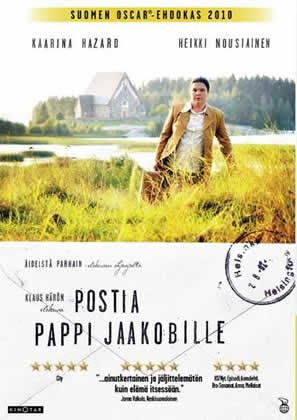

Letters to Father Jacob is story of Leila, a life sentence prisoner who has just been pardoned. When she is released from prison, she is offered a job at a secluded rectory and she moves there against her will. Leila is used to taking care only of herself, so trouble is to be expected when she starts working as the personal assistant for Jacob, the blind priest living in the rectory. Every day the mail man brings letters from people asking for help from Father Jacob. Answering the letters is Jacob’s life mission, while Leila thinks it’s pointless.Leila has already decided to leave the rectory when the letters suddenly stop coming. Jacob’s life is shaken to its foundation. Two completely different lives are intertwined unexpectedly, and the roles of the helper and the one being helped are turned upside down.

Finnish director/writer Klaus Haro is an award-winning filmmaker, best known for “Mother of Mine” (Audience Award/Palm Springs International Film Festival; Crystal Bear/Cairo International Film Festival); “Elina: As if I Didn’t Exist” (Crystal Bear/Berlin International Film Festival) as well as “The New Man.” In total, Haro’s films have won more than 60 prizes in festivals around the world, and in 2004 he was awarded the Ingmar Bergman Award, the winner of which is chosen by Bergman himself.

In November 2009 alone, true to his award-winning history, Haro’s “Letters to Father Jacob” has won Best Film and Best Screenplay at the Cairo International Film Festival; Audience Award at  Lübeck Nordic Film Days; Main Award at Mannheim-Heidelberg International Film Festival and Best Film and Best Screenwriter at Tallinn Black Nights Film Festival.

Lübeck Nordic Film Days; Main Award at Mannheim-Heidelberg International Film Festival and Best Film and Best Screenwriter at Tallinn Black Nights Film Festival.

Bijan Tehrani: In your films, (that I had the opportunity to see them at the Scandinavian Film Festival LA), there are several repeating themes. In the movie Elina As if I Wasn’t There, we observe a lonely character looking for communication, in Mother of Mine, Eero is also a lonely figure looking for connection, and in A New Man, Gertrude is in a similar situation. Letters to Father Jacob provides a tale in which both main characters exhibit loneliness and a quest for communication and inner peace. Is this something that you intentionally do in your films?

Klaus Haro: First of all, just let me say how surprised I am that you have seen my films because I come from a film culture community which is very small, so anytime that somebody outside of the community says that they have seen all of my films, I’m totally surprised: so you have just taken me by total surprise and I am humbled by this. To answer your question, it is not a decision that I make, but I notice it when choosing films to make. I can look back in retrospect and find that there are things that my films have in common, but it is not planned. It would be hard for me to analyze myself, but as you say, this is a film about people seeking connection and people finding friendship where it is not to be expected. This film is very much about finding friends and finding people who stand by you when you don’t expect it and when you need it the most. Letters to Father Jacob is about two very lonely and very different people; what attracted me the most is that I could very well feel for the both of the characters: I am a Christian but I have not always been that way, so I can very well see that world from the inside and also from the outside: How religion can totally absorbed you and how your longing for something pure and true is a part of you. Externally, looking at people praying and reading the bible may seem silly and revolting. So I can look at things from both sides and see how much of an enchanting and wonderful idea it would be to be there with Leila. I was captivated by that cinematic idea and I could really see what Leila experiences here. I wanted to desperately see what was going to happen here and when I finished on page seventy or eighty of the script, I thought, “Why didn’t I think of this?” There were many themes in the script that were very close to me: about looking for redemption, finding friends where you don’t expect it. At the same time the script had great cinematic context, where characters were wonderfully drawn, and I loved the simplicity it in all. I wanted to start working on the script and therefore I called the writer and offered to do some rewrites. She was a small time writer and so she was eager to get someone to work on her script.

BT: Can you pause there, Klaus, and tell us the story of how you came across this script?

BT: Can you pause there, Klaus, and tell us the story of how you came across this script?

KH: The whole thing was a big surprise for both the writer and I. Two years ago I was at home and I had the flu. I was feeling useless walking from room to room, not getting anything done, and then this script comes in the mail. In Finland, we do not have agents because the place is relatively small, so I know most of the script writers by name. If I receive a script from someone that I don’t know, I cannot take the time to read it because I am usually working on something else. Since I had the flu, I decided to just look at a few pages and I was instantly caught. So I called this person without even knowing it I was going to speak to a man or a woman; there was no background or history of this person, nothing, in front page it just said J. Makkonen. I thought, how rude to send me a script and imagine that I am going to read it, but I wanted to call and explain my interest. I soon found out that my writer was in fact a lady, and it turned out that she was a film student in her forties who worked as a social worker, but she had taken time off from her job to go to film school. Her teacher had encouraged her to send her script and she sent it to me only because her teacher told her too. So when I called her, she thought that it was a joke and it was one of her student friends calling her. We finally met and I explained to her that I liked the script very much and that she had created wonderful characters and a great cinematic story. She agreed to allow rewrites and I wanted to be really nice and fair to her because she was a newcomer and I did not want to offend her, so I sent her every rewrite. She didn’t come to the shooting because she did not want to be in the way, and she did not come to the premiere because she did not want to be in the limelight. She wrote this story out of her own necessity to write, and she was very happy to have the experience of watching the story become a film. She viewed the project as a gift. This was a gift; something that she had to write became something that I had to film.

became something that I had to film.

BT: In the film there are times that you feel father Jacob and Leila are switching places. You have this woman who does not believe in what Father Jacob is doing, answering letters of people asking for prayers, and then when he loses faith, she is the one that brings him back to God. Every time that a character changes their beliefs in a film, it is difficult to make it believable for your audience; how did you mange to pull it off so effectively in this film?

KH: I don’t know how, I know that I was very fortunate. One of the reasons that I picked this script, besides from the great writing, would be that on page twenty of the script I was already imagining these two actors in the roles. These are two actors that I wanted to work with for a very long time, and I have to say that they contributed a lot to the believability; they pointed out many things that helped us make the film more convincing. I can only point to them and say that they did some fantastic work. They were really trying to step into their characters. What this film is about, and what really attracted me to the film originally, is that it’s very much about human frailty and who we are when we are at our weakest. Father Jacob has to leave his life and he realizes that he is loved whether or not he is successful. This is a theme that I live with very closely and it very much has to do with how I view life. When we were shooting the film more than a year ago, nobody was talking about an economical crisis or recession of any sort. When the film opened in April of 2009, people all over had lost their jobs and their lives had changed, and this really hit a nerve here. We did not expect a big audience, but here in Finland we had great numbers especially for a film this quiet and still. So this is what this film is about for me: who you are when you are your weakest and do human beings have values within them.

BT: As far as working with the actors, where they allowed to improvise or were they instructed to follow the script.

BT: As far as working with the actors, where they allowed to improvise or were they instructed to follow the script.

KH: It was not direct improvisation; it was more like flow reading. They were pointing out things to me and we would then find the best solution for how to handle it. So we weren’t improvising that much on the set. In a film, the script is so important because you have to have a solid foundation. You really do your best with writing, and you really try to have a solid script. We don’t change writing that much, we try not to, because we believe that the effort that is invested in a script is important and we want to base the film on this and grow from that. But in this case, I would say we had really thorough readings and tried to connect to the film. I think that one day, Leila was really blunt about an issue of Finnish dialect. That led her to loosen up a bit throughout the script and have that sort of blunt attitude of not caring and this led to a lot of humor. When Father Jacob put on those lenses which did not allow you to see at all, he really encompassed the character; so I believe that, eventually, everything will fall into place.

BT: How did you come up with the visual style of the film?

KH: Pictures come very naturally to me. My approach when I was in film school in the nineties and when I became interested in cinema was through cinematography. When you see Citizen Kane and just marvel at the camera work, or when you see films by Akira Kurosawa, John Ford, or David Lean you realize that filmmaking is about telling stories through pictures. I am pleased that audiences notice the visuals, since I’ve always had a natural interest in that. But I’ve had to learn about acting, so when people praise the performances I’m very glad and surprised as well. There are many great actors in this country and in your country that I would love to work with, but what I usually do is that I try to draw from them. But cinematography has been very easy for me and working with the cinematographer has been a great joy and it is always a wonderful experience. The lighting and the colors come together easily sometimes, but choosing the pictures themselves is not always so romantic. I think Akira Kurosaw had a quote when he was asked about a particular framing shot I his film Ran, he responded that: “On the left side we had the airport, and on the right side we had the sewing factory.” You have a plan and you have an idea on how the film will look. When I read a script and I feel that there is a real them that I can get excited about, I am eager to make the choice to make that film. When talking about Letters to Father Jacob, we had an idea about this house that would look older and represent its inhabitant; we needed the house to be one with him, in a way. We  also had to create a place for these characters to feel comfortable in. These were the sort of things that came to me early in the script; we had a very short amount of time to do the movie, so from the start we decided to go for simplicity. We wanted to just set the camera and allow the actors to move around within the frame. We used cinemascope, which really allows separating characters on the opposite end of the frame. We always used the simple path; we had many instances where we did scenes in one set-up. When you have a lot of actors, it can become complicated, but we had a very small crew who was very loyal and everyone really contributed to this. When I look back at those summer weeks, it felt like a vacation.

also had to create a place for these characters to feel comfortable in. These were the sort of things that came to me early in the script; we had a very short amount of time to do the movie, so from the start we decided to go for simplicity. We wanted to just set the camera and allow the actors to move around within the frame. We used cinemascope, which really allows separating characters on the opposite end of the frame. We always used the simple path; we had many instances where we did scenes in one set-up. When you have a lot of actors, it can become complicated, but we had a very small crew who was very loyal and everyone really contributed to this. When I look back at those summer weeks, it felt like a vacation.

BT: I know that you are coming to Los Angeles soon, and we have an event that is very dear to us, the Scandinavian Film Festival. Will you be attending this festival?

KH: Yes, of course! I will definitely be there for the Los Angeles premiere of the Film.

BT: Your film has been chosen to represent Finland at this year’s Academy Awards. How do you feel about the nomination and its chances of winning?

KH: Like I said, I was so surprised when you said that you had seen my films. When I was a film-freak teenager in my town in Finland, I wanted to see films from Scorsese and Coppola, and even the old masters like George Stevenson and John Ford; nobody, absolutely nobody wanted to see those films when we went to go rent movies. Since those days, I had a feeling that I wanted to see the movies that nobody else wanted to see, so why would anybody be interested in the films that I create? I know that two of my earlier films have been nominated, so it seems that when you expect something to happen, it won’t; but when you don’t expect it, it will. This was not expected, so I am just honored. This screenplay just found me. It was gift for me, and when life gives you gifts you just take them, so we’ll see what happens.

BT: Thanks! It was great talking to you, and best of luck.