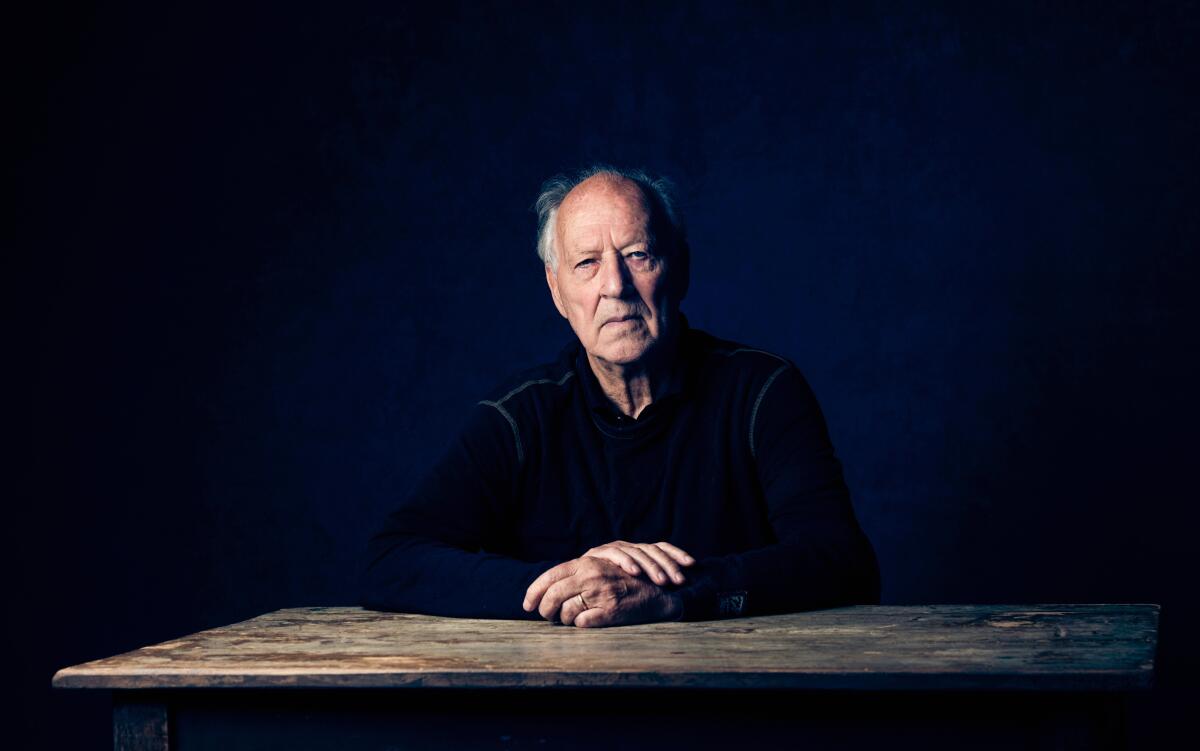

The German magazine Der Spiegel interviewed Werner Herzog, the German filmmaker who, at 83, has lived for decades in the United States, primarily in Los Angeles. Herzog has directed more than 70 feature films and documentaries, and his working methods and fiercely idiosyncratic storytelling have consistently blurred the boundaries between genres. He has never shied away from confronting the world directly. In his filmmaking workshops, he famously urges participants: “Go work as a bouncer in a sex club. Work as an orderly in a mental institution. Go to a dairy farm and learn how to milk cows.”

His most recent film is the documentary The Ghost Elephants, shot in Namibia and Angola. In August, at the Venice Film Festival, Herzog was awarded the festival’s honorary Golden Lion for lifetime achievement. The film is scheduled to stream in March on Disney+. One of Herzog’s newest books, published in 2024, is titled The Future of Truth.

Der Spiegel: Mr. Herzog, in December in Munich you presented a film prize named after you to a young British director. Do you have hope for the next generation?

Herzog: I am often seen as a prophet of a dark future, but that is completely untrue. I see extraordinarily talented young people, and I look forward to what is still to come. In the end, it is irrelevant to me whether I will still be around to witness it.

Der Spiegel: Are you equally optimistic about the future of the world?

Herzog: I do not like placing myself in categories such as optimist or pessimist. As a species, we probably will not endure on this planet for a very long time. That seems quite evident. But it does not make me anxious.

Der Spiegel: Why do you think humanity will not last long?

Herzog: Biologically, we are relatively fragile—far weaker than many other mammals, even weaker than reptiles, beetles, or microbes around us. That is one aspect. The other is that we have made the ice on which we are walking very, very thin. I mean our collective behavior.

Der Spiegel: In what sense?

Herzog: If the internet were to fail for an extended period, things would deteriorate rapidly. Financial transactions would halt; water, fuel, and food supplies would collapse. We saw something similar when Hurricane Sandy hit New York in 2012. My wife was there at the time. In southern Manhattan, power suddenly went out, elevators stopped, people had to climb 54 floors in the dark. Toilets would not flush. The problem is that as a society we have made ourselves dependent on technology. Others may worry about that. Personally, technological innovation mainly arouses my curiosity.

Der Spiegel: You have recently opened an Instagram account. Sometimes you are grilling steak; other times you appear with a mariachi band.

Herzog: The posts you mention are lighter in tone. But unlike the usual trivialities online, I only post things that carry meaning and narrative substance—things that spark curiosity. One of my sons persuaded me. I do not even own a smartphone. He somehow uploads these things. How? I do not know. I do not advertise anything there. I simply give access to things that have substance and that relate to subjects occupying my mind. I do not even follow the reactions.

Der Spiegel: The reactions are entirely positive; three-quarters of a million people follow you.

Herzog: That is because my films have reached entirely new audiences through the internet. A film I made in the mid-1970s is suddenly being watched by 15-year-olds in Montana or somewhere in Brazil. Fan clubs form and send me emails—almost all of them young—immediately wanting to know what happened in 1976 during the making of Heart of Glass, how I hypnotized the actors and directed them.

Der Spiegel: That film is about a legendary early nineteenth-century Bavarian seer. Why are people in the remotest corners of the world watching such films today?

Herzog: Because I am a good storyteller. Language, narration, and poetry are cultural achievements acquired over tens of thousands of years. What dominates mainstream cinema today is largely fueled by loud explosions, digital effects, and star power. As a result, the great storyteller has grown impoverished. That absence is felt worldwide. I think that is why attention suddenly turns to my films and books—because word spreads: there is a story here.

Der Spiegel: You have lived in the United States for many years. Is the “year of horror,” as many in Germany describe it, your perspective too? “The existential trait of the middle class is anxiety; without anxiety it cannot exist.”

Herzog: Absolutely not. That is the narrative of the German media, and Der Spiegel is no exception. Your image depends on an audience that largely belongs to the middle class. The existential trait of the middle class is anxiety; without anxiety it cannot exist. The media play a major role in weaving that narrative. That is why I trust you only to a certain extent. On important matters, I look at what China’s news agency says, what Al Jazeera says, what the Vatican says. That is how I try to form a more multilayered picture of political reality.

Der Spiegel: Even from China, where perspectives are clearly shaped by propaganda?

Herzog: Even so, it can be enlightening. I am not a fool who cannot recognize propaganda.

Der Spiegel: What do German media misunderstand about the United States?

Herzog: They are still surprised by what happens in American politics. I am not. I have long known the heartland—the central states. I have heard friends on the coasts say in political debates, “We must find a way to neutralize the votes of the flyover states,” meaning the states Californians and New Yorkers merely fly over. I find that cynical and wrong.

Der Spiegel: Donald Trump himself is a wealthy New Yorker, hardly a representative of the heartland.

Herzog: That is irrelevant. He promised to smash the system. That, rather than mere campaign rhetoric, is the basis of his success. It must be taken seriously.

Der Spiegel: Is the public anger justified?

Herzog: Partly exaggerated, partly entirely understandable. I have worked in Pittsburgh, New Orleans, Wisconsin, and Texas. People there are underrepresented, underpaid, marginalized, with limited access to higher education. I want to tell my friends in Los Angeles: you must show these people they matter and that you do not despise them. I see parallels in Germany with the party Alternative for Germany.

Der Spiegel: In what way?

Herzog: I think the idea of eliminating such movements through a party ban is wrong. Political ideas cannot be regulated by prohibition—it is impossible. It would signal weakness in parties, parliament, and the judiciary. Roll up your sleeves and respond politically.

Der Spiegel: As a filmmaker, you have also engaged with artificial intelligence. In the documentary About a Hero, an AI system trained on your films “hallucinated” a screenplay. Is fear of machines exaggerated?

Herzog: We need not fear, but we must remain vigilant. Warfare will change; so will our relationship to the real world. We must ask: how far do we want to entrust our thinking and dreaming to AI?

Der Spiegel: Can AI dream?

Herzog: In some sense, it already can. Dream sequences—from script to imagery, sound to dialogue—can now be entirely generated by AI. But they are stillborn. They can be exposed instantly: their surface is perfectly smooth, accompanied by a whispering tone of optimism and positivity. For the next 2,000 years, AI will not make a film half as good as one of mine.

Der Spiegel: Because it cannot tell good stories?

Herzog: Exactly. It can only imitate, drawing from millions of stories told on the internet. But the internet operates on the lowest common denominator—whatever generates clicks. In the end, you get mainstream, purely commercial cinema. You can smell the barn from miles away.

Der Spiegel: Yet there are real consequences. This year, workers in the film industry repeatedly complained about losing jobs due to AI.

Herzog: Oh God! A woman from the German Federal Association of Film Directors wrote to me about this. I despise a culture of lamentation. My message is: “For heaven’s sake, make films AI could never make! Roll up your sleeves and create good films! I am launching a counterattack myself!”

Der Spiegel: How?

Herzog: AI can now imitate my voice—more convincingly than actors can. So I counter it. Recently, I was asked to record an introduction for a video game. There, I try to behave and speak like an AI character. If AI imitates me, I will imitate AI.

Der Spiegel: Your distinctive voice and strong accent have led to appearances in major American productions—you have appeared on The Simpsons and in The Mandalorian from the Star Wars universe. Is that fun for you?

Herzog: It is work. Some actors prepare intensely and immerse themselves in roles. I do not need that; I am built more simply. In the action film Jack Reacher, for example, I only had to generate menace. They wanted me because I can do that calmly and penetratingly. And yes, I earned my fee. The voice is secondary. I radiate menace even in Japanese or Portuguese dubbing.

Der Spiegel: Are you ever surprised at where your acting fame has taken you?

Herzog: No. Because I know these appearances are only the smallest part of what I do. This year alone I made two films and published two books. And I believe what I write will outlive the rest.

Der Spiegel: Why?

Herzog: Books are condensed; they convey substance directly. In cinema, there is always the camera and the technology, actors with their peculiar psychologies, financial problems, post-production—dozens of layers before you reach the final image on screen. Literature is immediate, almost like the way I am speaking to you now.

Der Spiegel: In your latest book, The Future of Truth, you warn young directors that without reading they will never make a great film.

Herzog: Exactly. I hardly watch films; I read. That is how I enter other intellectual worlds. In my house there is barely space for books—many crooked walls—but still there are always 100 to 150 volumes. Hölderlin, Robert Walser, of course Büchner and Kleist. If I wake at three in the morning, I must be able to reach for them at once. “The world reveals itself to those who walk on foot. That is how we come to understand it.”

The conversation continues…