Lauded as one of America’s most gifted filmmakers, Charles Burnett has just completed his largest film ever, Namibia: The Struggle for Liberation. While earning his MFA in filmmaking at UCLA, Burnett made the now classic Killer of Sheep, and on that basis he was awarded the prestigious John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Fellowship (also known as the “genius grant”) with others to follow from the Guggenheim Foundation, the Rockefeller Foundation, the National Endowment for the Arts, and the J. P. Getty Foundation. He is also the winner of the American Film Institute’s Maya Deren Award and Howard University’s Paul Robeson Award for achievement in cinema. To Sleep with Anger won the 1991 Independent Spirit Award for Best Director and Best Screenplay for Burnett and Best Actor for Danny Glover, and the Library of Congress has entered it along with Killer of Sheep in the National Film Registry. Among his numerous films since then, Burnett has written and directed Nat Turner: A Troublesome Property, a splendidly mind-boggling work about history as interpretation, and also Warming by the Devil’s Fire, a sensual, quasi-autobiographical tale of an L.A. boy getting religion and the blues in the same visit back home to Mississippi.

Lauded as one of America’s most gifted filmmakers, Charles Burnett has just completed his largest film ever, Namibia: The Struggle for Liberation. While earning his MFA in filmmaking at UCLA, Burnett made the now classic Killer of Sheep, and on that basis he was awarded the prestigious John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Fellowship (also known as the “genius grant”) with others to follow from the Guggenheim Foundation, the Rockefeller Foundation, the National Endowment for the Arts, and the J. P. Getty Foundation. He is also the winner of the American Film Institute’s Maya Deren Award and Howard University’s Paul Robeson Award for achievement in cinema. To Sleep with Anger won the 1991 Independent Spirit Award for Best Director and Best Screenplay for Burnett and Best Actor for Danny Glover, and the Library of Congress has entered it along with Killer of Sheep in the National Film Registry. Among his numerous films since then, Burnett has written and directed Nat Turner: A Troublesome Property, a splendidly mind-boggling work about history as interpretation, and also Warming by the Devil’s Fire, a sensual, quasi-autobiographical tale of an L.A. boy getting religion and the blues in the same visit back home to Mississippi.

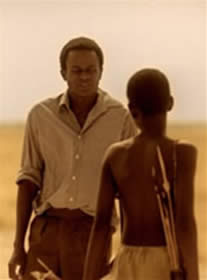

A starkly different venture nearly three hours long, Namibia: The Struggle for Liberation is an epic that spans 60 years of history with 150 speaking roles in multiple languages and dialects, dramatizing Namibia’s fight for liberation from South African occupation that culminated in Namibia’s independence in 1990. The cast includes Carl Lumbly and Danny Glover as well as local African actors, and the crew used former soldiers from both Namibia and South Africa who had fought against each other. I interviewed Charles Burnett in Westwood just following the film’s world premiere at the 2007 Los Angeles Film Festival.

with 150 speaking roles in multiple languages and dialects, dramatizing Namibia’s fight for liberation from South African occupation that culminated in Namibia’s independence in 1990. The cast includes Carl Lumbly and Danny Glover as well as local African actors, and the crew used former soldiers from both Namibia and South Africa who had fought against each other. I interviewed Charles Burnett in Westwood just following the film’s world premiere at the 2007 Los Angeles Film Festival.

Diane Sippl: Can you explain the genesis of the project?

Diane Sippl: Can you explain the genesis of the project?

Charles Burnett: It started with the government’s formation of PACON, the Pan-African Centre of Namibia, and their mandate was to do stories and themes in art works that dealt with Pan-Africanism. At the same time Sam Nujoma, the first President of Namibia and the former President of SWAPO (South West Africa People’s Organization), had just finished his autobiography called Nujoma: Others Wavered. Uazuva Kaumbi, the executive producer of the film, Namibia: The Struggle for Liberation, was on the board of PACON and suggested that they make a movie from the book.

They hired a Namibian first-time writer for the first screenplay and brought in a Nigerian to do a polish. Then they took the scri pt around looking for a director — Raul Peck was one — and they were looking for actors at the same time, believe it or not. They finally came around to me, and I read the scri pt and thought it was feasible. When I was going to school I was aware of SWAPO, so I was very excited about doing it.

Raul Peck was one — and they were looking for actors at the same time, believe it or not. They finally came around to me, and I read the scri pt and thought it was feasible. When I was going to school I was aware of SWAPO, so I was very excited about doing it.

But the scri pt had limitations; it was more or less a TV movie. It didn’t cover the whole movement of SWAPO. It was just based on the book and needed to be expanded. It was all about Nujoma and they wanted it to be more about the people of Namibia. So we expanded it into an epic story of the human struggle of people wanting to get out from under the yoke of colonialism and free of South Africa’s apartheid system.

The producers were supposed to find matching funds to support the production, but they never managed to do this, so the Film Commission, which is sponsored by the government, ended up financing the whole film. This cost about $10 million.

Diane: How did you research the rest of the fighters and the military operations? Charles: I used the book only chronologically and for details about Nujoma’s family that he knew a lot about. But historically, I wanted to find the real facts and not rely on his perspective. So I read a lot of books, and Isaac !karuchab, who was a member of one of the military arms of SWAPO, a PLAN (People’s Liberation Army of Namibia) fighter, gave me a lot of information about the war, the battles, the songs they sang, who was who, and he corrected some of the errors that were going around about what was true. We talked about the young people who were in exile, some in foreign countries going to schools, and some others who ended up in dungeons. It surprised me — some of their friends and family members were also in exile. It’s a part of history that isn’t talked about, and we just mention it in the film. And there were other stories like that, that were too complicated to get involved with due to the limits of the project.

Charles: I used the book only chronologically and for details about Nujoma’s family that he knew a lot about. But historically, I wanted to find the real facts and not rely on his perspective. So I read a lot of books, and Isaac !karuchab, who was a member of one of the military arms of SWAPO, a PLAN (People’s Liberation Army of Namibia) fighter, gave me a lot of information about the war, the battles, the songs they sang, who was who, and he corrected some of the errors that were going around about what was true. We talked about the young people who were in exile, some in foreign countries going to schools, and some others who ended up in dungeons. It surprised me — some of their friends and family members were also in exile. It’s a part of history that isn’t talked about, and we just mention it in the film. And there were other stories like that, that were too complicated to get involved with due to the limits of the project.

Diane: This is the first film of yours that at times uses lots of action and involves spectacle. It opens with a very long, wide shot of the man in the vastness of the land, and you keep it for awhile and return to it later. Is it related to your way of making an epic?

land, and you keep it for awhile and return to it later. Is it related to your way of making an epic?

Charles: Well I wouldn’t call this an “action film” as such because it’s not about that. It’s about a country, a people in conflict, trying to establish their rights as human beings, and it took a war to do so. It took an armed struggle, so there was action in that sense.

And this is living history, so it had to be exact, very accurate. There was no room for interpretation. Even though it’s a film, and there are some dramatic liberties, chronologically there are none. Everything had to be in place.

And it was a big picture. There were many battles and atrocities. The first one happened when women argued in front of a priest in his office about being forcefully moved, and a confrontation broke out and eleven people were killed. That led to the whole exile movement.

And then in Omugulu-gOmbashe insurgents fought South Africans for the first time in battle. And then came Kassinga and Cuito-Cuanavale — they’re all important battles, a lot of fight scenes, and they’re significant in terms of the outcome of this whole struggle. They’re not in there just for commercial appeal; they’re the key moments, and they are absolutely essential. And there are people who were there at the time, from the first massacre to Omugulu-gOmbashe to Kassinga and then to Cuito-Cuanavale. These people are still alive and they are very guarded about how you portray these scenes.

And then in Omugulu-gOmbashe insurgents fought South Africans for the first time in battle. And then came Kassinga and Cuito-Cuanavale — they’re all important battles, a lot of fight scenes, and they’re significant in terms of the outcome of this whole struggle. They’re not in there just for commercial appeal; they’re the key moments, and they are absolutely essential. And there are people who were there at the time, from the first massacre to Omugulu-gOmbashe to Kassinga and then to Cuito-Cuanavale. These people are still alive and they are very guarded about how you portray these scenes.

The character Danny Glover plays, Father Elias, is a composite of a number of Christian people who were very instrumental in helping the indigenous people of Namibia to sustain themselves. Namibia has been a very Christian country with a lot of Lutheran churches, and they played a big role in the struggle — something like the abolitionist movement in the United States. But people like Reverend Michael Scott were deported and not allowed back in South Africa. You see at the end of the film that he was a really important figure in terms of the United Nations. Father Elias is one of the reverends whose son is marching in the funeral. There were a lot of issues with priests who took a political stance and the government forcefully moved them to different areas like Ovamboland.

instrumental in helping the indigenous people of Namibia to sustain themselves. Namibia has been a very Christian country with a lot of Lutheran churches, and they played a big role in the struggle — something like the abolitionist movement in the United States. But people like Reverend Michael Scott were deported and not allowed back in South Africa. You see at the end of the film that he was a really important figure in terms of the United Nations. Father Elias is one of the reverends whose son is marching in the funeral. There were a lot of issues with priests who took a political stance and the government forcefully moved them to different areas like Ovamboland.

Diane: Isn’t spectacle powerful in making a film of this nature?

Diane: Isn’t spectacle powerful in making a film of this nature?

Charles: Well, I think so — when you know the history, when you are the people, here the Namibian people. They know about a massacre, so then they cry at it, and they know about Omugulu-gOmbashe and particularly Kassinga. It’s the way someone of the Jewish faith would look at the Holocaust, at Auschwitz and other places; they have particular meaning.

It’s not like an “action film” action film; it’s an historical event that has to be told. It’s part of their story, their history. And these events are very critical battle scenes, not just any battle scenes. There are others we could have used, but these were the most meaningful ones, the turning points.

Diane: In how many countries did you end up shooting?

Charles: We shot only in Namibia, but we shot all over Namibia. We were going to shoot in Cuba, in South Africa, Robben Island, and in New York. Well, we have New York in the film, but it was shot in Namibia. We took some stock footage, and for the U.N. we shot in Namibia’s Parliament, its government building.

Diane: Was it difficult working with the various languages? How does a filmmaker approach that situation? Not so many bother to take it on.

Charles: A lot of people in Namibia speak multiple languages, various tribal languages, or they speak Oshivambo, for example, but maybe not perfectly. Now this presents a problem in casting, because you ask the actor, “Can you speak Oshivanbo?” and he says, “Yes.” But then you find out he can’t. Or he speaks it, but he’s from the city, and in the countryside there’s a dialect, and it becomes an issue. We had a crew member who speaks Oshivambo who never caught that, but then people who watched the film did. We’d like to change it, but we can’t — it’s locked in.

You know we invited people to come in and see the dailies and make comments, and no one did. There’s a word or two in a song in the film that might sound derogatory about an Angolan child. They heard this song every day, and all of a sudden, to avoid conflict with their neighbors, they want it changed. This is after we mixed the film. Well, the train is at the station, you know…

derogatory about an Angolan child. They heard this song every day, and all of a sudden, to avoid conflict with their neighbors, they want it changed. This is after we mixed the film. Well, the train is at the station, you know…

But also with languages, there are certain words you can’t translate. Even in Afrikaans, we had this problem. For example, the language has no word for “humanitarian.” They have the word “philanthropical,” but not “humanitarian.”

Then there’s the slang. We wrote in the scri pt that a soldier’s sister was “pissed” because her husband joined the service, right? Well this meant “drunk” to the South Africans, so we needed to change it to “pissed off.”

Diane: You’ve worked with Carl Lumbly (who plays Sam Nujoma) and Danny Glover (who plays Father Elias) before, and you’re also working here with people who’ve maybe never acted in the cinema prior to this film. What was the give-and-take between the local actors and the international figures?

Diane: You’ve worked with Carl Lumbly (who plays Sam Nujoma) and Danny Glover (who plays Father Elias) before, and you’re also working here with people who’ve maybe never acted in the cinema prior to this film. What was the give-and-take between the local actors and the international figures?

Charles: First of all, any person in Namibia wanted to be in the film, to play a part, no matter what part, because they felt it was important. But during casting I was kind of worried, because they had the wrong idea of what it was about. The other thing is we had 150 roles or more that people were coming in for, and I couldn’t remember their names — they were really complicated for me, and some people were coming back a second time and others were trying out for multiple roles. Hundreds of people were coming for these 150 roles — it drove me crazy. It must have taken at least a month. It was just a nightmare.

Diane: Had they acted before?

Charles: The South Africans had more experience, I must admit. The Namibians had some stage experience. But they were really wonderful, once I got over that fear, because they didn’t do well in the reading. But once they got on the set it was like, Whoa! They were really into every role, and naturalistic, and you know, we didn’t have a lot of time. It was a low-budget film. But they were just amazing. They had the dedication, the discipline — it wasn’t a problem. They were on the job and doing their thing, overly so, and they didn’t get paid on time…

fear, because they didn’t do well in the reading. But once they got on the set it was like, Whoa! They were really into every role, and naturalistic, and you know, we didn’t have a lot of time. It was a low-budget film. But they were just amazing. They had the dedication, the discipline — it wasn’t a problem. They were on the job and doing their thing, overly so, and they didn’t get paid on time…

Diane: Was your crew international?

Charles: We got the camera, John Demps as D.P., and the focus puller from Los Angeles, and a loader and a line producer from New Jersey, and Ed Santiago as editor and myself from Los Angeles. And everybody else was from Namibia, South Africa, and the African continent — we had people from Zimbabwe. We edited in L.A. and we did the rest of the post-production in South Africa — the mixing, the sound, the color, the print.

Diane: In what ways is the finished film Pan-African?

Diane: In what ways is the finished film Pan-African?

Charles: We have actors from Ghana, Zimbabwe, Zambia, South Africa, people from the States, the diaspora — we brought them all down there to work on the film. So this is actually Pan-Africanism working, in the casting and in the whole idea of the film.

It isn’t done often. You know there’s nationalism and tribalism in the country, and there are job scares and fighting over jobs. But the film itself talks about aid from other African countries supporting everyone fighting in the liberation struggle — so you have the Pan-African theme there. And a lot came out of that. The commitment came because Nujoma and the fighters got aid from these other independent countries, and the idea was to carry on this theme of support from the different countries and peoples of Africa — all of Africa — and in a sense the film celebrates that as well.

over jobs. But the film itself talks about aid from other African countries supporting everyone fighting in the liberation struggle — so you have the Pan-African theme there. And a lot came out of that. The commitment came because Nujoma and the fighters got aid from these other independent countries, and the idea was to carry on this theme of support from the different countries and peoples of Africa — all of Africa — and in a sense the film celebrates that as well.

For me it was a chance not only to play a supportive role but also, concretely, to have a hand in getting a piece of work out that responds to a need. Namibians need to see themselves as members of a Pan-African culture and history. And it’s also important for other African countries — Botswana, Zimbabwe, Angola when gaining independence from Portugal — to see the film and recognize the support that they and their leaders gave to the struggle for liberation throughout Africa.