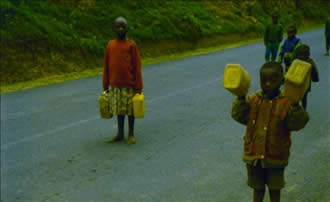

The top prize for narrative filmmaking at the 2007 AFI Fest went to Lee Isaac Chung for his first feature, MUNYURANGABO, about two young men, one Hutu and one Tutsi, on a journey through Rwanda’s haunted countryside. Upon earning a BA in Biology at Yale as a pre-med student, Isaac Chung took a chance on his side-passion for cinema and earned an MFA in Film Studies at the University of Utah in 2005. Once Dept. Chair Kevin Hanson pointed him in the direction of the films to see, he approached cinema “monastically,” viewing ten or more films a week and doing nothing but thinking and working on the craft. After his wife began volunteering at YWAM Rwanda as an art therapist for women survivors still traumatized by the genocide, Isaac Chung joined her there, offering film instruction.

The top prize for narrative filmmaking at the 2007 AFI Fest went to Lee Isaac Chung for his first feature, MUNYURANGABO, about two young men, one Hutu and one Tutsi, on a journey through Rwanda’s haunted countryside. Upon earning a BA in Biology at Yale as a pre-med student, Isaac Chung took a chance on his side-passion for cinema and earned an MFA in Film Studies at the University of Utah in 2005. Once Dept. Chair Kevin Hanson pointed him in the direction of the films to see, he approached cinema “monastically,” viewing ten or more films a week and doing nothing but thinking and working on the craft. After his wife began volunteering at YWAM Rwanda as an art therapist for women survivors still traumatized by the genocide, Isaac Chung joined her there, offering film instruction.

Diane Sippl:So how did Munyurangabo get off the ground?

Isaac Chung:I decided that making a film together with Rwandan students would be the best way for them to learn the art. After researching Rwanda and Rwandan cinema, I wanted to treat the film project very seriously. I invited Samuel Anderson to work on the screenplay with me, and he later joined us in Rwanda during the shoot. Jenny Lund, a fellow film student from Utah I really trusted on the set, came earlier on.

We were in Rwanda for nine weeks; Jenny and I spent most of that time teaching students photography and narrative cinema. We also interviewed people and researched the film, and made all of the necessary preparations for the shoot, which lasted only eleven days at the end of our stay.

cinema. We also interviewed people and researched the film, and made all of the necessary preparations for the shoot, which lasted only eleven days at the end of our stay.

Diane:How did the actors collaborate in writing the screenplay with you and Samuel Anderson?

Isaac:Samuel and I wrote a ten-page treatment for the film in New York, and we filled in the details of the screenplay after we arrived in Rwanda. We cast actors who resembled and added dimension to the characters we developed, and production was a constant set of questions we posed to them about their lives. We wanted to give them a chance to define their characters, and we gave them some freedom to direct the way we would recreate their actual memories. It was an organic process; Sam and I also wrote scenes together in the one-hour car ride to the location every morning.

Diane:Had your actors ever performed before? How did you find them? They were incredibly moving.

Diane:Had your actors ever performed before? How did you find them? They were incredibly moving.

Isaac:We found the two main actors through a program that the Christian base was running for street kids in Kigali. Eric Ndorunkundiye and Jeff Rutagengwa were both living in the slums and met every week with Serieux Kanamugire, a volunteer at the base who was also helping on our shoot. Serieux connected us with the two teens, initially for interviews while we were researching. Their stories were moving and they were best friends in real life, so it soon became clear that we should cast them.

Sangwa’s parents were cast by chance. I was scouting locations, and in a village far from Kigali, we came upon a house that would be perfect for the film. I spent some time with the owners, getting to know them, and I auditioned them for the roles; they were surprisingly good.

The only actor with some experience was Edouard B. Uwayo, who plays the poet. He works as a dramatist for a local radio station and is also well known for his poetry. Edouard was in our filmmaking class, and when I found out that he was a poet, I created an assignment for the class to shoot a series of photographs inspired by a poem; Edouard recited a poem for the class, and I was blown away. I knew that the poem had a place in the film.

poetry. Edouard was in our filmmaking class, and when I found out that he was a poet, I created an assignment for the class to shoot a series of photographs inspired by a poem; Edouard recited a poem for the class, and I was blown away. I knew that the poem had a place in the film.

Diane:You have not only directed and produced Munyurangabo, along with writing it, but you have also shot and edited the film. This suggests not only a total “vision,” but also nearly a total “voice” in making the film. Who inspired you in your filmmaking?

Isaac:I took on so many roles out of necessity. We were shooting quickly, and I knew I could move the production if I was behind the camera. I love both directing and cinematography, but ideally, I would want to separate the roles if time and money allowed it. In any case, I don’t feel that this is a film with a singular voice; given our circumstances, the film grew out of a lot of listening, and it presents the answers to a long interrogation of mine with Rwanda, answers that came from actors, Rwandan friends, and the process of filmmaking itself. I enjoy this method of cinema, the challenge of finding the proper problems and questions.

Diane:You are Korean-American, and yet I felt in viewing your film as though I were watching one by Ousmane Sembene (in the way you value the characters’ work) or Abderrahmane Sissako (in the poetic sensibility of your aural-visual language) or Idrissa Ouedraogo (in the tenderness of your dialogue and actions) or Mahamat-Saleh Haroun (in the father-son relations you develop) or Djibril Diop Mambéty (in your understanding of and compassion for African youths). Do you know the work of these directors? Or is there someone else who brought you closer to your subject matter and approach?

Diane:You are Korean-American, and yet I felt in viewing your film as though I were watching one by Ousmane Sembene (in the way you value the characters’ work) or Abderrahmane Sissako (in the poetic sensibility of your aural-visual language) or Idrissa Ouedraogo (in the tenderness of your dialogue and actions) or Mahamat-Saleh Haroun (in the father-son relations you develop) or Djibril Diop Mambéty (in your understanding of and compassion for African youths). Do you know the work of these directors? Or is there someone else who brought you closer to your subject matter and approach?

Isaac:I’ve seen a few works by Sembene, Sissako, and Ouedraogo, but I haven’t had a chance to watch the others. I didn’t watch any of these until after I returned from Rwanda; I wish that they had more of an audience in the States.

While I’m shooting, cinematic inspiration is subliminal for me, since I usually rely heavily on intuition. There is often not an intellectual commitment to a certain filmmaker or film for the scenes, but I’m certain the influences come through. All of the filmmakers I admire, such as Bresson, Ozu, Hou Hsiao Hsien, seek honesty and accuracy with whatever subject they approach. I was inspired to do that in Rwanda, and I hope that any similarity I have with African filmmakers comes out of a solidarity in our efforts to do the same.

is often not an intellectual commitment to a certain filmmaker or film for the scenes, but I’m certain the influences come through. All of the filmmakers I admire, such as Bresson, Ozu, Hou Hsiao Hsien, seek honesty and accuracy with whatever subject they approach. I was inspired to do that in Rwanda, and I hope that any similarity I have with African filmmakers comes out of a solidarity in our efforts to do the same.

Diane:You use recurring proscenium or internal frames (windows, doors, wells) within your camera frame, and a number of shots with a static camera in a fixed position that allow us to enjoy the beauty of your compositions. These frames seem to serve as thresholds through which the characters might pass (perhaps to another “state” of consciousness or evolution). In another approach entirely, when a youth cries over the loss of his father, your camera pans away from his face up a banana tree, as if to respect the privacy of his feelings. Can you explain these choices in your visual style?

Isaac:I’ve always enjoyed a certain style of framing that reveals dimension and layers of a given space. In Rwanda, particularly, I love the visual look of the mud walls, this emotion that arises from seeing a scene with characters surrounded by earth.

But the added dimension of shots through doorways provides an emotional space as well. This is the way I observe life often, through doorways, in spaces that are not my own. For most of the film, Ngabo is a passive observer, but these observations are important—they shape his ultimate decision as to whether or not he should commit revenge. I decided on most of my shots through this internal journey. I wanted the entire journey to build up to a type of revelation for Ngabo, and I wanted the audience to experience his emotions as well, cinematically.

But the added dimension of shots through doorways provides an emotional space as well. This is the way I observe life often, through doorways, in spaces that are not my own. For most of the film, Ngabo is a passive observer, but these observations are important—they shape his ultimate decision as to whether or not he should commit revenge. I decided on most of my shots through this internal journey. I wanted the entire journey to build up to a type of revelation for Ngabo, and I wanted the audience to experience his emotions as well, cinematically.

This is also what drove a lot of the scenes in which the camera drifts from character to character and sometimes to other objects. I like the subtle way that such a shot can conjure emotion; often they are my emotions as I watch the scene unfold and improvise with the camera along with the actors. For the scene you mention, I shot it a number of ways, but on the final take, when the camera panned and rested on the banana leaves, the wind started blowing on the leaves as the two finished their conversation. It seemed like a spiritual moment for me, a sort of aesthetic order and harmony arising from chance, and it was poignant given the chaos that the two were discussing.

Diane:The use of ambient sound in your film is quite alluring. Did you work on it in any special way?

Isaac:Jenny Lund did our sound on location, and she recorded a lot of natural and ambient sound in different locations and at different times of day. I really owe it to her for having the foresight to provide a good palette of materials for the editing room.

to her for having the foresight to provide a good palette of materials for the editing room.

We shot a lot of the non-talking scenes without any sound, knowing that we would create a soundtrack for those places later. I have always been a fan of the way Robert Bresson approaches his soundtrack, and I admit that I drew a lot from him while editing.

Diane:There is a particular sequence in which you introduce a Ravel piano solo and slow-motion cinematography and then a voice-over. It’s a distinctive break in the aesthetic language of the film and creates an emotional high point. What were you striving for in this sequence?

Isaac:I wanted a distinct separation between the middle section at Sangwa’s home and the last part in which Ngabo travels alone. At Sangwa’s house, it seemed best to me that the audience should be a passive observer and experience the abrupt halt of motion that Ngabo experiences there, this halting of motion that I think nature inflicts upon us if we allow it to. When Ngabo leaves on his own, I wanted the audience perspective and Ngabo’s perspective to merge, along with this idea of motion taking command of the visual language, much in the same way that it signifies the command we take over our own lives. Also, as the film goes deeper into Ngabo’s inner journey, we wanted to introduce more internal elements such as dreams and memories to reveal the character’s reality.

Diane:You incorporate wonderful songs, “spectacles” of dance, and theatrical recitation of poetic speech in your film. These are also breaks in the flow of the narrative. Especially in the latter, the “performer” is shot in a close-up and he directs his gaze straight at the camera (or at the spectator). How did you decide to include these elements?

Isaac:After any large tragedy, there is an inclination to forge a new identity and forget the past. I think part of that impetus is healthy, but there are parts of it that aren’t constructive and allow us to make similar mistakes in the future. In places where I have some familiarity (Asia, Rwanda), the new identity seems to be an economic one in which hope is placed in economic progress. There is an immediate tension between progress and memory, and I believe memory is vital in informing us of our humanity.

Rwanda and many places in Africa find themselves with a certain identity crisis that arises from its tragic past. In fact, the idea of ethnic differences between Hutus and Tutsis was mostly imported by colonialists, and these tribal categories defined Rwandan identity for much of their recent history. Although there is an effort to purge these colonial remnants, the country is trying to enter a global market that’s largely dominated by the culture of the colonizers.

While I’m not suggesting that Rwanda fight against economic prosperity and progress, I am concerned about the way in which Rwandans might think of their past. Although I’m not a big believer in nationalist movements, I do believe in a spiritual quality of traditional arts, the way they preserve memory and identity of the soul, cultural expression that’s rooted in trials and failures, and how they demand that value is placed upon everybody. This is, in effect, what the poet expresses as well, and the other arts were necessary for the themes of the film.

Diane:The ending of your story is a bit of a surprise. Can you explain your purpose?

Isaac:We desired to convey a journey towards reconciliation, and decided that it should be through an image of hope. There didn’t need to be a realistic resolution, but a possible one.

I enjoy cinema that relies more on an emotional journey than upon a plot that builds; for instance, there are films by Hou Hsiao Hsien and Yasujiro Ozu that seem to show only mundane events and then sweep you away at the end. Within the mundane events, there are certain things that are happening below the surface that build upon each other to the point of an ultimate revelation. I pursued this type of storytelling; put another way, I wanted the audience to participate in the film’s resolution by subconsciously drawing upon their own interpretations and experiences.

Diane:You said that the people of the village where you made the film hadn’t seen it yet, and that there is no electricity there. How will they see it?

Isaac:The Rwanda Cinema Center has a portable projection system that we might try to rent. It’s a peculiar situation. We planned on having a big public premiere in Kigali this past summer, but we weren’t able to schedule it while I was there teaching. We’re working on a premiere for June 2008; we would bring the village actors to Kigali, but we also want to do an outdoor, public screening for that particular village.

Diane:Is Munyurangabo the first theatrical feature film made in the language of Rwandans? Is there a film industry there?

Isaac:There are many filmmakers in Rwanda, but it’s difficult to find the means for production. Documentary tends to be less demanding on a financial level. There are narrative productions in the works; our students are even editing their first feature film shot on video. Ultimately, our goal was to make a film for Rwandans and Rwandan audiences, and now, we believe that the best way to accomplish this is to help Rwandans direct their own films. We will continue our involvement there along those lines.