The Rise and Fall of a Small Film Company (a.k.a. Grandeur et Decadenced’un Petit Commerce de Cinema), from 1986, never received a release in theatres, in part because it was made for French television but also due to fears by distributors following the controversy and protests over Hail Mary, Jean-Luc Godard’s “blasphemous” 1985 feature. Yet, the director’s follow-up venture was much less overtly edgy: As if to make up for Hail Mary, a deliberately provocative critique of the Catholic Church, The Rise and Fall of a Small Film Company is comparatively light, quirky and insular, at least in its initial portions. In fact, the maverick filmmaker seems to be poking fun at his late French New Wave friend and rival, François Truffaut, by creating his own version of Day for Night (1973), an alternately witty and sentimental ode to the movie business but one that Godard himself detested.

Godard’s screenplay starts out as one of his least original—the story of the difficulties of making a movie (this one supposedly based on a crime novel by James Hadley Chase). Unlike Day for Night‘s film-within-the-film, the Rise and Fall production is small-scale, penny-pinching and planned for television. On the other hand, the Truffaut comparison is still apt: from the casting of Truffaut alter-ego Jean-Pierre Leaud (here, as the movie company’s director) to the multiple references to American pop culture, including songs on the soundtrack by Janis Joplin and Bob Dylan and movie chatter about Rocky IV!

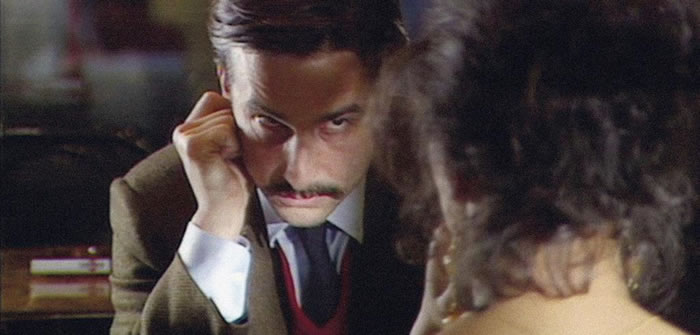

Yet, as Rise and Fall progresses, the story becomes less important while the Godard style and themes dominate. Leaud’s frazzled auteur (named Gaspard Bazin, a tribute to André Bazin, Godard’s Cahiers du cinema mentor) begins the process of auditioning extras while his business partner, Jean Almereyda (Jean-Pierre Mocky), seeks funding from mysterious and potentially dangerous foreign investors. Meanwhile, Almereyda’s wife, Eurydice (Maria Valera), decides to audition for the new film, putting Bazin in a bind about the conflict of interest.

Godard’s set-pieces overwhelm the second half of Rise and Fall with the kind of poignancy and insight that inform some of his best works, including Contempt, his own 1964 take on both the wonder and the sordidness of the industry and another film laced with allusions to Greek mythology. The early, ironically funny scenes of a waiter pitching a concentration camp drama to Bazin while his producer, Almereyda (the story’s Orpheus stand-in), is away begging for money from shady German characters yield to a more sober meditation on the brutal absurdity of art’s inevitable clash with commerce.

The lengthiest section that reflects upon structural inequities centers around a group of extras filing through a door as their stoic audition “readings” are limited to mere single words, with some individuals not allowed to speak, and all ultimately drowned out by Arvo Part’s melancholic scoring. Godard drives home the point with the haunting and haunted direct-address stare of the undeserving “star” Eurydice superimposed over these underpaid performers as she is allowed to give an expressive reading, and by juxtaposing shots of the company accountants figuring out the bit players’ meager earnings.

Elsewhere, Godard does not ignore Valera’s Eurydice and her feelings of marital and professional entrapment (expressed through prison-bar imagery and echoing the Orpheus myth at the climax). The director’s own cameo at a key late stage is surprisingly touching, not played for obvious laughs.

What is missing for Godard enthusiasts are those moments of rich aesthetic alchemy—notably, the coffee cup that becomes the Milky Way galaxy in Two or Three Things I Know About Her (1967) or the lyrical bicycle ride that highlights Every Man For Himself(1980). It should not be lost on anyone that Godard was limited by the very budget for Rise and Fall he self-reflexively mocks throughout the narrative.

Though seemingly less complex than other Godard projects, particularly the ones of recent years, and while fans eagerly await the director’s latest, The Image Book, The Rise and Fall of a Small Film Company proves itself to be a scaled-down version of what so many of his films are: cinematic essays about people, industries and societies at agonizing, existential crossroads. The 1980s technology represented may be dated, but the ideas and repercussions are not.

By Eric Monder for Film Journal International