A contributing writer for The New York Times, James Ulmer’s 20-year journalistic career has included eight years as international editor and columnist for The Hollywood Reporter, where he reported from the world’s leading film festivals and markets and supervised a fleet of 35 foreign correspondents. For Premiere magazine, he penned the national columns “James Ulmer’s World View” and “Rank and Bank – The Ulmer Scale.” He has also written for The Los Angeles Times, Variety, Directors Guild Quarterly, Movieline and The Observer in London.

A contributing writer for The New York Times, James Ulmer’s 20-year journalistic career has included eight years as international editor and columnist for The Hollywood Reporter, where he reported from the world’s leading film festivals and markets and supervised a fleet of 35 foreign correspondents. For Premiere magazine, he penned the national columns “James Ulmer’s World View” and “Rank and Bank – The Ulmer Scale.” He has also written for The Los Angeles Times, Variety, Directors Guild Quarterly, Movieline and The Observer in London.

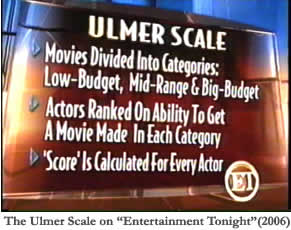

Ulmer has been interviewed in numerous national publications, including The New York Times Magazine, The Wall Street Journal, Newsweek, The Los Angeles Times, Detour, Talk Magazine and Variety. He has appeared frequently on network and syndicated televisions shows such as “Entertainment Tonight,” “CBS This Morning,” “CNN Showbiz Today,” The Reelz Channel, Voice of America, and on the HBO, BBC, Fox and E! Networks. For six months he was a featured commentator on E!’s top-rated “The Gossip Show,” joining Liz Smith, Army Archerd and others. Most recently, Ulmer served as a media writer for PriceWaterhouseCoopers and was as a senior analyst and executive producer for the Internet company Creative Planet.

For the film industry, Ulmer publishes his popular Actors Hot List and Directors Hot List, which have become the industry’s most reliable and comprehensive tools for measuring the global value of stars and directors in a variety of areas. These include bankability, career management, professionalism, promotion, risk factors and talent. He also consults regularly on risk assessment strategies for the professional film investor.

Ulmer is also the author of James Ulmer’s Hollywood Hot List – The Complete Guide to Star Ranking published by St. Martin’s Press. Dubbed “the industry bible  of star power” by the New York Post, this 300-page book features power rankings and tribal wisdom on the top 200 stars, and lively chapters on the behind-the-scenes world of Hollywood stardom.

of star power” by the New York Post, this 300-page book features power rankings and tribal wisdom on the top 200 stars, and lively chapters on the behind-the-scenes world of Hollywood stardom.

As an undergraduate at Harvard, Ulmer directed plays by Moliere and Shakespeare and was an editor of The Harvard Crimson. After graduation, he worked with the ABC White House press corps before moving to London, where he wrote and directed the documentary “Lost Property” for the BBC.

In addition to reporting, Ulmer has regularly spoken on the film industry at international film festivals and markets. He has been nominated for a Press Award by the Publicists Guild of America and served on the competition jury for the Cairo International Film Festival. He is currently working on book and a documentary about politics in Hollywood.

Bijan Tehrani: I know that your relationship with Vera Mijojlic, president of the Southeast European Film Festival goes back to the “Sarajevo project” days, tell us more about it please.

Bijan Tehrani: I know that your relationship with Vera Mijojlic, president of the Southeast European Film Festival goes back to the “Sarajevo project” days, tell us more about it please.

James Ulmer: Yeah. It was a few years ago and Vera and I are kind of like two parts of the same root of a plant. We soak up stuff from the same soil, which is international film festivals and our love of movies. So she came to me, really—and I’m terrible at remembering the exact times and everything—but she came to me with an idea that she was very passionate about, which was about the need in this time of life to share international stories and to use cinema as the medium. We decided that we needed to formalize that and put it into some kind of…Film Caravan, and that’s what it was originally called. Originally it was going to be taking place in Belgrade and in America. She and I would meet over coffee and would meet in different places and she was dealing with a couple of other people as well but she and I had really started chipping away at this wonderful idea. We had the idea that maybe we would actually take a little bus all around Yugoslavia and  into each of these little towns, bring in people like a caravan to help make a film and at the end of that trip we would have made a complete film and gathered, like a Pied Piper, all of these people; people from different parts of town that wanted to make a film would be invited to come with us to make a film and the actual filmmaking materials might be within the bus. There actually was inspiration for this by a kid who was working in Venice who was doing the same thing. From that—so we had a lot of different expressions of what we wanted to do—we wrote a manifesto. It was a manifesto that said exactly what we wanted our film festival, at that point, to be. And, with a manifesto, you need people to sign it, so we got together a group—it was a lot of Vera’s contacts of people from all over the world

into each of these little towns, bring in people like a caravan to help make a film and at the end of that trip we would have made a complete film and gathered, like a Pied Piper, all of these people; people from different parts of town that wanted to make a film would be invited to come with us to make a film and the actual filmmaking materials might be within the bus. There actually was inspiration for this by a kid who was working in Venice who was doing the same thing. From that—so we had a lot of different expressions of what we wanted to do—we wrote a manifesto. It was a manifesto that said exactly what we wanted our film festival, at that point, to be. And, with a manifesto, you need people to sign it, so we got together a group—it was a lot of Vera’s contacts of people from all over the world  including Korea, parts of Asia, and everything—and they gathered at my house and Vera was very fond of calling it “The Declaration of Independence” or declaring it as our “Manifesto” and it was a very wonderful, wonderful meeting. We all signed the manifesto, we went through many different drafts, and it was a real passion. From that seed, Vera put together a board and other folks and we all met many times and we actually threw the first festival all due to Vera’s incredible commitment and passion. A few years ago, the first See Film was screened in Beverly Hills and, even though it was just a start-up festival, she had already made alliances with Goethe Institute and it was quite a great success. Yes, there are always some problems because it’s enormously complex, even for a few films. To get the Visa clearance and the directors—some of whom weren’t

including Korea, parts of Asia, and everything—and they gathered at my house and Vera was very fond of calling it “The Declaration of Independence” or declaring it as our “Manifesto” and it was a very wonderful, wonderful meeting. We all signed the manifesto, we went through many different drafts, and it was a real passion. From that seed, Vera put together a board and other folks and we all met many times and we actually threw the first festival all due to Vera’s incredible commitment and passion. A few years ago, the first See Film was screened in Beverly Hills and, even though it was just a start-up festival, she had already made alliances with Goethe Institute and it was quite a great success. Yes, there are always some problems because it’s enormously complex, even for a few films. To get the Visa clearance and the directors—some of whom weren’t  allowed to leave their countries—and the films, I’m amazed at how Festivals are done anyway but she really took this on with Nenad Dukic, who used to be my Yugoslavian bureau chief when I was International Editor of the Reporter. I would have these thirty-five guys all over the world that I would have to look after but Nenad was probably the most intellectual of them all. You know, he was the most film-literate of all of my correspondents so I always had a fondness for him because of that. I used to teach film as a T.A. at Harvard; a Teaching Assistant in the History of Film Class at Harvard with Dr. Vlada Petric, who remains one of my closest friends. So he was Slavic too and there has always been a great connection I have had with that part of the world and this was just formalizing that.

allowed to leave their countries—and the films, I’m amazed at how Festivals are done anyway but she really took this on with Nenad Dukic, who used to be my Yugoslavian bureau chief when I was International Editor of the Reporter. I would have these thirty-five guys all over the world that I would have to look after but Nenad was probably the most intellectual of them all. You know, he was the most film-literate of all of my correspondents so I always had a fondness for him because of that. I used to teach film as a T.A. at Harvard; a Teaching Assistant in the History of Film Class at Harvard with Dr. Vlada Petric, who remains one of my closest friends. So he was Slavic too and there has always been a great connection I have had with that part of the world and this was just formalizing that.

Bijan: I know you have always been interested in International Cinema. How did that interest start?

Bijan: I know you have always been interested in International Cinema. How did that interest start?

James: One word: Fellini. Mine started with Fellini. I lived in Italy when I was 14 and I had a love for that Italian openness. Then I went to Harvard and, in those days, Harvard Square was filled with Art Cinemas—this was in the early 80’s—and they still existed; there were nine of them within a stone’s throw of my dorm in Harvard Square, now they don’t exist anymore. So I was constantly going to cinema and I saw all of the Fellini, all of the Truffaut, and all of the Bergman. Really, we didn’t see much of the Asian except for Kurosawa and I didn’t see any Iranian movies but I saw all of the European films and, so, that started that. Then I traveled; I’ve always been traveling overseas. I think somebody infected me with a Gypsy-virus because that’s all I do; I love traveling to Film-festivals and I covered them for 10 years at the Hollywood Reporter as the International Editor.

Bijan: Do you think that international movies are becoming more popular than a decade ago in US?

James: They are, but that’s partly because it’s niche-marketing and niche-marketing, as a rule, has become a lot  more successful in America; general marketing has not. In the general market, it’s still really just a ghetto. The foreign-film market is just 2% of the overall market but I had thought, in the 80’s when I was writing about the issue of what had happened to our love of foreign films, and I had written lots of columns about the fact that cable was coming up and we thought that cable, with all the different channels, could show foreign movies and it would affect the general market for foreign language films, and I still remain a pessimist in the sense that it hasn’t that much. But, those who want it now, who have developed that interest, can find it within that niche more exploding than ever. I think it’s terrible that you go to a film store out here and, you know…Cinemaphile, which is a great store. There is no reason why you should have to spend $29 to see a Kiarostami film on a CD. I’m sorry, that’s

more successful in America; general marketing has not. In the general market, it’s still really just a ghetto. The foreign-film market is just 2% of the overall market but I had thought, in the 80’s when I was writing about the issue of what had happened to our love of foreign films, and I had written lots of columns about the fact that cable was coming up and we thought that cable, with all the different channels, could show foreign movies and it would affect the general market for foreign language films, and I still remain a pessimist in the sense that it hasn’t that much. But, those who want it now, who have developed that interest, can find it within that niche more exploding than ever. I think it’s terrible that you go to a film store out here and, you know…Cinemaphile, which is a great store. There is no reason why you should have to spend $29 to see a Kiarostami film on a CD. I’m sorry, that’s  just stupid. CD’s over there in Iran or wherever a person is from, you should be able to make it and download it in America. I’m not talking about pirating, but this is the problem: we are working on a prejudice which is a financial prejudice against a foreign market because all of their movies are so expensive. So, that’s a market problem. If they were $5 or $6 like the crap movies that you see in America….it’s like junk food is cheap, good food is more expensive. But there is no reason, when it’s a digital world, that we should be paying these prices. Most of the kids now and people that watch foreign movies will see them on digital, they will not see them in motion picture, and I’m all in favor as that. I don’t care really, so long as it’s an excellent screening. Put ‘em on your wall, watch them anywhere! I’m not a fascist when it comes to screening materials; just introduce people to foreign movies. Take them in a bus, go around the neighborhood, you know?

just stupid. CD’s over there in Iran or wherever a person is from, you should be able to make it and download it in America. I’m not talking about pirating, but this is the problem: we are working on a prejudice which is a financial prejudice against a foreign market because all of their movies are so expensive. So, that’s a market problem. If they were $5 or $6 like the crap movies that you see in America….it’s like junk food is cheap, good food is more expensive. But there is no reason, when it’s a digital world, that we should be paying these prices. Most of the kids now and people that watch foreign movies will see them on digital, they will not see them in motion picture, and I’m all in favor as that. I don’t care really, so long as it’s an excellent screening. Put ‘em on your wall, watch them anywhere! I’m not a fascist when it comes to screening materials; just introduce people to foreign movies. Take them in a bus, go around the neighborhood, you know?

Bijan: Please tell us about your new documentary film project.

James: It’s now held up in England because we are working with Channel Four. It was supposed to have been with Martin Sheen, but Martin was simply too  exhausted to do it after having finished The West Wing series, and graciously declined, which was of course a disappointment because the entire documentary was dependent upon him. It was based on a story I did on the front page of Sunday New York Times about politics in Hollywood. Now I am exploring a medical miracle story, but it has politics and science and medicine and art, all combined; it’s a fascinating story. That’s the project that would be next and that’s something that I would shoot myself because I know that the guy over here at UCLA is behind it and it’s an extraordinary story that hasn’t been told. That’s not to do with international film; it’s just a love of digital shooting. I go over and I take digital photography whenever I go to a festival and I have hundreds of hours that I want to find a way to put on to my own website.

exhausted to do it after having finished The West Wing series, and graciously declined, which was of course a disappointment because the entire documentary was dependent upon him. It was based on a story I did on the front page of Sunday New York Times about politics in Hollywood. Now I am exploring a medical miracle story, but it has politics and science and medicine and art, all combined; it’s a fascinating story. That’s the project that would be next and that’s something that I would shoot myself because I know that the guy over here at UCLA is behind it and it’s an extraordinary story that hasn’t been told. That’s not to do with international film; it’s just a love of digital shooting. I go over and I take digital photography whenever I go to a festival and I have hundreds of hours that I want to find a way to put on to my own website.

Bijan: Are you still involved with the Southeastern Film Festival?.

James: Yeah, but only in an advisory capacity. Sure, I’m on the advisory board and I helped with publicity and things of that sort and, you know, anything that I can do for Vera, I will do it. I’ve worked with her interns a little bit but it’s not as much as I’d like. I’d like to devote more time to it, but I’ve got so many projects right now. But when it comes time and she asks me to do something, I do it.

Bijan: What are the movies that you like most?

James: Well, I’ll talk American independents. Little Children was a film that I thought was extraordinary. Internationally, there are lots of others. I loved the nomination from Mexico, Pan’s Labyrinth. Water was superb as well. It’s very hard I mean you know, I’ll tell you, Antonioni is probably one of my all-time favorites. I have a huge passion for Italian realists, neo-realists, I have to say. Also, to some extent, the French impressionists and the German expressionists—Nosferatu is great. It’s tough for me to answer that; I could go down and list you 150 movies.

Bijan: What are your favorite Neo-Realist movies?

Bijan: What are your favorite Neo-Realist movies?

James: Il Gattopardo, the Leopard. It’s extraordinary. Roma, città aperta , The Bicycle Thief, 8 1/2, Le Notte Di Cabiria, I Vitelloni, Ithey just keep going on. Giulietta degli Spiriti … There’s extraordinary Rossellini with his moving color constellations. Some wonderful French, I liked—some of the old Eric Rohmer and Truffaut films and Michel Carne. Probably one of my favorite films of all time is Les Enfants du Paradis. I mean, I go back to the historic and I still look back at those. There is also this fascinating new Russian director, young, that I can’t remember his name but I really, really liked and I have to get his name. He is only about 30 years old and he is terrific and just wonderful. And of course there’s Spain’s Alejandro Almenobar. So I try to see films and that’s when I go to Cannes to catch up.

Bijan: Than you James.