ANTALYA, Turkey — You wouldn’t think a film festival situated only 500 miles from war-torn Syria – and that opens only six weeks after a major terrorist attack in its country – would have the gumption to invite a bunch of Hollywood stars to help celebrate itself. At least, not if it expected to get any takers.

But that’s exactly what Turkey’s largest and oldest film forum, the Antalya International Film Festival, managed to pull off during a star-studded and hectic week last December.

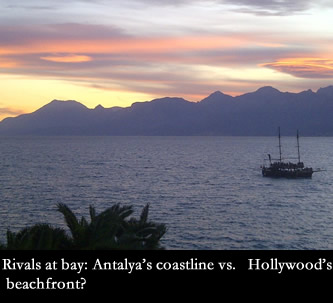

Located on a spectacularly cinematic stretch of Turkey’s south Mediterranean coast, with enough lumens of key light to satisfy any celebrity, the 52-year-old festival played host this year to such Euro icons as Catherine Deneuve, Jeremy Irons, Vanessa Redgrave and husband Franco Nero (all four of whom received lifetime achievement awards), along with Hollywood stars Kathleen Turner and Mena Souvari.

Located on a spectacularly cinematic stretch of Turkey’s south Mediterranean coast, with enough lumens of key light to satisfy any celebrity, the 52-year-old festival played host this year to such Euro icons as Catherine Deneuve, Jeremy Irons, Vanessa Redgrave and husband Franco Nero (all four of whom received lifetime achievement awards), along with Hollywood stars Kathleen Turner and Mena Souvari.

They all clearly relished the requisite blaze of photo ops, lavish beach luncheons and glitzy awards-doling that has become the Levantine’s answer to Cannes’ Croisette. And none of them seemed too worried about security.

“My dear, I was sitting outside at a Paris café just a couple of days after the (ISIS) attacks,” Deneuve told me during a festival lunch. “I am not one to be inhibited by all this, so I don’t listen to the paranoia marketed on all the news shows. Life goes on. I am very happy and not at all nervous to be here.”

Irons added that “once you arrive here you see how disproportionate the fear is that tends to overtake people back home. Turkey is a delightful place and the people are famously hospitable. I didn’t blink twice at coming.”

It didn’t hurt, of course, that the stars received very handsome appearance fees to attend, thanks to the festival’s budget of 17 million Turkish lira (US $5.6 million), about 10% of which went to star-wrangling and star fees, according to the festival. (The security budget, which was not provided, is not included in this amount.) Or that Antalya had played host two weeks earlier to the G20 world economic summit – held in the shadow of the ISIS attacks – with its brigade of 30,000 police and security personnel. Presumably that meant the fest’s smartly dressed security detail had been well-rehearsed.

attacks – with its brigade of 30,000 police and security personnel. Presumably that meant the fest’s smartly dressed security detail had been well-rehearsed.

“Nevertheless, security was a huge concern this year,” noted Elif Dagdeviren, the festival’s charismatic artistic director who doubles as a successful film producer. “Before the festival I was getting emails not only from celebrities but from directors and writers – everyone was so scared.” (Turkey had also been put on the U.S State Department’s Alert List).

The festival did spend a good deal of time and effort reassuring guests that yes, in fact, Antalya had just hosted the likes of Putin and Obama and their entourages, along with a bevy of Saudi princes, and nothing went awry there.

“Then those same celebrities and guests would say to me yes, fine, but their security staff will be gone and we’ll be stuck with your security!” remarked Dagdeviren. “But actually, our festival security comes from the CIA, the Mossad and the KGB. They work for them. Our security is their security.”

Turkey, it seems, has long been accustomed to straddling the fault lines of East-West geopolitics when it hosts western visitors. The festival’s military-trained detail of several hundred security workers were nearly invisible to the 1,800 invited guests and 25,000 visitors. So much so that Dagdeviren herself wasn’t always aware what they were up to.

“I found out only after the festival that in every screening session, we placed plainclothes policemen in the audience, and they acted as viewers,” she said. “Police dogs were brought in each day and they silently sniffed the theatres before we could let people in, which is why some of the screening starts were delayed. That kind of security action never happened before in any of our festivals in Turkey.”

Still, when Turkish terrorist attacks rock the media as they did last July in Suruç and October in Ankara, not to mention the post-festival suicide bombing near Istanbul’s Blue Mosque in January (which, I reflect, happened just 100 yards from the boutique hotel where I had stayed three weeks earlier), it seemed extraordinary that Dagdeviren and company could so discreetly and effectively handle the most worrisome elephant in the room.

*

I had been invited to Antalya to serve on the Festival’s National Competition Jury, as a last-minute replacement for another American journalist who apparently did succumb to security jitters. (My thanks to the tireless publicist and festival consultant Nichola Ellis for this lucky substitution).

I was happy to discover that jury members were treated rather like celebrities themselves, feted with sumptuous luncheons at 5-star restaurants and each accorded (or at least I was) his own personal chauffeur and a personal assistant. It all came with a fabulous suite and equally fabulous panoramas of the shimmering Mediterranean, cradled at the feet of the majestic snow-capped Taurus Mountains. Cannes lovers should weep.

All of which made the jury schedule of 2-3 screenings a day far less onerous than I imagined, with one exception. Quite of few of the Turkish entries suffered from a somewhat recent but unfortunate cinematic tradition: an indulgence in long, ponderous shots of pointless mundane activity (dishwashing, butter-churning) that go on and on…and on.

“Tell me Ömer,” I asked our dapper and delightful jury president, Ömer Vargi, himself a producer of over 400 films and the head of Istanbul Film Studios. “How many more scenes will we have to watch like that tundra film with the peasant on the horizon who spends 5 full minutes walking toward the camera to collect his yak? Or the scene of the father waiting for an office elevator to arrive from the 10th floor to the lobby. And then he steps inside and the doors close and it goes up again and the camera is still running.”

I exaggerated of course. It was probably only 1 minute of walking and 3 floors of waiting. But it seemed like an eternity, because unless the director happens to be a Tarkovsky or an Antonioni, both of whom knew very well how to make long, static shots feel neither long nor static, it always is an eternity.

I exaggerated of course. It was probably only 1 minute of walking and 3 floors of waiting. But it seemed like an eternity, because unless the director happens to be a Tarkovsky or an Antonioni, both of whom knew very well how to make long, static shots feel neither long nor static, it always is an eternity.

“Yes, I have a theory,” Ömer replied between cigarette puffs. “I think some of our filmmakers have fallen in love a bit too much with the French auteur style and are still trying to imitate it.” (Ömer was one person I’d gladly suffer second-hand smoke from to hear his theories.) “It’s like a dream some of them can’t quite snap out of. A bad dream for some people!”

Luckily, my fellow jurors mostly agreed on which of the 12 films in the Turkish competition were the most artistically “awake”. (For the record, my cohorts also included Turkish actresses Şerif Sezer and Şebnem Bozoklu, Bosnian cinematographer Mirsad Herović, director Naz Erayda and screenwriter Tarık Tufan). We handed the film “Ivy,” a Sundance 2015 entry written and directed by Tolga Karaçelik, the festival’s Golden Orange Award for Best Picture. Inspired by the stories of Melville, it’s about a stranded container ship bound for Egypt whose broke and hungry crew ultimately turn on themselves as they turn their ship into a war zone of petty betrayals and intrigues. I could certainly see this film crossing over to international audiences. We also gave best directing and screenwriting honors to Karacelik, which was an easy call for most of us.

But it was the film’s lead actor, Nadir Sarıbacak, who for me was the standout talent of the national competition. His Best Actor award was one of the quickest picks in our final 3-hour jury session.

*

Antalya harbors high and well-founded hopes for becoming a film and arts mecca in the Middle East. Along with the film festival, the city already hosts a major international piano competition every autumn. Mayor Menderes Türel, who himself is an accomplished pianist and a former journalist, told me he was wooing “a major Hollywood studio” to help spawn a massive new production complex o the city’s outskirts.

“Actually, the angle and quality of the light here is very much like Los Angeles,” he said over lunch, his arm describing an arc across the panoramic coastline below, a view that admittedly upstaged Santa Monica Bay. “We already have a record 13 million visitors a year, so we are well set to be the world’s window to the Eurasian market.”

view that admittedly upstaged Santa Monica Bay. “We already have a record 13 million visitors a year, so we are well set to be the world’s window to the Eurasian market.”

That window comes with a lot of expensive dressing. There’s a $500 million proposed budget that covers film studios, exhibition space, and a film university. The Antalya municipality will also chip in an additional $20 million for a new film palace that Türel insists “will be even bigger and more impressive than the Palais in Cannes.” Which, I suggested, wasn’t too high a benchmark to surpass.

*

Besides concerns for security, the other shadow hanging over Antalya this winter was the dearth of overseas visitors. Normally this place is a tourist mecca, with shiploads of shoppers puttering through the old =town’s quaintly cobbled streets, eyeing the stalls of bric-a-brac bronzes and technicolor textiles and the heaps of opalescent spices. They crowd the city’s vest-pocket harbor that’s guarded by rambling Roman ruins, views of which are frustratingly framed by the Miami Beach-style hotels rimming the sea.

But hardly anyone was buying this year. When I finally stole a chance to stroll the markets after my second day of screenings, I was actually happy to run into the odd carpet seller cheerfully hustling me for a bargain. Occasionally even the street cleaners seemed upbeat; one morning, I walked past a garbage truck playing Mozart.

Still, an air of resignation hung stubbornly over these market folk. All the jaunty bickering and beckoning that plays tag in most bazaars was sucker-punched here, down for the count on a maze of quiet streets. It all seemed more doleful whenever the loudspeakers on the corner mosques droned their ezon, the Islamic call to prayer.

Still, an air of resignation hung stubbornly over these market folk. All the jaunty bickering and beckoning that plays tag in most bazaars was sucker-punched here, down for the count on a maze of quiet streets. It all seemed more doleful whenever the loudspeakers on the corner mosques droned their ezon, the Islamic call to prayer.

The shopkeepers and shoe-shiners managed to make the best of it. At least there was more time for them to enjoy their customary tea breaks and frequent, random acts of cat-shooing. (There are more cats than tourists in this town.)

*

One afternoon, following our morning jury screenings and in a moment of brazen hospitality, my driver Antin (trained by the Turkish army) told my assistant Rama Akyer that he would be “so happy” to drive us out for a “very nice day trip.”

Whereabouts? I asked Antin. I had been hoping to check out a few of the local tourist sights.

“How about Syria?”

Syria??

But Antin insisted there would really be no worries; he always carried an army-issued Kalizhnikov in his black Mercedes van. It would take 7-8 hours each way since it was a 500-mile trek, due east. It would be a “rather long” day trip.

“There are, however, a few kilometers around the border that we might try to avoid,” he noted. “To be on the safe side. Some risk of kidnapping.”

Suffice to say I considered Antin’s kind offer for a millisecond or two. And politely declined.

But I admit that the bragging rights back in Santa Monica were tempting.

*

I had a few favorite jury moments, along with many lingering after-hour chats in the hotel bars and cobblestone cafes.

One of my favorite fellow jurors was Mirsad, the Bosnian DP who has shot a number of hit Turkish movies and whose film “Pop a Revolution” is being produced by festival director Dagdeviren. During a break after one of our screenings, Mirsad reached into his pocket and opened up a photo on his cell phone.

It showed a Balkan worker standing in a field and holding up a pitch fork, with what looked like an iPhone stuck on the top of its middle prong.

“So what do you call that?” I asked him.

Mirsad grinned: “Bosnian selfie stick!”

We agreed this might be an ingenious strategy for him to cut down on the camera budget of his next project.

*

Antin, meanwhile, did manage to stand by his offer and take me out on a day trip. Only not in too easterly a direction, he assured me.

Antin, meanwhile, did manage to stand by his offer and take me out on a day trip. Only not in too easterly a direction, he assured me.

Following breakfast at one of the hotel’s sumptuous, overstocked buffets (crabs, shrimps, caviar, organic omelettes, racks of cheeses, stacks of olives, sausages, breads, patés, flambés, stews, jams, porridges, bowls of spices, tables of fruits, pyramids of desserts), I idly asked Rama if there were perhaps any destinations – westward – we might want to explore before my evening jury screening?

=Minutes later, the black Mercedes van pulled up. Out popped a suited-up Antin, and soon the four of us – the fourth being a delighted Nichola Ellis – were off to sample the glories of ancient Turkey. Among them was the vast amphitheatre of Aspendos next to a mountainside stacked with cave dwellings, and a grizzled old local whose hired boat chugged us to the Roman remains of a sunken city. It glistened under the turquoise waters. We sipped the finest instant Nescafe on a mahogany deck and soaked up the Mediterranean sun.

Who the heck named this jury “duty” anyway?

Not so relaxing was the half-hour race back to Antalya to catch the night’s screening. As we dashed along the coast at dusk with our alarm lights flashing, it was clear Antin’s gig driving for Putin’s entourage had paid off. We arrived at the exhibition hall only five minutes late – and with everyone intact. Two officials greeted us at the steps and whisked us to our seats. Apparently the festival had kept the packed house waiting just for me, a tardy juror.

*

The festival’s final awards ceremony was hosted in a huge glass pyramid that proved to be more cavernous than the Oscar’s Kodak Theatre, and nearly as glitzy.

Elif’s gown was a knockout. Franco Nero came onstage to laud his wife, Vanessa Redgrave, for being “the greatest actress on the planet.” Deneuve made an appearance to either give or receive another award, I can’t remember which. A few honorees managed to bump into a few presenters, inciting a traffic snarl on national TV (oh, for a good stage manager). But like that other elephant in the room, it wasn’t really a problem.

Elif’s gown was a knockout. Franco Nero came onstage to laud his wife, Vanessa Redgrave, for being “the greatest actress on the planet.” Deneuve made an appearance to either give or receive another award, I can’t remember which. A few honorees managed to bump into a few presenters, inciting a traffic snarl on national TV (oh, for a good stage manager). But like that other elephant in the room, it wasn’t really a problem.

My other favorite moment? Hopping onstage in my best (on sale) Armani Exchange outfit to announce one of the winning actors. Under the glaring lights and canned orchestra music, I somehow managed not to flub the Turkish name.

It was a lucky cap to an 8-day trip that, more than anything, had put my old fears to rest and new friends in my life. I could see Mirsad snapping away from our second-row seats.

Then he put down his phone, checked out the photo, and gave me a big thumbs up.

Photos by James Ulmer