Naser Malek Motii, the superstar of Iranian cinema for almost three decades, passed away after a long illness in the hospital in Tehran, Iran, on May 25, 2018. He was 88 years old.

He had a low voice and was reserved with his words. He was courteous and bashful, and you could read the kindness, humility and humanity in his face.

He was a decent, humble, selfless man. A gentleman, without any hypocrisy, and with a manner of true sportsmanship. He was a man who always helped others, in and out of the film industry, and did his best to build and improve Iranian cinema since 1949.

He was a decent, humble, selfless man. A gentleman, without any hypocrisy, and with a manner of true sportsmanship. He was a man who always helped others, in and out of the film industry, and did his best to build and improve Iranian cinema since 1949.

Malek Motii was the son of a cinema owner. He became a sports instructor at a primary school in Tehran, until, in 1949, he was given an opportunity to appear in a minor role in a comedy film called Spring Variation by Parviz Khatibi, a pioneer writer/director.

Ironically, Khatibi cast another friend, Ezzattollah Entezami in another minor role in the same film, ironic because both actors would go on to become super famous in Iranian cinema. Nasser Malek Motii’s magnetic looks, considerable height and good physique turned out to be key to his appearance in his third film, 1952’s Velgard (Vagabond) by Mehdi Raisfiruz, a performance that made him a superstar overnight, after which he remained the king of Iranian cinema for three decades, until the revolution in 1979, whereas Entezami traveled another route to success, working largely in theatre until 1968, when his appearance in Daryush Mehrjui’s The Cow made his name known internationally.

Velgard (Vagabond, 1952)

Mohsen Badi’, educated in France and England was a sound engineer and an innovative who thought himself cinematography, editing, printing and had established a film laboratory. He was a sound recorder of Zendaniye Amir (The Prince’s Prisoner) directed by Esmail Kushan in 1948. Badi’ invented an opticcal sound machine to record the sound on the edge of the negative and it was a success. Then he produced and shot his first film Shekare Khanegi (Domestic Affairs) in 16 mm in 1951.

Mohsen Badi’, educated in France and England was a sound engineer and an innovative who thought himself cinematography, editing, printing and had established a film laboratory. He was a sound recorder of Zendaniye Amir (The Prince’s Prisoner) directed by Esmail Kushan in 1948. Badi’ invented an opticcal sound machine to record the sound on the edge of the negative and it was a success. Then he produced and shot his first film Shekare Khanegi (Domestic Affairs) in 16 mm in 1951.

Mohsen Badi’ had just established the Iran Film Studio with two partners, and they were looking for their first production, when Mehdi Raisfiruz, a graduate of the vocational acting school in Tehran, landed there to create his first film. He described to the producers the story that he wanted to tell, as he had not put it down on paper yet. Badi’ liked it, so he wrote it overnight and production started immediately. The producers wanted to hire Mohamad Ali Daryabeigi, who had studied acting and directing for theater in Germany, and had already directed two films: Tufane Zandegi (The Tempest of Life, 1948) and Shekare Khanegi (Domestic Affair, 1951), as director, but Raisfiruz convinced them that he was suited to direct his own story, filming two exemplary scenes that pleased them quite a bit and caused them to approve his hiring as director. Everyone got involved in casting the picture. Raisfiruz wanted a new face for the leading role and, after looking at a lot of photos, chose Naser Malek Motii, who had previously acted in small roles in two films: Varietehye Bahari (Spring Variation, 1949) and Shekare Khanegi (Domestic Affairs, 1951). The actress Sudabeh was brought in by one of the producers to play the character of the wife and Homa Sarshar was chosen to play the kid daughter. (Sarshar would later become a distinguished journalist and writer.)

The production began in May and took almost six months to finish. Mohsen Badi’ did a good job as cinematographer and editor. The film was shot on location and inside the studio during Dr. Mohammad Mosaddeq’s time as prime minister; for a short period, owing to a military-induced curfew, they could not shoot outside after midnight.

The story line was about a man named Naser, who lives happily with his wife and her daughter, until he develops a gambling problem, loses all of his money, and is forced to leave his family and go live in a small city. After 18 years, he returns to find them, but discovers that he is too late.

The story line was about a man named Naser, who lives happily with his wife and her daughter, until he develops a gambling problem, loses all of his money, and is forced to leave his family and go live in a small city. After 18 years, he returns to find them, but discovers that he is too late.

Velgard was released into two cinemas, the Homa and the Diana, on 26 Azar, 1331 (December 17, 1952), and instantly became a hit, running for more than three months. The production budget was 900,000 rials (at that time, one dollar was worth 90 rials, making the budget almost ten thousand dollars). Considering that the average movie ticket price was ten rials, Velgard’s total box office broke the record, earning about four hundred million rials in Tehran and half a million rials (equal to 55,000 dollars) in the entire country. It made twice that of the previous record-holder, Sharmsar (Ashamed), which earned about 2,200,000 during 108 days onscreen the previous year. Velgard’s success was simply unprecedented.

Velgard was the 20th feature film to be produced in Iran, and represented a very different type of film than those that had been released before it. Both the social theme (a gambling addiction destroying a family) and his improved, more polished and more artistic techniques and camerawork set it apart. The black and white film was also shot with a 35 mm negative, whereas most other films were shot in 16mm.

Velgard was an excellent vehicle for Naser Malek Motii to display his acting talent, and he became an instant star. Raisfiruz, the director, told me: “After the film had been in release for a week or two, Malek Motii went to the cinema to watch the film and get a sense of its impact. After the film finished, he left the theater to find a taxi. The crowd outside was very large and it wasn’t long before the people recognized him. He had just gotten into his taxi when the crowd rushed it, grabbing onto the vehicle, holding it and raising it up while the engine was running, so that its tires were spinning in the air. You could not believe how popular he had become!”

Velgard was also more favorably received by the critics, making it a turning point in Iranian cinema both artistically and commercially. The downside of its success (as so often happens in the movie business, Hollywood itself being a premiere example of this) was that it caused other producers immediately to try to copy its melodramatic story line over and over again, in films such as Gerdab (Vortex, 1953), Iran’s first color film, and Gheflat (Negligence, 1954), also starred Malek Motii and some of which featured other leading actors.

Velgard was also more favorably received by the critics, making it a turning point in Iranian cinema both artistically and commercially. The downside of its success (as so often happens in the movie business, Hollywood itself being a premiere example of this) was that it caused other producers immediately to try to copy its melodramatic story line over and over again, in films such as Gerdab (Vortex, 1953), Iran’s first color film, and Gheflat (Negligence, 1954), also starred Malek Motii and some of which featured other leading actors.

Despite this, Velgard stood out as the better, more unique film, being named by many critics as the best Iranian film of that time. Parviz Davai, who was a very famous critic in the ‘40s and ‘50s, said in an interview (Setareh Cinema, #63, May 13, 1956): “For the first time, after I watched Velgard, I became hopeful about the future of Iranian cinema.” Cinema and Theatre magazine wrote, on January 27, 1953: “Velgard is the best Iranian film to have been produced up until now.” Toghrol Afshar, another film critic, wrote: “…Velgard is as far away from trite as it could be, and it promises a better future for Iranian cinematography and Iranian cinema in general” (Jahane Cinema, # 10, January 4, 1953).

Velgard also featured a number of special effects (trucage) successfully executed by Badi’ that attracted the eye of Tro Al-Gilani, a film critic who had just published a book called Technique of Cinema in 1952.

In his review in Cinema & Theatre magazine (#4, December 31, 1952) titled “How the Special Effects in Velgard Were Created,” Al-Gilani wrote, “In Velgard, there are three examples of truncate that are very well done:

- When Susan comes to the porch and sits on the easy chair, and, after few seconds, her soul flies into the sky.

- In a continuation of the first effect, Susan is seen ascending, and a dark blue sky full of stars appears behind her.

- The scene that shows the four stages of Naser’s life.

I have to confess that all of these special effects are done very carefully and very well, and the fact that this kind of thing could be pulled off in an Iranian studio makes us hopeful that this cinematographic Technic will improve very fast in our dear country.”

Velvet Hat

After Dlekash, the Iranian singer/actress, wore a velvet hat (in Zalem Bala (Heartbreaker, 1957)), the following year, Majid Mohseni, a very talented actor/director, created a character with a very particular look that came to be known as ‘Jahel,’ in his modernist film Late Javanmard (The Chivalrous Hooligan). Jahel became one of the most important characters in Iranian cinema, particularly after Naser Malek Motii played the lead in Kolah Makhmali (The Velvet Hat, 1962), and put his own stamp on the Jahel character. A Jahel character is usually an illiterate man who makes his way in life by acting like a tough guy. The Jahel character can be categorized into two different iterations that have been used over time: “Luti” and “Na-Luti.” The former refers to a group of men who all have the common qualities of manhood, such as bravery, honesty and frankness, while the latter lacks all of these.

After Dlekash, the Iranian singer/actress, wore a velvet hat (in Zalem Bala (Heartbreaker, 1957)), the following year, Majid Mohseni, a very talented actor/director, created a character with a very particular look that came to be known as ‘Jahel,’ in his modernist film Late Javanmard (The Chivalrous Hooligan). Jahel became one of the most important characters in Iranian cinema, particularly after Naser Malek Motii played the lead in Kolah Makhmali (The Velvet Hat, 1962), and put his own stamp on the Jahel character. A Jahel character is usually an illiterate man who makes his way in life by acting like a tough guy. The Jahel character can be categorized into two different iterations that have been used over time: “Luti” and “Na-Luti.” The former refers to a group of men who all have the common qualities of manhood, such as bravery, honesty and frankness, while the latter lacks all of these.

Malek Motii acted in almost one hundred feature films of the more than 1200 made during the Pahlavi regime, before the revolution of 1979, almost 9 percent of the total output, and his name was a guarantee of a return on capital. His strong popularity among all levels/classes of society and his place in popular culture made him the most beloved actor in Iran. He was the industry’s sole superstar until the mid-1960s, when Mohammad Ali Fardin in Ganje Qarun (The Treasure of Qarun-1965) achieved a similar level of popularity, after which Behrouz Vossoghi took the top spot with his very popular performance in Qeysar (1969). All three of these superstars and other veterans of the golden age of Iranian cinema, among them leading actresses, including Iren, Forouzan, and Pouri Banai, and even those who only played supporting roles, were banned from acting after the Islamic revolution came to power.

Malek Motii’s major films are: Afsungar (Enchanter, 1952), Gerdab (Vortex, 1953), Iran’s first color film; Gheflat (Negligence, 1954); 4 Rahe Havades (The Crossroad of Events, 1955); 17 Ruz beh E’dam (17 Days to Execution, 1956); Sowdagarne Marg (Death Traders, 1962); Qeysar (1968); Towqi (Pigeon, 1970); Raqqasehye Shahr (City Dancer, 1971); Seh Qap (3 Knucklebones), Pol (The Bridge, 1971); Khaterkhah (Amorous, 1972); Qalandar (The Wandering Dervish, 1972), Ten Little Indians (1974); Bot (Idol, 1976); and Soltan Sahebqaran, a TV series that aired in 1974.

Malek Motii’s major films are: Afsungar (Enchanter, 1952), Gerdab (Vortex, 1953), Iran’s first color film; Gheflat (Negligence, 1954); 4 Rahe Havades (The Crossroad of Events, 1955); 17 Ruz beh E’dam (17 Days to Execution, 1956); Sowdagarne Marg (Death Traders, 1962); Qeysar (1968); Towqi (Pigeon, 1970); Raqqasehye Shahr (City Dancer, 1971); Seh Qap (3 Knucklebones), Pol (The Bridge, 1971); Khaterkhah (Amorous, 1972); Qalandar (The Wandering Dervish, 1972), Ten Little Indians (1974); Bot (Idol, 1976); and Soltan Sahebqaran, a TV series that aired in 1974.

He directed nine films, including his debut, Death Traders, a solid crime drama. He also spent some time working in theatre, and his powerful performance in Jean Paul Sartre’s Dirty Hands with Fakhri Khorvash is still well remembered today.

Malek Motii, during his three-decade career, acted in more than one hundred films, working with both the best and the worst directors. He learned from those who were educated and talented and transferred his experience to those who were not good at directing.

He had a good relationship with the camera, which, regardless of who was behind it, loved his face, as did the audiences who rushed to the theaters to see him without caring about the value of the film. He never left Iran, and remained there throughout his life, for love of his homeland and the people who loved him.

Malek Motii was a symbol of what went wrong with Iranian cinema in regard to all of those who were forbidden to perform. Although he and a few others were able to survive commercially, the rest were left without jobs or any financial support, making it a tremendous struggle simply to survive without work or any kind of insurance. A few committed suicides, some died in obscurity.

After the revolution, he acted in only one film, called Barzakhiha (The Imperiled, 1982), after which the government imposed a media ban on before revolution celebrities.

Malek Motii earned the Best Actor award at both the third (1971) and fourth (1972) Sepas (National Iranian Film Festival), the first for his role in Raqqasehye Shahr and the second for Seh Qap.

His impact and presence in three decades of Iranian cinema were undeniable. Malek Motii and the other stars, both men and women, not only helped to establish the film industry in Iran, but also brought its annual production from just a few films to almost 80, resulting in an industry that employed almost ten thousand people.

After the arrival of Islamic values in 1979, with few exceptions, all film stars, both male and female, including Naser Malek Motii, Fardin, Behrouz Vossoughi, Iren, Forouzan, and Pouri Banai, Katayoun, and many more were banned from performing, and strict restrictions were placed on the movie industry by the government. (In fact, all of the arts in Iran were affected, including the music industry, with pop stars and even classical/traditional singers being banned as well.)

Malek Motii was forced into seclusion for many painful and heartbreaking years. He opened a confectionary and later became an estate agent. The new situation in his life never made him bitter and he never begged to be allowed to return to acting. He was not a man to offer false praise or flattery to anybody for the purpose of his own advancement, a stance that he maintained all the way up to his death.

Malek Motii lived under the media and acting ban for almost forty years, lasting until the news of his death was announced by state television. The lack of any scandal in his life, his economic impact on the film industry and his popular status made him an icon of the national heritage of Iran and Iranians.Ira

Malek Motii lived under the media and acting ban for almost forty years, lasting until the news of his death was announced by state television. The lack of any scandal in his life, his economic impact on the film industry and his popular status made him an icon of the national heritage of Iran and Iranians.Ira

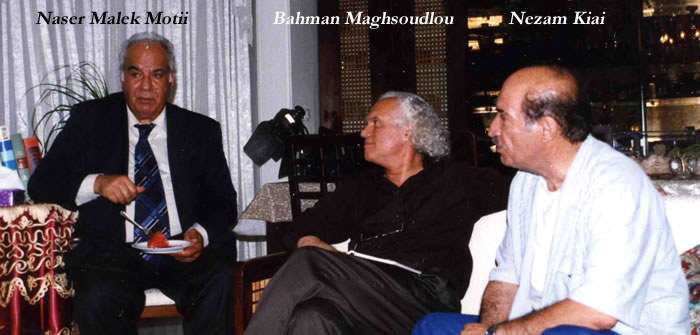

In 2002, I interviewed him for over four hours at his home, which included shooting footage of him wearing his famous velvet hat. This was part of a feature documentary on the actor that I hope to be able to finish by next year, so as to bring his side of story to the silver screen and the historical record.

New York, November 14, 2018