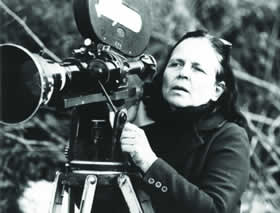

Bulgarian director Binka Zhelyazkova (born 1923) never shrank from controversy. Educated at Moscow’s prestigious film academy, she clashed with Bulgaria’s commissars and was at the forefront of political cinema under the country’s Communist regime. Intense and passionate about moviemaking as much as about her view of the society she lived in, Binka was ahead of her time. This documentary brings to light the woman behind the camera, and combines scenes from Binka’s films, rare archival footage, and candid interviews with former Bulgarian studio executives and film professionals. Her allegorical and urban dramas examined human rights, artistic freedom and the legitimacy of the political system itself.

Bulgarian director Binka Zhelyazkova (born 1923) never shrank from controversy. Educated at Moscow’s prestigious film academy, she clashed with Bulgaria’s commissars and was at the forefront of political cinema under the country’s Communist regime. Intense and passionate about moviemaking as much as about her view of the society she lived in, Binka was ahead of her time. This documentary brings to light the woman behind the camera, and combines scenes from Binka’s films, rare archival footage, and candid interviews with former Bulgarian studio executives and film professionals. Her allegorical and urban dramas examined human rights, artistic freedom and the legitimacy of the political system itself.

Elka Nikolova, director of “Binka: To Tell a Story about Silence”, served as Program Coordinator for the 2nd Bulgarian Film Festival, NYC (2001), and worked as an Associate Producer at Great Jones Productions in NYC. Currently she works as an Associate for Dateline NBC and The Today Show in New York. She studied film production at The New School University, New York, completing her MA in Media Studies in 2001. From her Master`s thesis, Women Directors on Women in Bulgarian Cinema, she developed the concept for a documentary about Binka Zhelyaskova.

Bulgarian Film Festival, NYC (2001), and worked as an Associate Producer at Great Jones Productions in NYC. Currently she works as an Associate for Dateline NBC and The Today Show in New York. She studied film production at The New School University, New York, completing her MA in Media Studies in 2001. From her Master`s thesis, Women Directors on Women in Bulgarian Cinema, she developed the concept for a documentary about Binka Zhelyaskova.

For more information about Elka and her movies please go to: www.binkadoc.com

Cinema Without Borders: How did you get inspired to make a documentary about Binka Zhelyazkova?

Elka Nikolova: What inspired me to make a film about Binka Zhelyazkova were her story and her cinema. When I left Bulgaria in 1994, the country was just beginning on the road to a very difficult and painful transition. Everything connected to communism was rejected and everyone wanted to begin anew. When I arrived in NYC I r ealized that if anything, the communist regime had managed to isolate Bulgaria to the point that it had lost its identity. Nobody here knows where Bulgaria is, not to talk about its culture and people. I felt as I had lost my identity as well and felt lost. I was born and grew up during the communist period and now all this was totally rejected. It felt as if the 27 years of my life didn’t exist and didn’t have any value and I had to start everything from the beginning. When I first saw Binka Zhelyazkova’s films and learned about her personal story I immediately saw something that I had long been looking for. Here was a woman and a filmmaker who had lived and worked during the communist period and had done good quality work, had been innovative, and whose work went beyond the local and the provincial forms, to reach higher grounds. For me that was enough to begin work on this documentary. I had found something of value in the thicket of all the rejection and negativity and I held onto it with a firm grip. Because for me it was important as a filmmaker and a human being to sustain myself by learning about Binka’s story and to be able to tell it at the end. It somehow reaffirmed my personal story. It didn’t matter that there were so many naysayer, so much rejection. I don’t think people are ready yet to reevaluate the communist period and see the good as well as the bad. But for me it’s been important that I start right away, before going on to work on anything else. I find some irony in that Binka Zhelyakzova was not able to participate in the film. For a few years now she has been overtaken by Alzheimer’s disease, the terrible disease of the mind. I had to intuitively navigate through the stories people told me about her: about her minimalism, her stubbornness, her romantic notion of cinema—and be able to intuitively sense who Binka really was. I wanted to make a positive film about an artist who has managed to defy the system, which she worked in, in her own way. In the end, it is a film about the endurance of the human spirit in times of turmoil.

ealized that if anything, the communist regime had managed to isolate Bulgaria to the point that it had lost its identity. Nobody here knows where Bulgaria is, not to talk about its culture and people. I felt as I had lost my identity as well and felt lost. I was born and grew up during the communist period and now all this was totally rejected. It felt as if the 27 years of my life didn’t exist and didn’t have any value and I had to start everything from the beginning. When I first saw Binka Zhelyazkova’s films and learned about her personal story I immediately saw something that I had long been looking for. Here was a woman and a filmmaker who had lived and worked during the communist period and had done good quality work, had been innovative, and whose work went beyond the local and the provincial forms, to reach higher grounds. For me that was enough to begin work on this documentary. I had found something of value in the thicket of all the rejection and negativity and I held onto it with a firm grip. Because for me it was important as a filmmaker and a human being to sustain myself by learning about Binka’s story and to be able to tell it at the end. It somehow reaffirmed my personal story. It didn’t matter that there were so many naysayer, so much rejection. I don’t think people are ready yet to reevaluate the communist period and see the good as well as the bad. But for me it’s been important that I start right away, before going on to work on anything else. I find some irony in that Binka Zhelyakzova was not able to participate in the film. For a few years now she has been overtaken by Alzheimer’s disease, the terrible disease of the mind. I had to intuitively navigate through the stories people told me about her: about her minimalism, her stubbornness, her romantic notion of cinema—and be able to intuitively sense who Binka really was. I wanted to make a positive film about an artist who has managed to defy the system, which she worked in, in her own way. In the end, it is a film about the endurance of the human spirit in times of turmoil.

CWB: What does “Binka: To Tell a Story about Silence” focus on? On her political life, or her life as an artist?

Elka: The focus of the film is on Binka, the artist. It is very important to emphasize that. When and where Binka Zhelyazkova worked was just the background, which I used to frame her story and her dilemma as an artist working in a very complicated times. It is most gratifying for me when filmmakers and artists come to me and say: I can identify with her story. Because we all as artists struggle to make our best work, and many times we have to compromise in order to even be able to finish what we have started, regardless of our circumstances: economical, political, cultural. Binka Zhelyazkova did her best to remain truthful to her ideals and her vision and to maintain her dignity as a filmmaker in politically very charged times.

CWB: How challenging was it to make this documentary and to find the resources you needed?  Elka: It was really challenging to make the film not only financially but because it was hard to make people see the value of the story. Here in the US people thought that this was an obscure story, that it would not be interesting to many people: after all let’s face it—Who would be interested in a woman filmmaker from a small former communist country nobody has heard of? And in Bulgaria, the film community perceived me as an outsider and for the longest time was suspicious of my intentions. Once that was taken out of the way the funding came through. I raised some money through private donors and finally got the grant from the National Film Center in Bulgaria, which made it possible to complete the film.

Elka: It was really challenging to make the film not only financially but because it was hard to make people see the value of the story. Here in the US people thought that this was an obscure story, that it would not be interesting to many people: after all let’s face it—Who would be interested in a woman filmmaker from a small former communist country nobody has heard of? And in Bulgaria, the film community perceived me as an outsider and for the longest time was suspicious of my intentions. Once that was taken out of the way the funding came through. I raised some money through private donors and finally got the grant from the National Film Center in Bulgaria, which made it possible to complete the film.

CWB: Binka, like yourself, was a woman filmmaker, has this been a motive for you to make “Binka?”

Elka: The fact that Binka is a woman filmmaker was part of my motivation to make the film, yes. I identified with her and I wanted to explore her experiences because I wanted to see how things have changed for women of her generation and mine. Some things are very different. The good thing is that there are more women making films today than when Binka was making films. Her work made it easier for many of us. But the difference is that even though there are many more women making films, few of them are making big budget feature film, the way Binka did, simply because she was part of the government owned studio system. She had the chance to work on films with big crews and big budgets with complex sets something that very few of us have the chance to do today. But I remain hopeful for the near future.

CWB: How important is for the Bulgarian young generation who have no memory of the communist era to see this documentary?

Elka: I think it is very important. This was a period in our recent history which lasted almost 50 years and many people are still affected by it. Without even knowing it the younger generation is influenced by it—because they are being raised by parents who grew up in that system. When we were growing up we didn’t know anything about the real problems, which were facing our society because the propaganda machine fed us lies. So I guess we all, together, can learn the truth about the communist period and move on. I think that is healthier than totally denying its existence or pretending it never happened.

CWB: What has been the reaction of those in the older generation who have seen the “Binka” doc?

Elka: The people who saw the film in Bulgaria were grateful that a film about Binka Zhelyazkova was finally made. I think the fact that it was made by somebody of my generation was significant because we didn’t truly participate in the key events but still grew up in the system so we have both perspectives. Some people cried, others debated weeks after seeing the film. One man, a screenwriter, met me on the street and said to me—I have changed my opinion about Binka after seeing your film, now I can understand her and her actions much better. Very few people knew the background story of Binka’s life, the problems she had with the censorship and the ban against distribution of her films. The fact that she was a member of the communist party was what people mostly know about her. She didn’t like to be out in the public, she never gave interviews for TV or radio. But I think it is good to know that people like her existed in a period where it looked like everybody was conforming to the accepted rules. That gives me hope because If we find more people like her we can have something to hold onto for the future.

CWB: “Binka” is scheduled for a screening at Southeast European Film Festival in Los Angeles, what do you think about this opportunity?

Elka: I am really happy to screen my film at the South East European Film Festival, because it will be part of group of films from the same part of the world and this way the film can be seen in context. Also, Binka Zhelyazkova loved American films. We Were Young, her 1961 feature for example was very much influenced by the American classic The Best Years of Our Lives. She also loved jazz and listened to it all the time. This way even indirectly she was connected to American cinema and Hollywood.

CWB: What was your inspiration to become a filmmaker?

CWB: What was your inspiration to become a filmmaker?

Elka: When I finished school I was not sure what I wanted to do. I was never one of those people who knew when they were six that they would be a filmmaker when they grew up. I studied psychology in college but ended up not wanting to continue in that field. Then I started taking anthropology classes and then traveled to remote mountain villages in South Bulgaria. I worked on a documentary film about a small multi-ethnic community, shot some video and one day played that back to the local people. They liked the video so much they played it in the village bar all the time. I realized how powerful the medium was and I also felt more passionate for what I was doing than ever before. When I moved to New York, I decided to go back to school and study film.

CWB: Who are the filmmakers that you admire?

Elka: I love the American classics, the screwball comedies, my favorite is “Some Like It Hot” but also the films of the sixties and the seventies for all the experimentation with the sound and the picture. Of course I very much admire Bunuel’s “The Exterminating Angel”, Antonioni’s “Blow Up”; Hitchcock’s “Rear  Window”, Coen Brothers’ “Fargo”, Sally Potter’s “Orlando”, Binka Zhelyazkova’s “The Attached Balloon” and Tarkovsky’s “Stalker”. These are just some of my all-time favorite films and directors, who I admire and have influenced me.

Window”, Coen Brothers’ “Fargo”, Sally Potter’s “Orlando”, Binka Zhelyazkova’s “The Attached Balloon” and Tarkovsky’s “Stalker”. These are just some of my all-time favorite films and directors, who I admire and have influenced me.

CWB: Please tell us about your future projects.

Elka: I am working on the idea for another documentary film, while collecting stories for a feature film. I am exploring the idea of making a film about artists from Bulgarian descent who have long immigrated from Bulgaria and have completely immersed themselves in the American way of life. Through making the documentary film about Binka I have met a number of very inspiring people who have given me a lot of support simply because they understood my need to make this film. They are very positive people and that fascinates me because they themselves have gone through many difficulties and yet have such a positive outlook on life.

CWB: Thank you for your time.