Painter, writer, film director, Philippe Mora has forged an idiosyncratic path. His Mad Dog Morgan (1976), starring Dennis Hopper, is now considered a classic of Australian cinema. Mora subsequently directed, among other films; The Return of Captain Invincible (1983), A Breed Apart (1984), Howling II… Your Sister is a Werewolf (1985), Death of a Soldier (1986), Howling III: The Marsupials (1987), and Communion (1989). Over his long career, he has worked with actors Frank Thring, David Gulpilil, Jack Thompson, Alan Arkin, Christopher Lee, Rutger Hauer, Kathleen Turner, Christopher Walken and James Coburn.

We spoke with the ebullient Mora from his home in L.A.

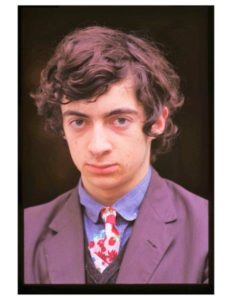

Steve Cox: You were born in 1949, and you have described your childhood as ‘culturally privileged’. Your parents were iconic artist Mirka Mora and much respected restaurateur and gallerist, Georges Mora. You grew up among the raffish, bohemian demi-monde in Melbourne. What are your thoughts when you look back on such a golden upbringing?

Philippe Mora: It’s golden now, but then it was only golden on certain occasions – really, like most childhoods, it was up and down. I did learn how to draw and paint, and, along with Passiona and Blue Heaven milkshakes, I tried wine from flagons left over at adult parties. I did witness adults having freak-outs in this bohemian world, which was always entertaining to us kids. We were told never to mention Sidney Nolan (who we didn’t know anyway) around Sunday Reed. One day, at Heide, some hapless guest mentioned him, and she took off, wailing like a Banshee, to our great amusement – then, after a few moments, we went back to watching Disneyland.

Kids can be heartless – which Albert Tucker brilliantly illustrated in Redmond Phillips’ (writing as a fictional child, Julian Prang) book Playing with Girls (Melbourne, Reed & Harris – publishers of the avant-garde Angry Penguins magazine – 1945). Tucker lived upstairs from us at 9 Collins Street, Melbourne. One day I broke in, with my younger brother William, and we looked around. In a drawer, we found photos of nude women with big breasts. Harmless softcore by today’s standards. I wrote across one: ‘Bert, I never want to see you again, we are over!’ or something like that, signed ‘Helen’. I was absolutely convinced he would never know it was the Mora kids responsible because I prided myself on adult handwriting. He went berserk, called the cops and they gave us a stiff talking to, keeping a straight face almost to the end. The policeman said: ‘Just so you know, son, the giveaway was ‘HELEN’. He does not know a ‘HELEN’ who looks like that.’ My parents also admonished us, but they asked me to describe the photos.

Many years later, I had some incredible discussions with Tucker, who was a UFO buff. He showed me 8MM films of himself, supposedly being ‘healed’ in the Philippines, with gory shots of nameless goo being removed from his chest. Notwithstanding some eccentric ideas, he was a brilliant, informed, erudite iconoclast.

I do recall some extraordinary scenes, such as artists – now all major Australian cultural figures – putting themselves ‘on trial’ for their work. One artist would be the accused, another the judge, others the prosecutor and defense lawyers. I’m talking about a cast like John Perceval, Charles Blackman (a great actor), David Boyd, Laurence Hope, Barry Humphries, Ian Sime, Georges Mora, Neil Douglas. Perceval and David Boyd, in particular, would entertain us with their medieval gas, like in Breughel’s paintings – David would light his farts and John would blow alcohol onto fire in a fire-eating display. Sometimes, the adults would cook a whole sheep, which was always spectacular.

Rarely could anyone sell a painting and my parents fed a lot of artists – which is one of the reasons they started the Mirka Cafe. Arthur Boyd’s painting, ‘Melbourne Burning’, was over our bed at 9 Collins Street for years, and that apocalyptic masterpiece is still in my mind today. Years later, Arthur would give me some cash to help make my first 35mm film Trouble in Molopolis (1969).

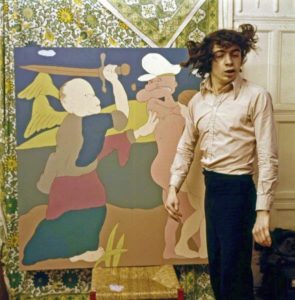

SC: I first became aware of your work when I was 15 – many years before I met you. I had saved up to purchase Alan Aldridge’s The Beatles’ Illustrated Lyrics, which featured work by international artists, illustrators and photographers. (For example, David Hockney’s drawing of a comfortable-looking bed accompanied the song ‘I’m So Tired’). I was really fascinated by your contributions, which illustrated the songs ‘I Am the Walrus’ and ‘Good Morning, Good Morning’. The rather grotesque figures ranged across flattened backgrounds were fresh and exciting, and I must admit that these and other paintings of yours, which I managed to hunt down at the time, were an influence on some of my own paintings during my first year at the Victorian College of the Arts, in 1978.

PM: My numerous shows at Clytie Jessop’s gallery (London) were all a great success, getting much attention. Even film director Michelangelo Antonioni acquired one – a take on Degas’ Absinthe drinker, called ‘The Cannabis Smoker’. Eric Clapton bought some. Mick Jagger bought an image of a man playing a harmonica. Francis Bacon was transfixed by an image of a naked old woman, based on a work by Dürer. I was eclectic in my influences and I loved comic books, particularly Crazy Kat and Classics Illustrated. Some art heavyweights really liked my paintings. The godfather of British Pop Art, Eduardo Paolozzi, was particularly fascinated, and R.C Kennedy of Art International gave me some rave reviews (and admonishments to slow down!). Joseph Beuys and Klaus Staeck liked my paintings at Sigi Kraus Gallery. I got tired of seeing my colour paintings reproduced in black and white in newspapers and magazines. So, I figured that if I painted a show in black and white and grey, when the images were reproduced, they would be in their correct ‘colours’, right?

SC: Well, it worked for Picasso’s Guernica!

PM: Exactly! So, that’s what happened – and Art International reproduced my painting, ‘Experiment on a Rat’. Staeck liked it so much that he commissioned me to do a screen print of it for his printing house in Heidelberg.

SC: So, this was in the 1960s, when you had relocated to Swinging London, joining many other Australian artists, intellectuals and rock bands who had made this pilgrimage, such as Brett Whiteley, Martin Sharp, Germaine Greer, Barry Humphries, Clive James, The Bee Gees, The Easybeats, et al. Your experience there reads like a who’s who of the cultural elite. You contributed to the ground-breaking, underground OZ magazine. You shared digs with Eric Clapton. You staged exhibitions of your paintings. Can you speak a little about the cultural whirlwind of that heady period?

PM: In hindsight, we were driven by an apocalyptic wind. Vietnam was in full swing and deeply disturbing. Then, the assassinations of 1968 [Martin Luther King Jr., Bobby Kennedy] poured gasoline on the fire. I remember the huge headline in the Evening Standard, with a photo of Bobby Kennedy, bleeding on the floor of the Ambassador Hotel: OH NO! NOT AGAIN! Nixon was an extremely polarizing figure. The sixties were like that. The more extreme things became, politically, the more that artistic work, in all media, erupted.

My major local contribution was a collaboration with Martin Sharp, with whom I was living at the time, on the ‘Magic Theatre’ issue of Oz. Martin’s idea was to basically make an all-visual issue – with no articles. It became a visual time capsule of the period, and it is widely regarded as a standout item of the period. We worked all hours collating, cutting and making each page a collage. Max Ernst and John Heartfield were inspirations – some of many.

SC: I re-watched your film Swastika (1973) recently. It is a deeply compelling documentary because it disrupts all the usual, well-worn tropes about Hitler. You present him as quite a banal and mundane human being, rather than a monster – and, in my opinion, this is a far more terrifying prospect! What was the reaction to the film on its release?

PM: Uproar! When it premiered at Cannes Film Festival, people fought in the audience and, for the first of many times, I thought it was my last film. I took off down the fire escape at the Cannes Palais but was stopped by PR film guru Pierre Rissient, who dragged me back for a very raucous press conference. Robert Hughes was there for Time magazine, and he gave a rousing defense of the film. Later, Laurence Durell congratulated me, and I had a rather perplexing conversation with a very sympathetic James Baldwin.

SC: In 1974, you co-founded Cinema Papers, a groundbreaking magazine which focused not only on international films but, equally important, on home-grown Australian cinema, which was then burgeoning into a real cultural force internationally. What was it about this period that allowed for such a flourishing of Australian cinema?

PM: It was a building momentum of young people who wanted to make films. The French New Wave was a worldwide inspiration for cinema lovers. It showed us that you could make a film cheaply. You didn’t need a chariot race, just a girl and a boy, or two boys and a girl. It was going to happen in Australia with or without the government help, which just rode the wave. I recall that Barry Jones and Philip Adams were powerful cultural figures, and they really got behind Australian film, which was great. The 10BA tax incentive, at the time, was also good, because you could make anything without absurd government/cultural evaluation. This resulted in piles of crap films, but also many fantastic films, which are now icons of Australian cinema. It all trained generations of actors and technicians. You were allowed to fail if you were an actor, but not if you were a director!

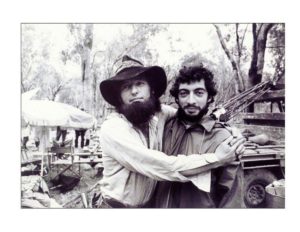

SC: Your film, Mad Dog Morgan (1976), is now rightly regarded as a classic of Australian cinema. Stories about the star, legendary American actor Dennis Hopper, abound. Could you give us a flavor of what he was like to work with?

PM: I got a hostile reaction from some quarters in Australia who hated Mad Dog Morgan. In fact, Ken Watts, the head of the Australian Film Commission at the time, said to my face that it would hurt tourism, and the government was funding films to help tourism. He particularly objected to the male rape of Dennis Hopper. It’s kind of sick, but it’s still OK to rape a woman in a Hollywood movie, but rarely a man.

For me, now, looking back, it is striking to think of all the things I didn’t have time to discuss with Dennis, in the blur of production. In retrospect, he respected me as an artist and as a painter, which I think made a big difference. I didn’t realize this at the time. He never mentioned that in his first starring role in Curtis Harrington’s Night Tide, the mermaid’s name is Mora. I never mentioned to him that I saw him In Gunfight at the OK Corral, and liked the film so much that I watched it four times in a row and my parents called the police because we had gone missing. I never realized until after I made Mad Dog that Dennis was in that film. If you look at Easy Rider and The Last Movie now, it is obvious to my eyes they were made by a painter. Dennis was a unique figure in Hollywood history, crossing over genuine art/Bohemia to mainstream Hollywood. He could drink with Ed Ruscha or John Wayne. He dressed like a cowboy in Taos, was shot at by Indians and loved the sexual paintings by D.H. Lawrence stacked in the local hotel. All this was a heady mix for me – a kid from Fitzroy Street, St Kilda.

The stories of his carousing in Australia are rather irrelevant to me now. Historically, millions of people have got trashed on absinthe, but there was only one Van Gogh. Ditto, millions of people took various substances in the sixties and seventies, but they didn’t make Easy Rider and change Hollywood forever. It’s sad that people want to pigeonhole an artist by highlighting their human weaknesses. I guess it makes them feel better in some way.

SC: You have spoken of your admiration for the work of Francis Bacon – in fact you describe Mad Dog Morgan as consisting of ‘Francis Bacon figures in a Sidney Nolan landscape’. What is it about his paintings that inspire you? Are there other painters you regard highly?

PM: Too many to list, really, but I would say that Picasso is still key to the Twentieth Century art. Then Marcel Duchamp and Jackson Pollock. Bacon is a late arrival, but his cinematic references and horrifying images took art out of the interior decorating business. This is ironic because Bacon had been an interior decorator of sorts. This may explain his ‘tasteful’ backgrounds. These walls of color, surrounding corpses, decay, carcasses and violence highlighted the horror. As a young artist, and child of Holocaust survivors, I found his art relevant in, for example, 1968, with the Vietnam war raging. The incredible photo of the naked little girl burned by napalm could have been painted by Bacon, in a good mood. Bacon’s use of Muybridge was also inspiring, since Muybridge was a film pioneer in many ways. I would speculate that without Bacon’s radical use of modern source-material we would not have Pop Art. He denied Pollock as decorative, but I think Pollock was important in his paintings, in that he captured real time – and time became a subject of his work.

SC: What are some of the projects you are working on at present?

PM: A virtual reality film called, Café Einstein, about the 1922 eclipse, which, when photographed in Western Australia, proved Einstein’s theory. I’m also working on [documentary] The Mystery of the Reclining Nude.

SC: Could you give us a few of your favorite films, by other directors?

PM: Because I am also a painter, or artist, or whatever you want to call it, I have a special affection for kitsch movies about artists, such as Lust for Life, with Kirk Douglas playing Van Gogh (Spartacus paints the sunflowers!); Moulin Rouge by John Huston, was also good in that genre. Picasso painting with light is an interesting short film, as is the short film of Jackson Pollock painting – or dripping – LIFE magazine called him ‘Jack the Dripper’, which made him famous, but he died soon after. Orpheus Testament by Jean Cocteau; North by Northwest, by Alfred Hitchcock; Hellzapoppin; any Godard movie; any Fellini movie: any Kubrick movie; The Fountainhead by King Vidor; To Be or Not to Be by Ernst Lubitsch; Blazing Saddles by Mel Brooks; any Buster Keaton film: The Nutty Professor, by Jerry Lewis; Persona by Ingmar Bergman.