When Jean-Luc Godard wed the ideals of filmmaking to the realities of autobiography and current events, he changed the nature of cinema. Unlike any earlier films, Godard’s work shifts fluidly from fiction to documentary, from criticism to art. The man himself also projects shifting images—cultural hero, fierce loner, shrewd businessman. Hailed by filmmakers as a—if not the—key influence on cinema, Godard has entered the modern canon, a figure as mysterious as he is indispensable.

In Everything Is Cinema, critic Richard Brody has amassed hundreds of interviews to demystify the elusive director and his work. Paying as much attention to Godard’s technical inventions as to the political forces of the postwar world, Brody traces an arc from the director’s early critical writing, through his popular success with Breathless, to the grand vision of his later years. He vividly depicts Godard’s wealthy conservative family, his fluid politics, and his tumultuous dealings with women and fellow New Wave filmmakers.

women and fellow New Wave filmmakers.

Everything Is Cinema confirms Godard’s greatness and shows decisively that his films have left their mark on screens everywhere.

Bijan Tehrani: I think personally that no movement in cinema ever dies or fades out. But there might be a question at this time, so many years after the New Wave, as to what your motivation was behind writing this book, Everything is Cinema: The Working Life of Jean Luc Godard.

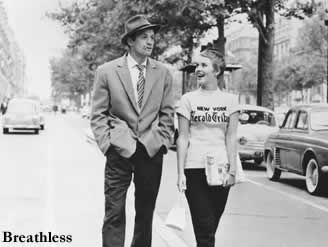

Richard Brody: Godard’s films are what got me interested in the cinema when I was seventeen years old. Pretty much all of my life I have considered Godard and the cinema virtually synonymous. The first film that made me love the movies as something more than a Saturday-night entertainment was Breathless. The more I started watching his films, and as I started reading his writings and discovering the classic Hollywood cinema and world cinema through his writings, I came to understand that this was no coincidence. In other words, of all the filmmakers, Godard is the one who stood at the crossroads of the history of cinema. He was a filmmaker whose work was most nourished by the history of cinema, most dependent on the history of cinema, and that, in effect, brought the history of cinema to its culmination. His work is the culmination of the history of the classical cinema as he absorbed it to the point that he started working. So I think of him as the exemplary figure in the modern cinema, and certainly the most important filmmaker in the last fifty years, the filmmaker whose work exemplifies and embodies the history of cinema more than any other.

BT: I think that Jean-Luc Godard is not only a filmmaker. He has his own philosophy of the world and of life, and has his own way of looking at the world that is not only a personal view but also the view of a philosopher.

BT: I think that Jean-Luc Godard is not only a filmmaker. He has his own philosophy of the world and of life, and has his own way of looking at the world that is not only a personal view but also the view of a philosopher.

RB: I think that is exactly right. I think that in his views he was especially influenced by the philosophy of Jean-Paul Sartre. This comes through very clearly in his work. He made Breathless as the first existentialist film. His work was a very conscious response to Sartre, whose ideas about the cinema were very different than his own. To this day Godard continues to be extremely interested in philosophy, and in his later films he makes very explicit references to several philosophers, including Walter Benjamin and Martin Heidegger. Godard is not merely an important filmmaker but a key thinker of the age.

BT: Yes. He is not only translating a philosophy to a picture, but he is actually putting his thoughts into it. This is what makes him different from other filmmakers who are great translators of philosophy or stories to film.

RB: That’s right. Godard thinks that the cinema has a distinctive place among the art forms, and that the cinema could do something that writing couldn’t. In fact, Godard had started out intending to be a writer. He claimed that he had tried to write novels but didn’t complete them. He thought that the cinema was able to do, artistically and philosophically, what writing couldn’t—namely, unify thought and reality; unify the objective and subjective visions of the world in a way that he thought writing couldn’t. Which is why, although he was very impressed by a film like Hiroshima Mon Amour, he thought that classic Hollywood movies, with their deceptively simple psychology, already go past a quasi-objective film of that sort in their ability to stay on the outside and yet suggest the inside.

writing couldn’t. Which is why, although he was very impressed by a film like Hiroshima Mon Amour, he thought that classic Hollywood movies, with their deceptively simple psychology, already go past a quasi-objective film of that sort in their ability to stay on the outside and yet suggest the inside.

BT: Did he have some sort of fascination with Jean Cocteau also?

RB: He did, as did most of the other young men of the French New Wave. They loved Cocteau’s films. But for Godard I think that those films had a distinctive significance, because here was a writer who was also making films. Godard was heartened by Cocteau’s ability to make films that were both literary and yet distinctively cinematic.

BT: Something that is very interesting in Godard’s work is that he is not very concerned with being original as a filmmaker, but he is more concerned with his own message. RB: That’s right. The originality is in the thought, not in the object. I think it was very hard for Godard to claim originality when he had imbibed thousands of hours of cinema, and was also making films under their influence. Their originality is not necessarily in their direct relationship to the world, but rather in their relationship with the inherited material, which in his case was the cinema, literature, art, and even, as he has often suggested, reality itself. When he films the actor, he didn’t invent the actor; the actor already existed. So, for Godard, from the very beginning there was a second-order aspect to the cinema that was both a blessing and a curse. A blessing because it relieved him of the need to be original, as writers and painters feel they have to be. It was a curse because it put him into a situation of Sartrean bad faith. He was aware of his parasitical relationship with reality, and the moral burden that it placed on him.

RB: That’s right. The originality is in the thought, not in the object. I think it was very hard for Godard to claim originality when he had imbibed thousands of hours of cinema, and was also making films under their influence. Their originality is not necessarily in their direct relationship to the world, but rather in their relationship with the inherited material, which in his case was the cinema, literature, art, and even, as he has often suggested, reality itself. When he films the actor, he didn’t invent the actor; the actor already existed. So, for Godard, from the very beginning there was a second-order aspect to the cinema that was both a blessing and a curse. A blessing because it relieved him of the need to be original, as writers and painters feel they have to be. It was a curse because it put him into a situation of Sartrean bad faith. He was aware of his parasitical relationship with reality, and the moral burden that it placed on him.

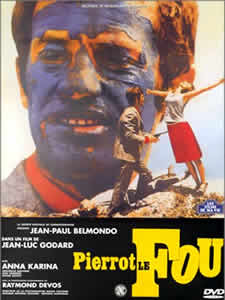

BT: Also, when he was using famous actors for his films, he would find a totally different character from what those actors usually played in other films. For example, Jean-Paul Belmondo is one of them; in Godard’s films he is absolutely a different character.

what those actors usually played in other films. For example, Jean-Paul Belmondo is one of them; in Godard’s films he is absolutely a different character.

RB: Belmondo was more or less discovered by Godard. He was a well-regarded theater actor, but was fundamentally a comic actor. For Godard this wasn’t a problem because there was nothing straightforward about the drama in Breathless. Fundamentally, Breathless is not a naturalistic drama. It is a film of quotations and cartoonish interpolations. Naturalistic dramatic acting never interested him. That’s why quasi-amateurs like Jean Seberg and Anna Karina were always interesting to Godard, and why they fit into his system in a way that they didn’t fit into other people’s films.

BT: There was always a rumor during the New Wave about Andrzej Wajda’s influence. Did that ever come up in your conversations with Godard?

RB: No, it didn’t. I know that Godard considered himself to be influenced by Jean Rouch, the documentary filmmaker, and to a certain extent by Roberto Rossellini, whose Voyage to Italy gave him the idea of possibly filming, with two actors and a car, a drama that had the allure of a Hollywood movie but which didn’t rely on its trappings in any way. The film of Wajda’s that was significant to Godard at one point was Man of Marble, which was twenty years later.

BT: When you are looking at the history of the New Wave, how much of a major player do you think Godard was in the movement?

BT: When you are looking at the history of the New Wave, how much of a major player do you think Godard was in the movement?

RB: On the one hand, his significance in the New Wave is, to a certain extent, self-evident. And yet, the more you look at it, the more peculiar you realize it really was. On the one hand, he was the first of the young New Wave critics to write in Cahiers du Cinéma. He exerted a very strong influence on the others. He acted in a film by Eric Rohmer. He acted in a film by Jacques Rivette in 1950. He was the first to make a professional film, namely his documentary Opération Béton, which he made on 35mm film and sold to the Swiss dam company that he was working for (as a laborer). However, because he was absent from Paris for some time in the early fifties, the critics at Cahiers du Cinéma became famous while he was off the scene. When he came back to Paris he stepped into a movement that was already well under way. Truffaut was the most visible leader of the group, and Chabrol was the first one to make a feature film, but Godard was the first one to make a film that defined the movement in distinction to the other films that were being made at the time. The 400 Blows was a very successful film–it won Truffaut the best director prize at Cannes in 1959–but aesthetically it is not a radical film. Whereas Breathless, which came out in March 1960 and was a domestic and worldwide success, was the film that heralded to the world the fact that the New Wave was not merely a bunch of young directors establishing themselves; it was an aesthetic break from the films that had come before.

1960 and was a domestic and worldwide success, was the film that heralded to the world the fact that the New Wave was not merely a bunch of young directors establishing themselves; it was an aesthetic break from the films that had come before.

BT: How much has Godard influenced American filmmakers?

RB: Certainly in the 1960’s he exerted a very powerful influence. When you read interviews with young film students at the time, such as Francis Coppola, George Lucas, and Brian De Palma, they all said that their ambition was to be the American Godard, to do here what Godard did in France. The influence his later films have had is a much more complicated question. His later films have very rarely been seen, which is part of the problem. Also, they are more explicitly dependent on the history of cinema and on classical learning, which limits their influence to some extent. His later films have exerted much more of an influence in the intellectual, philosophical, artistic realms, rather than in the cinematic realm. Nonetheless, of the New Wave directors, he remains a key reference–early on for American filmmakers, and now for American intellectuals.

BT: Did any of his early issues or events in his life influence his work? I know that he was very saddened by his mother’s death in a motorcycle accident. Did he talk about that? Did you see any effect of that in his work?

RB: I think that there is no filmmaker whose work has been more deeply influenced by his personal life than Godard, and who makes more allusions to his personal life than Godard. Very often those references are coded in a system of allusions that require a certain amount of decoding or deciphering. In Breathless, there is a reference to Lausanne, and at that exact moment  ambulance sirens are heard. Given the fact that the soundtrack to Breathless was dubbed—not recorded on location—the correlation of the two elements was an express choice on Godard’s part. The association of the two, of course, is a suggestion of a terrible accident that took place in Lausanne –namely the death of his mother in a motorcycle accident, but to know this you have to do a little bit of research. Godard has primed the pump for this research with interviews. He used the press as a way of tossing out to readers the lenses through which to watch and interpret his films. The references are certainly there, but they are not necessarily there in forms that are immediately accessible without a little priming on his part.

ambulance sirens are heard. Given the fact that the soundtrack to Breathless was dubbed—not recorded on location—the correlation of the two elements was an express choice on Godard’s part. The association of the two, of course, is a suggestion of a terrible accident that took place in Lausanne –namely the death of his mother in a motorcycle accident, but to know this you have to do a little bit of research. Godard has primed the pump for this research with interviews. He used the press as a way of tossing out to readers the lenses through which to watch and interpret his films. The references are certainly there, but they are not necessarily there in forms that are immediately accessible without a little priming on his part.

BT: In the late sixties and early seventies Godard traveled a lot—going to Canada, the U.S., and Cuba. Why did he go on these trips, and what effect did these have on his work?

RB: In the late sixties Godard started traveling a lot, and started making films in lots of different places, but he had trouble completing the films that he thought of or started working on. He shot a little footage in Cuba but never worked it into a film. At that point in his career he wasn’t quite sure what to do. He was looking for a new way of making films, but couldn’t quite find it. Traveling was a way of looking for something new, and it took him a long time to find what he was looking for.

Traveling was a way of looking for something new, and it took him a long time to find what he was looking for.

BT: Did he ever talk about how he felt about Cuba, or his take on the country?

RB: No, not to me.

BT: When you had your first interview with Godard, in 2000, was that the first time you met him in person?

RB: That’s right. I had seen him in person when he came to New York in 1994 to present JLG/JLG at the Museum of Modern Art, but I didn’t meet him at that point.

BT: How did you find him when you had a chance to sit down and talk? How long were you able to speak with him?

RB: We spoke for about three hours in a formal interview. Then we talked casually in his office. He showed me some work that at the time had not been published, namely The Old Place. We then went out to dinner, and talked over dinner. We were together for about six hours.

BT: How was he with new technology, like the internet? I find that a lot of filmmakers who have been raised in more traditional ways of communication never get a handle on using new technology.

RB: To the best of my knowledge, I don’t think that he is a devoted internet user. He has said in interviews that he doesn’t use the Internet. As far as his work is concerned, he shoots a great deal on video, but he does not edit on digital equipment.  He edits on analog equipment. He explained to me that he doesn’t like working in digital video because the notion of time disappears, because you can jump from one part of your footage to another without any temporal transitions. Whereas with analog or videotape, there is a certain amount of time that it takes to rewind or fast-forward from one place to another. So time remains an element in analog in a way that it doesn’t in digital.

He edits on analog equipment. He explained to me that he doesn’t like working in digital video because the notion of time disappears, because you can jump from one part of your footage to another without any temporal transitions. Whereas with analog or videotape, there is a certain amount of time that it takes to rewind or fast-forward from one place to another. So time remains an element in analog in a way that it doesn’t in digital.

BT: That is very clever, very interesting. In new films it seems to me as if something has been missing, and now it makes sense. What has he been working on lately?

RB: The last completed work is a videotape that he made for an exhibit that he organized in 2006, called “Vrai Faux Passeport”. The last feature film was Notre Musique. In an interview broadcast on ARTE, the French and German television channel, in December, he said he was beginning work on a new film. I believe he said the film would be called “Socialism Would Say Things Like That”.

BT: How was his health when you met with him?

RB: He seemed perfectly well to me. We walked to dinner at basically the same pace. Now he is a man of seventy-seven, but certainly in the television interview last December, he looked to be in good shape.

December, he looked to be in good shape.

BT: What is his influence in France now, and with young people?

RB: I don’t think he has strong personal relationships with large numbers of young filmmakers in France. Every now and then, in an interview, he mentions a film he saw recently that has pleased him. He liked a film by Mathieu Amalric, the actor, and a film by Alain Guiraudie, but I don’t know that he actually has personal relationships with them. As to the effect his work has on them, I think the one lesson a young filmmaker can take from Godard is, “Don’t imitate me. Find your own way.”

BT: I want to tell our readers that I personally found your book not only very interesting and informative, but also very entertaining to read. I could not put it down. I think it is a wonderful book to read for anybody who is in this business, as a filmmaker, film fan or a film student, and I highly recommend it.

RB: Well, thank you. I think that suggests the extent to which Godard’s life and work are extraordinarily and endlessly fascinating.

Richard Brody graduated from Princeton University with a B.A. in Comparative Literature. He worked in various capacities in the film business (including documentary researcher, writer, and producer) and in advertising, before writing and directing, as an independent filmmaker, the feature film “Liability Crisis,” which was released in 1995. He wrote book reviews for the Forward beginning in 1996 and started writing for The New Yorker in 1999; among his publications there are articles about the directors François Truffaut, Jean-Luc Godard, and Samuel Fuller. In 2001, Metropolitan Books/Henry Holt & Co. commissioned him to write a critical biography of Godard based on his profile of the filmmaker that appeared in The New Yorker. Since 2005, he has been the movie listings editor at The New Yorker, where he writes film reviews and a DVD column. Everything Is Cinema: The Working Life of Jean-Luc Godard is his first book. He lives in New York.