Russia’s political image as the “sleeping” bear on Europe’s borders may seem maddeningly oxymoronic following its recent military forays into Ukraine and Crimea. But its images in cinema — seven decades of them since the death of Stalin — are being heartily welcomed this fall by one of central Europe’s most inventive vest-pocket festivals, located next door to the Bear’s newly-made Crimean lair.

Romanian director, writer and producer Radu Gabrea has announced that his annual Medias Central European Film Festival (MeCEFF), based in the central Transylvania town of Medias and curated around a different national cinema each year, will launch its 6th edition from August 30-September 3 with “The Year of Russian Cinema.” The forum will screen over two dozen films by Russian masters, including a retrospective of Andrei Tarkovski, to accompany its traditional competitive program of award-winning movies from seven Central European countries, along with this year’s invited ‘guest’ country, Russia. (Hence the festival’s motto “7+1”)

Romanian director, writer and producer Radu Gabrea has announced that his annual Medias Central European Film Festival (MeCEFF), based in the central Transylvania town of Medias and curated around a different national cinema each year, will launch its 6th edition from August 30-September 3 with “The Year of Russian Cinema.” The forum will screen over two dozen films by Russian masters, including a retrospective of Andrei Tarkovski, to accompany its traditional competitive program of award-winning movies from seven Central European countries, along with this year’s invited ‘guest’ country, Russia. (Hence the festival’s motto “7+1”)

“These are all extremely important films in world cinema, most of which  were made after the death of Josef Stalin in 1953,” the director reported by phone from his office in Bucharest. “In Stalin’s time the main theme in Russian cinema was World War II, which was seen as the great war defending their country. I’ve now decided to jump ahead for a different perspective, to the post-Eisenstein, de-Stalinization era and the arrival of the modern Russian Cinema.”

were made after the death of Josef Stalin in 1953,” the director reported by phone from his office in Bucharest. “In Stalin’s time the main theme in Russian cinema was World War II, which was seen as the great war defending their country. I’ve now decided to jump ahead for a different perspective, to the post-Eisenstein, de-Stalinization era and the arrival of the modern Russian Cinema.”

The new program is meant to complement thematically last year’s MeCEFF festival, which focused on the early and mid-century filmic legacy of World War I. More incidentally, it will also counterpoint the West’s prevailing tendency to put in a negative context “almost anything coming out of Russia these days,” Gabrea said.

“There was a total change after World War II in the subject matter and style of Russian films, which had been subject to strict Communist censorship for years,” Gabrea noted. “Russian movies took on more humane and relatable stories.”

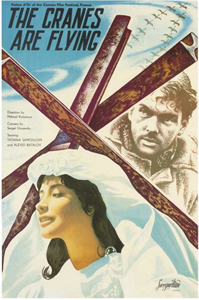

One such film screening at MeCEFF is the Soviet feature “Cranes Are Flying,” which won the Cannes Film Festival’s Palme d’Or in 1957 for

Georgian-born Soviet director Mikhail Kalatozov’s depiction of the Soviet psyche and culture in the aftermath of World War II. Also berthed in this year’s Russian program are Vladimir Menschov’s Oscar-winning “Moscow Does Not Believe in Tears” and Nikita Mikhalkov’s “Oblamov,” both released in 1980, along with the critically-acclaimed entries “Moscow Laughs” (1934) by

Georgian-born Soviet director Mikhail Kalatozov’s depiction of the Soviet psyche and culture in the aftermath of World War II. Also berthed in this year’s Russian program are Vladimir Menschov’s Oscar-winning “Moscow Does Not Believe in Tears” and Nikita Mikhalkov’s “Oblamov,” both released in 1980, along with the critically-acclaimed entries “Moscow Laughs” (1934) by  Grigori Alexandrov; Grigori Chukhrai’s “Ballad of a Soldier” (1959); Karen Shakhnazarov’s “Ward No. 6 (2009);” and the section’s newest entry, “Road to Berlin” (2015) by Sergei Popov.

Grigori Alexandrov; Grigori Chukhrai’s “Ballad of a Soldier” (1959); Karen Shakhnazarov’s “Ward No. 6 (2009);” and the section’s newest entry, “Road to Berlin” (2015) by Sergei Popov.

Comprising the 5-film Tarkovski retrospective are his “Solaris” (1972), “Andrei Rublev” (1966), “Stalker” (1979), “Ivan’s Childhood” (1962) and “Zerkalo” (1975). This year there will also be two guests from the Russian studio Mosfilm invited to discuss Russian cinema.

“My reaction when I saw all these films again was incredibly enthusiastic, even if our relations with Russia are hardly perfect,” observed Gabrea, who frequently veers into politics when discussing cinema. “I am not one to be influenced by Putin’s opinions. I’m not impressed by his menacing actions in Central Europe. And I don’t believe he has as much power now as he had before.”

* * *

Recently, politics has been on Gabrea’s mind more than usual, especially the fraught politics of the Romanian film industry. As one of the country’s grand seigneurs with a career spanning five decades and dozens of internationally recognized films (he garnered the prestigious Knight’s Cross from the German government in 1997), the director now finds himself fighting more and tougher battles in his home country in order to raise the funds – for both his festival and his films – and to secure greater recognition from the younger generation of Romanian film professionals.

He is a passionate and outspoken critic of some of the policies and officials of the country’s film sector, which he contends is in continuous crisis. There is, for instance, the notable sore spot of the Transylvanian International Film Festival (TIFF), McCEFF’s more established and better funded rival located in the city of Cluj and headed by filmmaker Tudor Giurgiu and Mihai Cirilov.

“TIFF ignores my movies, and it’s supposed to be a festival supporting Romanian film,” Gabrea said over lunch at November at Seattle’s Second Romanian Film  Festival, where he and his wife, the Romanian theatre and film actress Victoria Cocias, were invited to screen several of his works, including Goldfaden’s Legacy and the recent “Lindenfeld, a Love Story“, starring Cocias. “Of course every festival needs new blood, and they’re not interested in promoting old guys like me. But without being seen by international journalists, no one will know my films.”

Festival, where he and his wife, the Romanian theatre and film actress Victoria Cocias, were invited to screen several of his works, including Goldfaden’s Legacy and the recent “Lindenfeld, a Love Story“, starring Cocias. “Of course every festival needs new blood, and they’re not interested in promoting old guys like me. But without being seen by international journalists, no one will know my films.”

Another bête noir for Gabrea is government film funding – a spigot that releases only a trickle of money for his festival but whose mechanics, ironically, he helped create.

From 1997-1999, Gabrea was president of Romania’s National Office for Cinematography, where he helped author one of the major film laws that produced the Cinematographic Fund to finance Romanian film. That fund, which he insists is not politicized, still continues today but “in a crisis mode, like the rest of our film industry.”

As for Romania’s Cultural Ministry? “It’s incredible to me that this Ministry gave us nothing this year – zero – and then turned around and gave 500,000 euros to the TIFF festival,” he lamented. For the past five years, he noted, the Ministry had chipped in 25,000 euros annually to MeCEFF, “which is still 20 times less than TIFF.” This year, the Ministry “wouldn’t even let me meet with the person in charge.”

At least the city of Medias and its mayor, who is a strong support of MeCEFF, upped their ante this year and delivered a purse of 32,000 euros for the Festival. And the Romanian Cultural Institute, for which Gabrea has high regard, pitched in 8,000 euros, with some local gas companies and businesses contributing, too.

Gabrea, who is 79, continues to fight some medical battles as well. Last year, immediately following a major operation that prevented him from attending most of his own festival, a frailer but determined Gabrea commandeered a 5-hour car ride from Bucharest to arrive at Medias just in time for the closing night ceremony – and to receive a rousing standing ovation.

At his side, as always, was the dedicated and popular Cocias, who herself manages to negotiate a busy theater and film career while co-running the festival. (Last  year she won best actress honors for Lindenfeld at Bulgaria’s Varna International Film Festival.)

year she won best actress honors for Lindenfeld at Bulgaria’s Varna International Film Festival.)

And still, the seemingly tireless Gabrea continues to make movies.

There’s “Piano in the Mist,” currently in production and his third feature penned by the German writer Eginard Schlattner, who also wrote Gabrea’s “Beheaded Rooster” and “Red Gloves.” Set in 1948, it’s a road movie and love story about a young Romanian girl and her Saxon boyfriend as they travel from the Medias to eastern Romania’s Danube Delta, where her family is forced to live in a Communist work camp.

The movie’s budget of about 1 million euros is expensive by Romanian standards, and predictably, Gabrea is battling to raise more financing. Only about half the film is shot, and every few months the director steals away from Bucharest to shoot more scenes as often as his health and the funding hustle allows.

Following the MeCEFF festival last year, where this writer served as jury member, Gabrea and friends escorted me on a long drive east to visit some of the most lush and serpentine locations of the Deltas rivers and swamp. Early viewings of the rushes, which we watched back in Bucharest, promise a visually lyrical tale.

There is also his ongoing documentary about the life of the Romanian Jewish Communist leader Ana Pauker, who became the country’s first female Minister of Foreign Affairs and, according to Gabrea’s documentary, was one of the world’s most powerful – and misunderstood – women when she made the cover of Time in 1958, two years before her death from cancer.

“I’m making this film because I am interested in debunking myths,” Gabrea explained in between screenings in Seattle. “The myth is that Jews like Pauker brought Communism to Romania, which is ridiculous. But then Romania is a country in which its history is stupidly mythicized. Everything becomes heroic in our history, because after years of Communist occupation and decades of fear people think it’s better not to tell the truth. Maybe it’s the complex of a small country, but we don’t have the right to have that complex.”

“I’m making this film because I am interested in debunking myths,” Gabrea explained in between screenings in Seattle. “The myth is that Jews like Pauker brought Communism to Romania, which is ridiculous. But then Romania is a country in which its history is stupidly mythicized. Everything becomes heroic in our history, because after years of Communist occupation and decades of fear people think it’s better not to tell the truth. Maybe it’s the complex of a small country, but we don’t have the right to have that complex.”

When that older generation dies out, Gabrea argued, such attitudes may “hopefully” vanish as well. “But if you don’t know and understand your own country’s history, you will ultimately make the same mistakes – both in your life as an individual, and your life as a nation. That was Ana Pauker’s great lesson for Romania to learn: simply to tell the truth.”