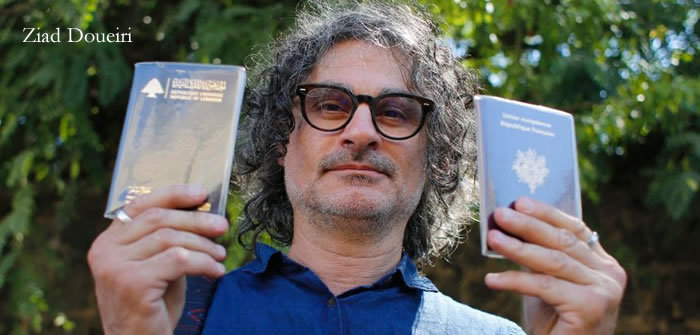

Lebanese film director Ziad Doueiri made headlines recently when authorities in Beirut arrested him at the Beirut-Rafic Hariri International Airport for questioning about his links to Israel.

He was almost put on trial on charges of “normalizing relations” with Israel because of his visit here in 2012 as part of the filming of his previous movie, “The Attack.” But he managed to prove his “innocence.” Doueiri entered Israel on a U.S. passport, which he holds along with his French and Lebanese passports. Nonetheless, he was also detained and questioned in Israel.

But the bigger commotion is over his new film, “The Insult,” released in 2017. It reawakened memories of the 15-year Lebanese Civil War. It is the only Arab film included in the shortlist for the Oscars this year in the category of Best Foreign Language Film, and is expected to compete against the Israeli film “Foxtrot” – if both films are among the five finalists to be announced in January, with the awards ceremony being held on March 4.

“The Insult” starts with the story of a scuffle between two Lebanese citizens. One, Yasser, is a Palestinian refugee, the other, Tony, is a Lebanese Christian. Tony owns a car repair garage while Yasser is an engineer who is sent to check building violations on the street where Tony’s garage stands.

While he is passing by Tony’s home, water drips onto Yasser’s clothes as Tony waters the plants on his balcony. The argument between them develops into swearing and insults and then Tony yells at Yasser that it’s a shame Ariel Sharon didn’t wipe them out, a curse that was common well over 30 years ago – and still is today.

From here the story moves on into the courtroom and when the two lawyers – one a Christian representing Tony, and his daughter, who is representing Yasser – expand the legal case from a personal dispute into a national issue, and then all the feelings of disappointment and hostility locked up in the hearts of the Lebanese since the end of the Civil War, which no one dares bring up in public out of fear they will set off an enormous flood, stream out.

The film met with great enthusiasm and won prizes at Arab film festivals, but the West Bank city of Ramallah refused to allow the film to be shown there – but not because of its content. Ramallah and the Days of Cinema Festival gave in to the BDS movement, which claimed Doueiri normalized relations with Israel, and in his previous film even hired Israeli actors, so he must be boycotted “eternally.”

Kamel El Basha, the actor who plays Yasser, called the decision to boycott the film “disgraceful,” and bitterly made fun of them: “I take off my hat to the impassioned group of young people who succeeded in ‘beating’ the mayor of Ramallah and forcing him to adopt their demands, even though they don’t represent more than a ten-thousandth of the Palestinian people.”

Very few movies have been made in Lebanon about the Civil War, in the same way many Lebanese writers have avoided dealing with the explosive subject. But Doueiri is not just a courageous and exceptional director in how he works; he has brought to this film his harsh experiences of someone who lived in the western quarter of Beirut, a neighborhood with a Muslim majority.

In an emotional interview with the BBC in September, Doueiri describes his life in the Muslim part of the city split by the civil war, and especially the abyss separating Christians and Muslims. Doueiri said that sometimes he could cross the line between West Beirut and East Beirut because of his connections with a friend in the Christian Phalangists, Doueiri told the interviewer, Giselle Khoury (widow of the prominent Lebanese journalist Samir Kassir, who was murdered in 2005 in a wave of assassinations most likely instigated by the Syrian regime against its enemies).

Suddenly, the interview turns personal when Khoury and Doueiri share the same experiences from the opposite sides of the barricades. Doueiri told her he was amazed to see what was happening in the Christian area where she lived. It was clean, there were restaurants and bars – compared to the garbage that filled the streets in the Western part where he lived. In his part of the city there was an endless number of political parties; in the Christian area it looked as if everyone came together for a common goal.

The division between “us,” the Muslims, and “you,” the Christians, is not just an ethnic or geographic matter, but is part of a much more important theme in the movie. The “Christians” are Sabra and Shatila, the Phalangists, the murderers and collaborators with Israel. The “Muslims” are the victims, especially when they are Palestinians, such as Yasser the engineer sent to check for building violations and is the target of all the curses.

Doueiri speaks quickly, breathlessly, as if being pursued by a time machine that is about to crash and break up into pieces. He needs to finish telling the entire history of Beirut before the interview ends, he fires off the names of friends from the war period, some have moved into politics, others were killed in battle or assassinated, while he moved to the United States to study – a distance that will help him examine the bloody events in Lebanon from a different perspective, one he seems able to separate from his ethnic and religious background.

But such a separation can no longer really exist in Lebanon. It is enough just to watch the legal battle of Yasser’s lawyer against her own father, Tony ‘s lawyer, to remember the shocking descriptions by Lebanese author Hoda Barakat in her book, “The Stone of Laughter,” which has been translated into Hebrew. Barakat shows the rending of entire families between supporters of the Phalangists and their opponents, between children and parents, between residents of one alleyway and those of its neighbor.

The movie was included i`n the list of the 10 most controversial films of 2017 put together by the Lebanese website Raseef22 as part of its end of the year rundown of Arab literature and cinema. Now all we can do is hope that someone will take on the mission of bringing “The Insult” to Israeli theaters too.

Written by: Zvi Bar’el for Haaretz