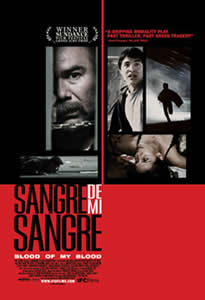

JUAN and PEDRO meet in the back of a tractor-trailer filled with undocumented Mexican immigrants headed for New York City. Pedro shows Juan a sealed letter that his mother, now dead, has given him – an introduction to the father he never knew. He brags to his new friend that his father, DIEGO – who left Mexico for New York many years before – has become a wealthy restaurant owner and will surely rejoice at the arrival of the son he had always wanted. Juan doubts Pedro’s confidence and challenges his expectations. Juan’s father left him when he was four with two things: a switchblade and the scar it made on his chest.

When the truck lands in Brooklyn, Pedro wakes to find himself alone and his belongings, including the letter with his father’s address, stolen. He is cast onto the street and – unable to speak the language – lost in an unknown city. Juan, meanwhile, shows up at Diego’s door with the letter – claiming to be the old man’s long lost son, Pedro. Diego, who is not a wealthy restaurant owner, but a miserly dishwasher who squirrels away every dollar he makes, immediately rejects him. Juan persists, contriving to win his “father’s” favor by maintaining the image of the hardworking, devoted son. Yet rather than working during the day for money, as he claims he is doing, Juan prowls about Diego’s apartment, searching for the hidden stash. In the meantime, Pedro meets MAGDA, Spanish-speaking street-urchin who offers to help but repeatedly exploits his desire to find his father. Pedro must choose whether to abide by his principles or heed Magda’s ruthless logic of the street and “look out for number one.”

doing, Juan prowls about Diego’s apartment, searching for the hidden stash. In the meantime, Pedro meets MAGDA, Spanish-speaking street-urchin who offers to help but repeatedly exploits his desire to find his father. Pedro must choose whether to abide by his principles or heed Magda’s ruthless logic of the street and “look out for number one.”

With every day that Pedro gets closer to finding Diego, Juan gets closer to finding the money. Yet along the way, both boys find something they weren’t looking for… They find something they need.

SANGRE DE MI SANGRE is writer-director Christopher Zalla’s first feature film. Mr. Zalla also wrote a feature film set in a Bolivian Prison, entitled MARCHING POWDER, for Brad Pitt’s Plan B Entertainment. Don Cheadle is attached to star. Mr. Zalla has received an MFA with Honors in directing from Columbia University’s Graduate Film Division, where the faculty awarded him a full Departmental Research Assistant fellowship for merit as a top student. Zalla also served as a teaching assistant at Columbia, where he instructed undergraduates in weekly classes in film history, theory, and craft. Mr. Zalla was born in Kisumu, Kenya and spent much of his youth overseas. He has also worked as a rough carpenter and spent nine summer seasons as a commercial salmon fisherman in Alaska’s Bering Sea. He is fluent in Spanish. Mr. Zalla currently lives in New York City.

Bijan Tehrani: Your film is very powerful. It is about a city, about survival, about everything in life. How did you come up with such an amazing story?  Christopher Zalla: As a filmmaker, one of the hardest things to pinpoint is what exactly your inspiration is. One of my friends that I went to school with was from Argentina, and after he graduated he stayed beyond his student visa, and became undocumented. He started working in restaurants. I would go hang out with him after work, and in so doing would hang out with a lot of the kids who he was working with, who were predominantly Mexican. I got to know these kids and started to hear a similar story from them; which was the story of their plan to come to the States and working for fifteen to twenty years with the aim of then going home and retiring very wealthy. I was struck by the grandiosity and scope of a fifteen to twenty-year plan that a sixteen or seventeen year old could have. But then a sixteen or seventeen year old in another country probably has the maturity of a thirty five year old here. I imagined a character who was at the end of that time period in his life, and who, for one reason or another, wasn’t sending money home, and, because he was undocumented, was forced

Christopher Zalla: As a filmmaker, one of the hardest things to pinpoint is what exactly your inspiration is. One of my friends that I went to school with was from Argentina, and after he graduated he stayed beyond his student visa, and became undocumented. He started working in restaurants. I would go hang out with him after work, and in so doing would hang out with a lot of the kids who he was working with, who were predominantly Mexican. I got to know these kids and started to hear a similar story from them; which was the story of their plan to come to the States and working for fifteen to twenty years with the aim of then going home and retiring very wealthy. I was struck by the grandiosity and scope of a fifteen to twenty-year plan that a sixteen or seventeen year old could have. But then a sixteen or seventeen year old in another country probably has the maturity of a thirty five year old here. I imagined a character who was at the end of that time period in his life, and who, for one reason or another, wasn’t sending money home, and, because he was undocumented, was forced to stash his money. I imagined a miserly son of a bitch for this guy, and a life built on an accumulation of work, and that was it. I thought, “That’s an interesting character, maybe I will put him in the background of a film one day”. Then September 11th happened—I was downtown that day, and it was obviously an overwhelming experience, but on some levels it was an ultimately beautiful experience because everything about New York got stripped down, stripped bare; and I left really wanting to make a movie about the City. During the following week I had this idea of a son coming to claim his birthright from this old man, and wanting to be taken in. At this precise moment I had this idea for the other son, and the whole thing, crystallized. Then there was the process of sitting down for a long time and inventing. Of course these things are largely inspired by your own experiences in life and relationships, which is the case here. That’s the very long answer.

to stash his money. I imagined a miserly son of a bitch for this guy, and a life built on an accumulation of work, and that was it. I thought, “That’s an interesting character, maybe I will put him in the background of a film one day”. Then September 11th happened—I was downtown that day, and it was obviously an overwhelming experience, but on some levels it was an ultimately beautiful experience because everything about New York got stripped down, stripped bare; and I left really wanting to make a movie about the City. During the following week I had this idea of a son coming to claim his birthright from this old man, and wanting to be taken in. At this precise moment I had this idea for the other son, and the whole thing, crystallized. Then there was the process of sitting down for a long time and inventing. Of course these things are largely inspired by your own experiences in life and relationships, which is the case here. That’s the very long answer.

BT: You show a side of New York that almost everyone, even New Yorkers, have not seen. It shows how New York is a totally different country, a world unto its own. Is that true?

CZ: Yes, absolutely. That was one of my really profound experiences on September 11th, looking around me and all of these people from all over the world who were rushing down there to help. New York is absolutely not America; it’s this collection of little societies from around the world that tend to bind together a bit, but that inevitably commingle. To me that is what is so beautiful about the city, that on any given day I can have a Russian day and can go to a Russian bathhouse and have food from the Ukraine. You can pretty much do that with every culture on earth in New York. That’s why I think it is the greatest city on earth, it has all these worlds. However, I think one of the greatest ironies is that so many of us here fall into the routine and conventions of our daily lives, and are not actually aware of all of these worlds. It was one of the things I felt very strongly about this movie, and the aftermath of making it. When I was writing this movie, the whole concept of illegal immigration was not at all in the mainstream discussion—certainly not to the extent that it is today. I wasn’t setting out to make a movie about immigration. I was just making a story within one of these communities, and I wonder – if the immigration debate hadn’t turned into something so big – if the movie would have been allowed to be suggestive of the fact that there are so many more of these stories and worlds that we have not even looked into.

BT: Your own personal experience—you have traveled a lot and done hard work—seems to be reflected in this film. Is that right?

BT: Your own personal experience—you have traveled a lot and done hard work—seems to be reflected in this film. Is that right?

CZ: For sure. When you look back and reflect on things you can see the influence from your life. I did travel extensively as a kid—not by choice. My parents moved around a lot for work, primarily in developing countries. Work in my family, for my father especially, was an absolute. There was no time for any kind of moaning. I was literally growing tomatoes and selling them door to door when I was five years old for 10 cents a bag. I always had to have this drive to work and make money, and I have a profound love/hate relationship with work. My family was all builders, so I learned carpentry. When I was eighteen I went to Alaska on my own and did commercial salmon fishing for nine seasons. The other interesting thing about work in my personal history is that it was the place where men could bond and demonstrate vulnerability. You didn’t talk about relationships or feelings unless you were putting a new roof on a house. Then suddenly, everyone started talking when you were hammering away. It had this interesting duality.

BT: In my experiences, people who have been forced to travel a lot are always looking for a place to settle down, to finally have a home. Is there something inside of you that is reflected in this longing in Juan and Pedro, who are looking for a family and a father?

CZ: Looking for a home. Yes, I’m glad you saw that. That is certainly how I would characterize my own search.

BT: Juan is supposed to be the traditional bad guy of the film, but I found him to be such a loveable character. How did you make him such an endearing character?

CZ: Me too, I adore him. I think it is part of the whole notion of this simple twist of fate and circumstance. Survival really being a product not of fiber and character, or some sort of imposed structure we call morality, but really being a product of circumstance. In terms of Juan, it’s very interesting that you have the reaction you do; which I found among non-American audiences to a much greater degree than American audiences. It was something very specifically that I was trying to explore in the movie;, the way in which we as audiences engage this whole moral paradigm and notion of good and bad. I was constantly trying to shift that paradigm by having someone who we were following do something bad but still win our sympathy, and in contrast the person who is good does something bad. If we keep shifting the paradigm of “good and bad”, we might just realize that the need to classify people as such is useless, and we would abandon it and let these people be fully complicated human beings. It is very interesting to me to put the movie out there in the world and watch the rainbow of reactions that people have to it. There was a beautiful sentiment that came out of Sundance when somebody said, “What you think about this movie and the characters will say more about you than the movie”, which I thought was nice. In the case of Juan, I was absolutely trying to infuse his character with playfulness, likeability. He certainly has a greater survival instinct because he can keep levity about himself in situations.  BT: And he is creative.

BT: And he is creative.

CZ: He is so creative. And that was the thing that I was fundamentally looking for when I was casting. Only one person had that when he came in, which was Armando. He came in reading for the role of Pedro, and when he was auditioning for Pedro he gave this whole post-modern audition that was a commentary on how stupid and naive the character was, and it was very funny because he was mocking his whole character. I told him to come back in and read for Juan, and I started laughing, and then crying, because I saw that he was this character. He is Juan. Armando is Juan. Armando was a street kid, he is now a well-known actor in Mexico, but he is still very much creative, always quick thinking, and a bit of a hustling jokester.

BT: Exactly. I was thinking if he wasn’t a street kid he had the shrewdness to be a filmmaker with his creativity. One thing that is really amazing about the film, and about Mexico, is the great actors they both have. There are actors there now that you don’t see in the world cinema. I’m fed up with the fake acting style in the U.S., and this is such a good example of great acting.

CZ: It is certainly stylistically in tune with what I try to go for. You make that decision partly when you cast, and put your faith in actors who have a certain technique and approach. As the director you create an environment that is so utterly real for the actors that they just stop acting. Ironically, in the movie the most melodramatic scene, which was the closest to acting, was the fight between Diego and Juan. Armando fell to the ground and broke down crying. It took several minutes to get him up and get him back together. He was projecting his own fight with his father onto his scene as Juanr.

and approach. As the director you create an environment that is so utterly real for the actors that they just stop acting. Ironically, in the movie the most melodramatic scene, which was the closest to acting, was the fight between Diego and Juan. Armando fell to the ground and broke down crying. It took several minutes to get him up and get him back together. He was projecting his own fight with his father onto his scene as Juanr.

I completely agree with you in terms of what is going on stylistically with acting. I think what’s happening in Mexico is that there is an appreciation of complexity and subtly, and an interest in portraying someone other than the hero. It is not all about getting the next $25 million movie paycheck; it is about exploring the character. The one thing that was absolutely a common dominator among the actors was a real interest in getting into the different facets of these characters. Jesus Ochoa, who is a master, said to me, “I love the loser! The loser is so interesting!” That very idea is just so un-American. People always ask me, “Why did you go make a movie about Mexicans?” Maybe that was part of it; maybe there is a sensibility there that is much more in line with mine than the sentiments American films carry.

BT: And a lot of film directors in situations like this, and in movies like this, they cast ordinary people playing themselves. That is good and interesting, and makes things believable, but that’s it. They don’t go beyond that. They don’t introduce something that is a lot more important, which is what is artistic about movies.

BT: And a lot of film directors in situations like this, and in movies like this, they cast ordinary people playing themselves. That is good and interesting, and makes things believable, but that’s it. They don’t go beyond that. They don’t introduce something that is a lot more important, which is what is artistic about movies.

CZ: I find that they don’t have the acting chops, frankly. You need at some point to have the acting come in. The way I would balance that—because I do very much like that realism—is that I would put them in an environment that was filled with real people. In the scene when they are going to find work on the work corner, we went to a work corner that morning and hired a bunch of people. In the kitchen scene the guys in the background we found in actual kitchens, and several of them worked in that kitchen. These guys would just get to work, and then the actors would show up and just plug in. We shot 16 minutes of film and just let them play around and have fun, both the actors and workers. It was this way to create a sense of being in a real space, and a sense of authenticity.

BT: One other performance in the film that is absolutely amazing is Jesus as Diego. It reminds me of the first time I saw Orson Wells.

CZ: That’s funny because I had three movies that influenced me…well probably more than that, maybe four…and “Touch of Evil” is one of them. It is a film about borders and boundaries, and crossing them, and doing that on a moral and physical and geographic level. And also visually, stylistically it’s still ahead of its time.

borders and boundaries, and crossing them, and doing that on a moral and physical and geographic level. And also visually, stylistically it’s still ahead of its time.

BT: Another amazing piece of acting in this film was by Paola Mendoza. I have always been looking to see who could be the next Guilietta Masina, and she is so good at playing the part of Magda and, bringing this very sensitive character out.

CZ: Yes. Just to step back, Jesus’ performance is phenomenal. If one thing could happen from this film it would be for the world to start banging the drum and say, “Hey everybody, go look at this guy’s performance.” As far as Paola goes, that was a very tough search. We looked at hundreds of girls for that role. On some levels I think it is the weakest written role in the movie, which is my fault. It is also because the character is the connective tissue between the stories, and therefore bears that functional responsibility, which affects the character. What was so interesting about Paola is that she is very intelligent, and she is an operator—there is always an agenda working. She has also had a hard knock life, and was on the streets as a kid. She was uprooted from Columbia as a three year old and came to the States. Her father promptly abandoned the family when they got to the States, her mother had  to work in a Jack in the Box and learn English, and Paola had to live in that environment. I actually did the most rehearsal work with her, because I think both of us had to find the character a bit. But the work that she turned up with – the utter emotional complexity that she brought to a character that is almost by definition fraught with pitfalls-, was outstanding. Just a beautiful, complicated humanity. I’m excited to watch her career flourish.

to work in a Jack in the Box and learn English, and Paola had to live in that environment. I actually did the most rehearsal work with her, because I think both of us had to find the character a bit. But the work that she turned up with – the utter emotional complexity that she brought to a character that is almost by definition fraught with pitfalls-, was outstanding. Just a beautiful, complicated humanity. I’m excited to watch her career flourish.

BT: Finally, after making such a beautiful film, it is hard to make the next one. What is your next project?

CZ: After making a passion project and going into such deep dept, it is very hard to do that again. You have to make a living at some point, I guess. I am writing a script of my own, and have a few other projects I am excited about. The sad truth is that in making a small movie; you don’t just make the movie and move on. It is a commitment years later. Even now as we are releasing next week, I am spending all day on the computer, or putting postcards on cafes, just trying to put the movie on peoples’ radars. We have been extra challenged because the title of the movie was changed. All the people who were aware that it won at Sundance may not be now, so it has been a real challenge.