer Werner Fassbinder, Gremm’s 40-year career has spawned nearly 50 films and telefilms, most of which have been produced by his wife and film partner, Regina Ziegler, and her production company Ziegler Film, one of the most prolific in Germany.

It’s with this mission that Berlin-based filmmaker Wolf Gremm has completed his own film memoir, “Wolf at the Door,” about his continuing three-year struggle with inoperable bone cancer. Perhaps best known internationally for his feature film “Kamikaze 89,” starring his friend and colleague Rainer Werner Fassbinder, Gremm’s 40-year career has spawned nearly 50 films and telefilms, most of which have been produced by his wife and film partner, Regina Ziegler, and her production company Ziegler Film, one of the most prolific in Germany.

“I had lead a turbulent life, totally concentrated on perfection and approval,” Gremm remarks near the film’s opening. “I made one film after the other from 1970 until I exceeded the limits of my emotional and physical capacity.”

Then, in 2011, during production of a new feature, the cancer strikes.

“It tears me up in the middle of my work,” he recalls, “a predatory cancer that attacks with total surprise.” Both the director and his film suffer a sudden, total collapse: “I am heading toward a catastrophe.”

It’s a credit to Gremm’s pluck and optimism that he greets the onset of disease as an opportunity – a call to work and battle. If cancer is going to wipe out his career as he’d known it, the least it can do is furnish him with some positive options – a storyline for a new film, perhaps?

That kind of existential quid-pro-quo stirs a creative impulse that becomes the director’s chief weapon in his fight. Like a cat-and-mouse game, his film plays out in a  loose kind of call-and-response rhythm: As a patient, Gremm is summoned repeatedly to the doctors for more treatment and talk; as an artist, he responds to the summons with flights of visual and narrated memory recorded in multiple formats – filmed, photographed, videotaped, digitized, painted – as he “escapes into the past.”

loose kind of call-and-response rhythm: As a patient, Gremm is summoned repeatedly to the doctors for more treatment and talk; as an artist, he responds to the summons with flights of visual and narrated memory recorded in multiple formats – filmed, photographed, videotaped, digitized, painted – as he “escapes into the past.”

We see scenes of family and career celebrations, interviews with actor and artist friends (including an intriguing clip of a rarely-seen interview Gremm did with Fassbinder, on the night of his death), excerpts of home movies made on location, and clips from his many

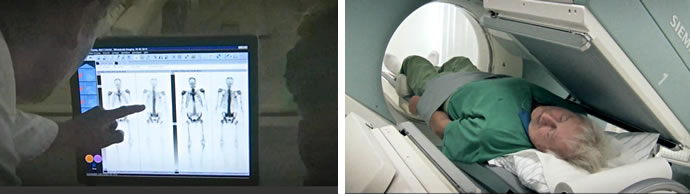

We see scenes of family and career celebrations, interviews with actor and artist friends (including an intriguing clip of a rarely-seen interview Gremm did with Fassbinder, on the night of his death), excerpts of home movies made on location, and clips from his many  German films. All are seamlessly interwoven with the hospital visits and their attendant radium injections, x-ray analyses, MRI tubes, and the faces of his kindly, sympathetic doctors. (Following his wishes, wife Regina even photographs him while he lies, near death, in a 6-day coma.)

German films. All are seamlessly interwoven with the hospital visits and their attendant radium injections, x-ray analyses, MRI tubes, and the faces of his kindly, sympathetic doctors. (Following his wishes, wife Regina even photographs him while he lies, near death, in a 6-day coma.)

Like most memoir documentaries, “Wolf at the Door” is a found film – Gremm discovers it (and himself) as

he makes it. There’s a sense of an almost paradoxical joy of invention and of new opportunity (the “door” of the title) shadowed by gut-punching fear, pain and uncertainty (the “wolf”) that gives the film its emotional backbone.

he makes it. There’s a sense of an almost paradoxical joy of invention and of new opportunity (the “door” of the title) shadowed by gut-punching fear, pain and uncertainty (the “wolf”) that gives the film its emotional backbone.

What results is a clear-eyed and very moving collage that’s alternately wistful, funny, angry, wise, fearless. It all feels completely authentic, almost improvised — a filmic antidote to the trauma playing out in all-too-real time.

“Life is only bearable in memory,” Gremm writes in his notes to the film. “The single, plausible remaining way of making films is to assemble them out of ruins.”

In one poignant scene, shot while visiting Death Valley, Gremm succombs to tears while reading aloud from his journal, then struggles to cope with the frustration of clueless tourists off-camera invading the scene by jabbering about tanning protection. The camera keeps on running throughout, as if to demand that Gremm rescue this private moment. This he finally manages to do, and the honesty and rawness of the scene is unforgettable.

In one poignant scene, shot while visiting Death Valley, Gremm succombs to tears while reading aloud from his journal, then struggles to cope with the frustration of clueless tourists off-camera invading the scene by jabbering about tanning protection. The camera keeps on running throughout, as if to demand that Gremm rescue this private moment. This he finally manages to do, and the honesty and rawness of the scene is unforgettable.

“I thought for a long time whether I wanted to show (this),” he confides in the voice over. “I think it is right that Scott did not turn off the camera.” (The camera here is operated by his friend, the actor Scott Wilson, who clearly has an actor’s instinct for a good scene).

Part of the hard-headed charm of “Wolf at the Door” lies in the director’s obsessive impulse to document himself as an actor in his own

Part of the hard-headed charm of “Wolf at the Door” lies in the director’s obsessive impulse to document himself as an actor in his own  road movie. The film is really the ultimate cinematic “selfie,” with additional footage from nearly everyone in his circle, including his wife Regina, her assistant Markus and Gremm’s assistant and photographer Jakob. Even this writer filmed him on a recent visit.

road movie. The film is really the ultimate cinematic “selfie,” with additional footage from nearly everyone in his circle, including his wife Regina, her assistant Markus and Gremm’s assistant and photographer Jakob. Even this writer filmed him on a recent visit.

(Belated disclaimer: I am a long-time friend of the director and his wife, and assisted with the film’s English narration).

After suffering a near-fatal collapse in Miami, for example, Gremm is loaded onto a Lear jet ambulance to fly home to Berlin (kudos to German health insurance for footing the bill). Never one to let incapacitation get in the way of a good shot, Gremm films the scene  himself from the POV of his hospital stretcher as Markus and Regina accompany him down the tarmac, handycams at the ready. You half expect the patient-director to bolt from his sickbed and request an additional angle. But the coverage pays off with a shot of Regina popping her head into the plane to bid a heartfelt, if hasty, farewell.

himself from the POV of his hospital stretcher as Markus and Regina accompany him down the tarmac, handycams at the ready. You half expect the patient-director to bolt from his sickbed and request an additional angle. But the coverage pays off with a shot of Regina popping her head into the plane to bid a heartfelt, if hasty, farewell.

*

Last February, I visited Gremm in Berlin as he recuperated in a private hospital ward. (“I’ve been checked in to so many, I could do a road movie just on Berlin hospitals.”) Since the cancer arrived, colors have become big part of his life — bright, buoyant colors that celebrate the milestone of simply being alive in this world. It was all part of his “coming out” to cancer, heralding it instead of hiding it.

road movie just on Berlin hospitals.”) Since the cancer arrived, colors have become big part of his life — bright, buoyant colors that celebrate the milestone of simply being alive in this world. It was all part of his “coming out” to cancer, heralding it instead of hiding it.

The year before we had served on a film festival jury together, and Gremm’s electric blue suit was one of my favorite memories (along with a particularly humorous riff on where to attach a morphine patch). Actor Heniz Hoenig has described Gremm as “a big funny kid with a baby face, silver hair and so bizarre,” and it’s a fitting compliment.

The year before we had served on a film festival jury together, and Gremm’s electric blue suit was one of my favorite memories (along with a particularly humorous riff on where to attach a morphine patch). Actor Heniz Hoenig has described Gremm as “a big funny kid with a baby face, silver hair and so bizarre,” and it’s a fitting compliment.

Today, he is swathed in bright orange and green muslin scarves wrapped over a blue shirt, and topped off by a lavender fedora with a pink band.

“Welcome to the land of dead people!” he laughs.

Gremm’s food tray has morphed into a makeshift editing suite, and he is surrounded by handycams, cords, hard drives, script scribbles, a TV monitor.

Disease as a film project.

We spend an hour talking about death. Like a bizarre premonition, the theme of terminal illness plays out in many of the German films of his heyday. Most of them are psychological thrillers, and he’s tucked some of the death-bed scenes into his documentary as well.

Why psychological thrillers?

“Because in that world, there is rarely anything to gain but one’s own life,” Gremm says. “It throws the hero all the way back to his own self, his unworthiness… and he finds his way to a new identity.” He seems to be talking about himself.

“Because in that world, there is rarely anything to gain but one’s own life,” Gremm says. “It throws the hero all the way back to his own self, his unworthiness… and he finds his way to a new identity.” He seems to be talking about himself.

Gremm hands me a colorful spiral-ringed book containing essays, photos, reviews and journals he has artfully compiled from his life and career.

I glance at a few of the film titles — “I Thought I Was Dead,” “Only A Dead Man is a Good Man, ” “I Want to Live,” “Deadly Rendezvous,” “Cliffs of Death.” Talk about a trend. Like a Big End Credit, the subject of death had tracked Gremm throughout his “reel” life, then hunted him down in real life, and now, in his early 70s, had lodged itself once again in his art, through the genesis of this documentary.

” “I Want to Live,” “Deadly Rendezvous,” “Cliffs of Death.” Talk about a trend. Like a Big End Credit, the subject of death had tracked Gremm throughout his “reel” life, then hunted him down in real life, and now, in his early 70s, had lodged itself once again in his art, through the genesis of this documentary.

“I’ve finally become a character in my own film noir!” he muses, savoring this bit of dramatic irony.

Before I leave, Gremm insists on showing me some of his rough cut. On the monitor, his “character” stares back at the camera in a hospital gown and from a different bed. He’s hooked up to oxygen tubes and looks ghostly, feeble, confused. He’s mumbling something into his ubiquitous handycam. It’s all in black and white.

Gremm watches himself, fascinated. We’re reviewing the film’s opening sequence, in which he has awoken from his coma following his collapse in Miami.

“Look at this! The coma was more real to me than reality. I had hallucinations, horrible nightmares. I imagined I was on a plane kidnapped by government agents trying to kill me!”

He laughs. But frankly, it all seems a bit much to me — this obsession with watching and reliving your own demise. Why spend whatever time you have left in this world burrowing into a black hole?

Then he presses the fast forward button.

In a few moments I see a freeze-frame of a kindly young man dressed in a brilliant orange and red robe. He has a shaved head and a huge smile. He’s holding both hands of a gaunt Gremm, who’s in a hospital gown, still tethered to his tubes and wires.

The man is a Tibetan monk who happened to be in Miami, and whom Gremm asked to meet after waking from the coma. In the frame, Gremm smiles softly at the man, who beams at the camera. I can sense that some kind of awareness, even joy, has just been shared between them.

Gremm stares at the screen in silence.

“After this meeting, I began to believe in life again. In even the briefest moments of happiness. You know, the little gifts.”

He wipes an eye, “Like when Regina bought me a barbell!”

I realized then what had moved me most about Gremm. It wasn’t just his battle with all the fear and despair, or even his humor in fighting it. It was what he’d  learned from the disease, and his honesty as a filmmaker in sharing that with others, especially fellow cancer patients. “Hopefully, I can give some of you out there who are hanging onto life like me some of my optimism, which I’ve always had,” he tells us in the film. It’s the peace and clarity he’d managed to rescue from that black hole.

learned from the disease, and his honesty as a filmmaker in sharing that with others, especially fellow cancer patients. “Hopefully, I can give some of you out there who are hanging onto life like me some of my optimism, which I’ve always had,” he tells us in the film. It’s the peace and clarity he’d managed to rescue from that black hole.

If Gremm were making one of his TV thrillers, this might be where he’d put the end credits — the part where the hero succeeds in saving his own life. For now.

But “we humans are like the stars,” he tells us at the film’s close. “Our light continues to shine, even after we are no longer alive.”

It shines through film, too. Exiled by disease just as the filmmaker Meklas was by war, Gremm has ventured to find “home” by making the movie of a lifetime. You can’t ask more from any memoir than that.

* * *