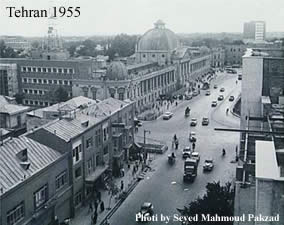

I started working as a construction worker at the age of six. I was working along with ten other workers building a housing project in a Tehran suburb. My life was limited to carry red bricks for other workers; I was carrying bricks from dawn to sunset and even in my dreams. The only joy of my life was listening to the stories of Mashdi, an old worker. Mashdi loved to tell us the stories of his old days working in the movie theaters. During the silent movie era, he had worked as an interpreter of the captioned text for the audience in the theaters, sometimes even describing the action. He wielded a long, white pointer which he used to identify the character on screen who was talking, invariably in a loud baritone voice! Often he would walk down the aisles hollering at the rowdy audience to “shut up!” Sometimes he would cradle blubbering infants while their mothers visited the rest room.

I started working as a construction worker at the age of six. I was working along with ten other workers building a housing project in a Tehran suburb. My life was limited to carry red bricks for other workers; I was carrying bricks from dawn to sunset and even in my dreams. The only joy of my life was listening to the stories of Mashdi, an old worker. Mashdi loved to tell us the stories of his old days working in the movie theaters. During the silent movie era, he had worked as an interpreter of the captioned text for the audience in the theaters, sometimes even describing the action. He wielded a long, white pointer which he used to identify the character on screen who was talking, invariably in a loud baritone voice! Often he would walk down the aisles hollering at the rowdy audience to “shut up!” Sometimes he would cradle blubbering infants while their mothers visited the rest room.

The advent of the “talkies” not only left a lot of Hollywood actors with bad voices unemployed, it also forced the golden-tongued Mashdi out into the street. But, within a few years, he returned to the movie house, this time playing harmonica and tap dancing in Fred Astaire style before the show started. Audiences delighted in his antics, but eventually the greedy theater owners cut the fun short in the name of profit and forced his musical career to an abrupt halt.

His love turned to hate, and now he repeatedly warned me not to get caught up in the movie business or even see a movie. He considered it was work for Gypsies. I still remember him declaring, “You will be damned to live under an evil spell. You will forget everything about the real world and real people. Your life will exist only on the thin silver screen…”

I still remember him declaring, “You will be damned to live under an evil spell. You will forget everything about the real world and real people. Your life will exist only on the thin silver screen…”

Mashdi-Mamad was the only worker among us, other than myself, who had an education. I was in my last year of elementary school when I learned that Mashdi, like many men of his generation, regularly wrote poetry. Unfortunately, I can only remember a fragment of one of his poems:

You ask me, my friend,

“Who will walk in this room?

Who will look out of this window?

Who will dance in this hall?”

My answer is simple,

“We build the houses

We will never live in”

Even after Mashdi died on a rainy winter afternoon, the indignity of his life lingered. To my surprise his only will was for me to spend all his fortune, that was about 10 Rials, on buying a movie ticket and watching the first movie of my life. Due to the poverty he worked so hard to overcome, he left this world penniless. So, we were forced to bury him in a used grave! Mashdi never had much that he could call his own; even in death had to share a tombstone, using the name on it as a kind of nickname.

Even after Mashdi died on a rainy winter afternoon, the indignity of his life lingered. To my surprise his only will was for me to spend all his fortune, that was about 10 Rials, on buying a movie ticket and watching the first movie of my life. Due to the poverty he worked so hard to overcome, he left this world penniless. So, we were forced to bury him in a used grave! Mashdi never had much that he could call his own; even in death had to share a tombstone, using the name on it as a kind of nickname.

That evening I thought I could only show my respect to Mashdi by going and watching the first movie of my life with my inheritance. So one Friday, after collecting my salary, I went to my first movie. I think it was a Laurel and Hardy comedy. I spent what remained of my wages on two celluloid frames – close-ups – one from a Douglas Fairbanks movie and the other one Esther Williams. Back in those days in Iran, before it was popular among French film fans to collect movie posters, we coveted our little frames of 35 millimeter celluloid.

celluloid.

When the contractor of the construction project learned of my adventures, he got very angry. He said I am a bad influence as I have wasted my time watching lies and he confiscated my little treasures, tossed them into the fireplace and fired me on the spot. Cruel, I remember thinking. Why punish poor Douglas and Esther? But their ashes brought me luck.

Within two days I was busy selling sandwiches, cookies and cigarettes to the drunkards and prostitutes who frequented the midnight show at an open air theater. It was a part time job, you understand, but no easy task to deal with such tough customers. But I was in heaven, able to savor the sweet pleasure of being able to watch the same movie every night for a month. It was well worth the trouble.

It was there that I discovered I had a talent for interpreting film. Every evening after sunset, when the first show began, I gathered the street kids around me: the beggars, the pickpockets, the factory workers and cleaning boys, those who could not afford the price of admission. And while they watched the screen from the street, I performed the dialogue, the music and the sound effects for them. Each of them paid me a penny.

It was there that I discovered I had a talent for interpreting film. Every evening after sunset, when the first show began, I gathered the street kids around me: the beggars, the pickpockets, the factory workers and cleaning boys, those who could not afford the price of admission. And while they watched the screen from the street, I performed the dialogue, the music and the sound effects for them. Each of them paid me a penny.

But my best customers were the blind beggar boys who paid me double for an exclusive show. You see, they demanded more–that I explain what was happening visually, as well as supplying the dimension of sound. I’ll admit now that I was not always faithful. Often I changed the ending from tragedy to a happy one, just to see the smiles on their faces.

It was not long before I encountered Misha-Dracula, the vampire projectionist of the open air theater. He was a middle-aged Armenian who spent most of his time in a drunken stupor. Many years before, while showing “Nosferatu” over and over again for several months, he came to believe that he himself was, in fact, a prince of darkness. He developed an aversion to garlic and the sign of the cross, while his reflection, so he swore, disappeared from every mirror. At least, he was unable to recognize his own reflection. Whenever asked why, if he was in fact a real vampire, he did not drink blood, he would wearily reply that he had lost his appetite.

Misha, who lived in the projection booth, provided hours of amusement each day for the otherwise bored street kids. First, they amused themselves by throwing cloves of garlic into his small room. When he would appear at the window to yell and frighten them away, the kids would wiggle shards of broken mirror reflecting sunshine into his face and making the sign of the cross with their fingers, laughing at his dramatic responses.

sunshine into his face and making the sign of the cross with their fingers, laughing at his dramatic responses.

I will admit that I, too, joined in these pranks -at least once. But, the sight of Misha quietly crying to himself caused something inside of me to snap. At that instant I began to fight the other kids back with a kind of holy vengeance. It was then that the games ended forever.

Like the young boy in “Cinema Paradiso”, I was fascinated by the projection booth. One day, while prowling around inside the small room, examining the equipment, I came face to face with the monster himself. I immediately offered him my blood –if only he will teach me his trade.

Count Misha replied that, according to a vampire’s code of honor, he could never drink the blood of a child. But, in return for the favor of driving away the annoying street kids, he would teach me how to “light up the screen.” It was in this way that we became life long friends.

During the winter months, the open air theater was held inside a large tent, the frigid air warmed by an old coal fired stove. However, it never really got warm enough to be comfortable, so the only patrons were usually drunkards who would gather around the stove, make tea and watch “Stagecoach” or “The Ten Commandment”. These were routine winter favorites.

To be continued….

“I Remember Cinema is written based on collective memories of my friends and myself, mixed with dreams, fantasies, facts and history.”