The Cannes Film Festival forever fascinates with its flavor. The festival’s unwavering method that the French themselves are famous for, has held the festival flying high.

Every January, the festival announces the chairman of its international jury. Cate Blanchett, it will be this year, the Australian actress renowned for movies like Babel, The Curious Case of Benjamin Button, Elizabeth: The Golden Age and Blue Jasmine, which fetched her an Oscar for best actress.

And of course, three weeks before the festival starts, the titles are announced at a Paris press conference. This year, Cannes’ 71st edition begins on May 8, but with the Berlin Film Festival just over, the air is thick with the basket of probables that will roll into the Riviera.

As one French journal quipped: “As always, theories have started swirling around the probable selection that will be unveiled in April by Cannes’ General Delegate Thierry Frémaux, but we can already say that on paper, the 2018 edition looks to be utterly breathtaking, making the hunt for this year’s Palme d’Or (festival’s top prize) all the more exciting.”

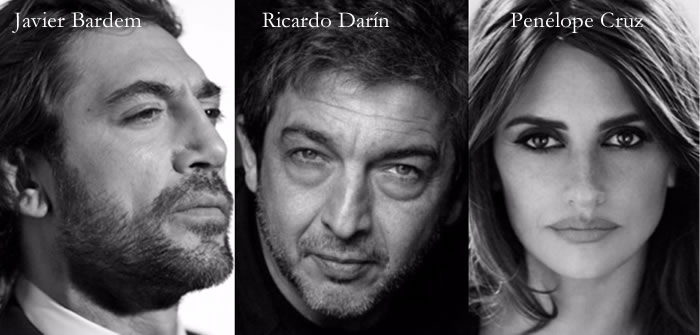

Some of the titles that just about every critic and anybody else who will be at Cannes this May will look forward to are: The Wild Pear Tree by Turkey’s Nuri Bilge Ceylan, Loro by Italy’s Paolo Sorrentino, Peterloo by British director Mike Leigh, Everybody Knows by Iran’s Asghar Farhadi, The Death and Life of John F Donovan by Canada’s Xavier Dolan, Ash Is Purest White by China’s Jia Zhangke, Sunset by Hungary’s László Nemes, The Favourite by Greece’s Yorgos Lanthimos, Donbass by Ukraine’s Sergei Loznitsa, Where Life Is Born by Mexico’s Carlos Reygadas, The Sisters Brothers by France’s Jacques Audiard, Vision by Japan’s Naomi Kawase and Shoplifters by fellow Japanese, Hirokazu Kore-eda.

Also, there can be Roma by Mexico’s Alfonso Cuaron, Steve McQueen’s Windows from the UK, The Image Book from Jean-Luc Godard and Terrence Mallick’s American drama, Radegund.

It is clear from the list that Cannes is a lot about permanence and loyalty. So many of the helmers have had a relationship with the festival – often for long years. Some of the striking examples are Kawase, Dolan, Leigh, Cuaron, Malik and Farhadi.

Such continuity has been one of the strongest pillars of Cannes – which has been quite unlike that at Venice or Berlin. Both Venice – which happens every autumn on the quaint little island of Lido, off the mainland, Berlin do go in for changes, both cosmetic and otherwise. Last year, Venice opened a swanky courtyard, and its experimentation has ranged from such structural changes to directors.

One can, therefore, safely conclude that Cannes stands for continuity. It follows then that the festival is less likely to take a new director from India, and this can be a reason for the country’s absence on the Riviera. At least, most of the times.

Paradoxically, while Indian representation outside of movies at Cannes has grown phenomenally in the past decade, the cinema from a nation which produces close to 2000 films a year (making it the largest in the world) is often not to be seen at the May festival. There are no clear answers for this, but I would suppose that a lot more PR push is needed for an Indian title to roll its way through hundreds of offerings if it has to catch the eye of Cannes selectors.

Source: Hindustan Times