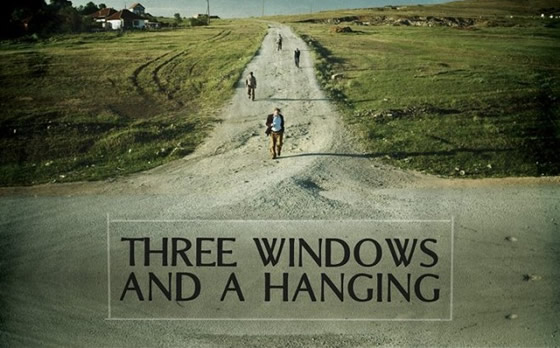

Isa Qosja’s restrained drama “Three Windows and a Hanging” (Tri Dritare dhe një Varje) is Kosovo’s first-ever Foreign Oscar Submission.

Isa Qosja’s restrained drama “Three Windows and a Hanging” (Tri Dritare dhe një Varje) is Kosovo’s first-ever Foreign Oscar Submission.

Veteran director Isa Qosja (“ojet e mjegulles”, “Proka”) tackles a tough subject, the rape of women by Serb forces during the 1998-99 Kosovo war, and the traditional culture’s inability to accept a woman who’s been “sullied.”

Qosja’s 2005 award-winning blackly comic “Kukumi” was the first film from Kosovo since it was declared a UN-protected “mission”.

The film, set in the fictional mountain village a year after the 1999 war, examines the inflexible issue of “honor” in Kosovo’s patriarchal Albanian society.

The film feels light in the first act, as the script introduces the small cast of villagers. It’s book-ended by two comic sequences in which three elders sit under an ancient spreading tree, and like a folk-tale, argue about which version of the story is true.

Big-shot mayor Uka (Luan Jaha “The Forgiveness of Blood”, “Time Of the Comet”) lords it over the mountain village. His shop dominates the center of town. From the tables out front one can see anyone approaching the remote community. Blowhard Uka even takes credit for the Swiss-donating cows grazing everywhere.

While Uka pontificates to the men smoking and drinking coffee outside, his hollow eyes wife (Aurita Agushi) scurries around compulsively cleaning, and their comely daughter Drita (Doresa Rexha) minds the store. Drita is being courted by a gangly teen motorbike rider who Uka runs off his property.

Local schoolteacher Lushe (Irena Cahani) gives an interview to a foreign journalist, “betraying” a well-kept secret- she and three other local women were raped by Serbs during the conflict, just three days before the Nato bombing.

The news runs through the closed community like a tsunami, the drama darkens and before the tale is done a sea change has occurred.

Other women are seen in the background. Unlike Uka’s housebound family, teacher Lushe (still waiting for her husband Ilir to return after the war) has taken on the full responsibility of raising their son.

Lushe runs the local school, and does all the maintenance and heavy lifting around her home. The men in the village are uncomfortable around the war ‘”widow”, an outsider who married a local.

Once the newspaper reaches the village, Uka’s wife blames Lushe, alluding to a secret that haunts their family. Craven Uka kept the secret shame of his raped wife to himself, and she kept his ugly secret as well, in order to maintain their high status in the village.

Sympathetic husband Sokol (Donat Qosja-‘Kukumi’) dotes on his morose wife Nifa (Leonora Mehmetaj). He simply doesn’t understand her changed personality. Doubt eats at him and he asks Uka about the article. Tired of being questioned by locals Uka bursts out, “Go home, ask your wife.” Unable to express his feeling, Sokol confronts his wife. She suicides.

Villagers are quick to suspect the outsider. Uka tries to deny the rapes to protect his family’s shame but eventually outs Lushe as the whistle blower, starting the men wondering whose wives were ruined.

Trying to ostracize Lushe, they pressure her to move out of town with her son. In an eeiry scene; scapegoated Lushe enters the bar, the only woman there, and asks for a drink.

The villagers pull their kids out of school, other kids grill her son about the rape, but Lushe refuses to be run out, in case her husband reappears.

Narcissist Uka gets his comeuppance. Drita runs away with her sullen motorbike swain and his wife forces him to acknowledge his wartime act of cowardice, if only to himself.

Ilia (Basri Shala) returns from a prisoner of war camp. The locals pressure him to abandon Lusha, but Ilia becomes an agent for change, urging the other men to apologize to the war-victims.

Qosja avoids wartime flashbacks or accusations. He’s more interested in showing the toxic effect of traditional patriarchy, on display in playwright Zymber Kelmendi’s nuanced script.

Uka’s secret shame (he watched the rape while hiding from the local “police”), and Sokol’s inability to talk with his wife increase the tragedy. Seeming strong is everything in this culture; there’s no room to love nor to protect the women close to you.

Women who are raped aren’t seen as war-victims, they are spoiled women to be ostracized, punished for revealing their secret shame. Male honor trumps morality, compassion and emotional bonds.

Produced by actor Shkumbin Istrefi (“Kukumi”, “Donkeys Of The Border”) for a mere $810,000, the drama reflects the tensions between traditional Balkan rural customs and urban “international” social values.

Turkish DP Gökhan Tiryaki, a long time collaborator of Nuri Bilge Ceylan ( “Winter Sleep”, “Once Upon A Time In Anatolia”, “Three Monkeys”) sets the tragic story among dark, shadowed interiors. Landscape shots capture the dry rural setting. The near empty village roads give an indelible sense of place and the feel of a classic Western revenge tragedy.

Avoiding a score, the silence, which permeates the scenes, adds to the sense of rural isolation.

Kosovo authorities say up to 20,000 women may have been victims of rape at the time. Rape was used as a weapon of Mass destruction and ethnic cleansing. Paramilitaries and masked Serb neighbors searched villages for girls of prime, childbearing age.

After the war, If the rapes were revealed, traditional values forced the families to shun and expel the “touched” women, less the rape shame the relatives. Women gave up the children of rape, and in some cases killed them or themselves.

The Republic of Kosovo declared their independence from Serbia in 2008. Serbia rejects Kosovo’s independence, however there is increasing dialogue between the governments of Kosovo and Serbia.

Winner Cineuropa Prize, Sarajevo, 2014. SEEN EFP-LA SCREENINGS