We’ve just finished eighteen years of showcasing Nordic films—and now Baltic films as well—bringing our audience “top films from the top of Europe” with the outstanding work of filmmakers from Denmark, Finland, Iceland, Norway, Sweden, and Baltic neighbors—Latvia, Lithuania, and Estonia. The festival ran for two week-ends in January at the Writers Guild Theater in Beverly Hills. Our closing film of the 2017 festival was the poignant story from Norwegian World War II history told in Erik Poppe’s film “The King’s Choice.” (The film screens this month at the Berlin Film Festival.)

In the course of eighteen years of SFFLA, films that tell 20th century stories of war years in Europe and the aftermath would often elicit responses from audience members with first-hand memories of those times. Some years ago after we screened the excellent Finnish film “Mother of Mine”—about a boy who was sent away from Finland to the safety of a farm in Sweden during the war, a dignified older Finnish man who was a regular at the festival came up to me with tears in his eyes, took my hands in his and said “Thank you. Thank you. That’s my story. I was one of those kids. Thank you for telling my story.” It was Director Klaus Häro who had told the story so beautifully. The next year the man wasn’t at the festival and I learned that he had passed away. But “his story” had been told (even though it was about someone “like” him who had undergone the trauma of displacement. And the story was preserved. In the brevity of time, eye-witnesses to history are too soon gone—but film preserves the stories. And in the telling—the story continues in the discussions that ensue and memories that are stirred.

In the course of eighteen years of SFFLA, films that tell 20th century stories of war years in Europe and the aftermath would often elicit responses from audience members with first-hand memories of those times. Some years ago after we screened the excellent Finnish film “Mother of Mine”—about a boy who was sent away from Finland to the safety of a farm in Sweden during the war, a dignified older Finnish man who was a regular at the festival came up to me with tears in his eyes, took my hands in his and said “Thank you. Thank you. That’s my story. I was one of those kids. Thank you for telling my story.” It was Director Klaus Häro who had told the story so beautifully. The next year the man wasn’t at the festival and I learned that he had passed away. But “his story” had been told (even though it was about someone “like” him who had undergone the trauma of displacement. And the story was preserved. In the brevity of time, eye-witnesses to history are too soon gone—but film preserves the stories. And in the telling—the story continues in the discussions that ensue and memories that are stirred.

There were others as well – like the Swedish Academy Award nominated film “Evil” in 2003 from Director Mikael Hafstrom set in an elite boarding school in the 1950’s and exposing violence, cruelty, bullying, and dominance and the hierarchies that perpetuate such behaviors and protect perpetrators. One Swedish person in the lobby said “That was exaggerated—they never would have gotten by with that.” Another responded, “My father went to that school and he said that’s exactly what went on.” After “The King’s Choice” and elderly woman said to me “That was hard to watch because I lived through all that. We had an illegal radio and I remember my family and friends gathering around it to try to get news about what was happening.”

Films tell the stories that either haven’t been told, or stories that need to be retold so they won’t be forgotten. And some stories just entertain and hearken to a creativity that goes back to stories told in the light and shadows of firelight. And the truth is that 18 years after the first SFFLA, some of the people whose stories we were telling aren’t around any more. But the films remain to represent.

We’ve filled in the gaps of history. The Oscar nominated Danish film “Land of Mine” tells the story of young teenage conscripted German soldier-boys who are POWS after the end of WWII who are made to dig out landmines with their bare hands. It is such a brilliant discussion of nationalism and how it’s possible to be “on the right side” but lose one’s humanity. It’s also possible to reclaim it. A number of Danish audience members commented “I never knew about that.”

out landmines with their bare hands. It is such a brilliant discussion of nationalism and how it’s possible to be “on the right side” but lose one’s humanity. It’s also possible to reclaim it. A number of Danish audience members commented “I never knew about that.”

Coming of age, identity, longing for identity—tackling the question of “who am I?” are themes that run through the stories we see told in the lights and shadows projected onto the cinema screen. This year with the festival taking place pre-and post inauguration of a controversial U.S. president the non-stop-news-cycle collided head-on with recurring themes that have run through all the years of the festival—namely immigration, nationality, ethnicity, oppression, justice, and sadly, injustice. We screened Renny Harlin’s (English language) film “Five Days of War” when the director was presented with a Cinema Without Borders award. The film tells the story of the five day Russian-Georgian War. After seeing the Crimean Peninsula taken over by Russia, and nerves in the Baltic countries on edge, it was impossible to not see a nexus with the Latvian documentary about life on the Eastern Ukraine/ Russian border that we screened.

We have consistently seen more stories about immigrants. The Nordic countries and Baltic neighbors have seen increased populations of immigrants into societies that were previously rather homogenous. The Baltic countries each had to absorb Russian populations when they were annexed into the Soviet Union. Those populations didn’t go away after the collapse of the Soviet Union. More untold stories for cinematic exposure… And both Europe and the United States are looking head-on into issues of increased xenophobia, and the realities of the refugee crisis.

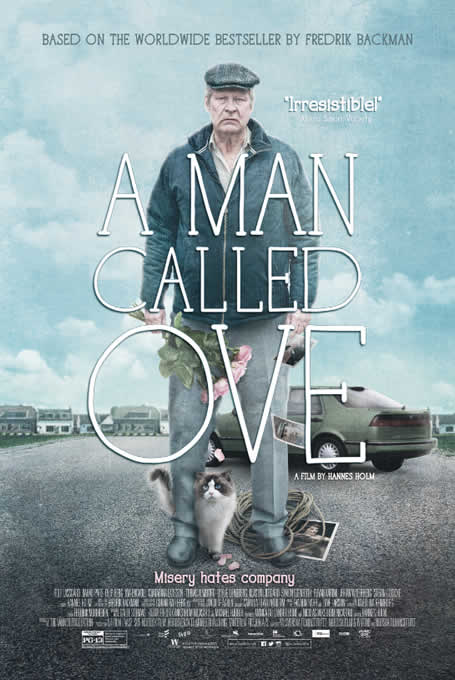

This year’s Swedish Oscar nominated film “A Man Called Ove” from Director Hannes Holm is a story of a relationship between a depressed widower who is a real curmudgeon and the new neighbors—immigrants from Iran. Naturally co-stars Rolf Lassgård and Bahar Pars would love to attend the Oscars with Director Hannes Holm. But again we find a collision with the news of a ban on people from certain countries entering the United States. It seems that Bahar Pars, although she has lived in Sweden for many years and is a citizen, also has an Iranian passport. That seems to be solved for the moment, but it is a reminder that stories on the screen of a theater or on the evening news are all about real people, real situations, real human suffering and need, with real consequences.

We’ve also had any number of “coming of age” stories. One of this year’s Icelandic film’s was HEARTSTONE—the story of an adolescent summer in a small village in which one “best friend” finds a first girlfriend and the other deals with the feelings he is developing for his best friend. The Finnish film “Little Wing” this year was a lovely “coming of age” story of a young girl.

In eighteen years we have seen a lot of talent grow and thrive and be recognized. A few years ago we had Norway’s “Kon Tiki” and Denmark’s “A Royal Affair” garner double Nordic “Best Foreign Language Film” nominations. And this year we have double nominations in that category with “Land of Mine” and “A Man Called Ove.” Both are excellent films and deserve the recognition—and who knows? “The Kings Choice” is also outstanding filmmaking. But I guess it would be greedy to think that we could have had three Nordic feature films receive nominations. Win or not, it doesn’t diminish the outstanding quality of the films.

In eighteen years we have seen a lot of talent grow and thrive and be recognized. A few years ago we had Norway’s “Kon Tiki” and Denmark’s “A Royal Affair” garner double Nordic “Best Foreign Language Film” nominations. And this year we have double nominations in that category with “Land of Mine” and “A Man Called Ove.” Both are excellent films and deserve the recognition—and who knows? “The Kings Choice” is also outstanding filmmaking. But I guess it would be greedy to think that we could have had three Nordic feature films receive nominations. Win or not, it doesn’t diminish the outstanding quality of the films.

Another thing I find interesting is the relationship between literature and film that we’ve seen. Many of the top films we’ve screened are based on popular novels from the various countries. “A Man Called Ove” was one such film based on the best selling novel by Fredrik Backman. The Swedish film “A Hundred Year Old Man Who Climbed Out the Window and Disappeared” was also based on the novel of the same name by Jonas Jonasson. The Finnish film “Purge” (set in Estonia) was based on the novel by Sofia Oksanen. Finnish actor, writer, director Peter Franzén has acted in over 40 films and has been a regular at SFFLA. His autobiographical novel “Above Dark Waters” marked his directorial debut for the movie version. As an actor we’ve seen him in roles as diverse as a racist skin-head who falls for a woman with a bi-racial son, to a brain-damaged soldier in Dog Nail Clipper, and a dashing young soldier in the war film “Ambush” that he starred in with his wife Irina Bjorklund.

From the beginning of the festival our goal was to create an annual opportunity for “cinema cultural exchange.” We can learn a lot about each other from the focus of our films. Stories of individuals tell us a lot about what’s on our collective minds. We focus on a different menu of films from a different part of the world—and engage in cinema cultural exchange and exposure to and exposure of a body of work that deserves more and more audience. We represent 8 countries and at least that many languages. America is a nation of immigrants; the film industry is a multi-cultural mix of talent from all over the globe. You or your ancestors may have thought they came here with nothing. But they all came with AT LEAST their stories— stories of ambition or escape, of love, of desire, of desire for a better life.

Despite many attempts in history—you can’t build a wall that will keep out ideas, images, and imagination—all in the service of the truth. I think somebody tried that once—it was called “the iron curtain.” But even that could not suppress the truth—or deny the need for people to tell their stories, to be seen, be heard. So here we are—after 18 years, sharing stories. And in that sharing we see that even with the unique identity of various countries and cultures, and languages, telling our stories reminds us of our common humanity.

I guess that’s why we’re already working on the 19th edition of SFFLA for next year. It’s always a matter of getting the funds and the films— (donations accepted at our web-site www.sffla.net). And then the fascination and fun begins.