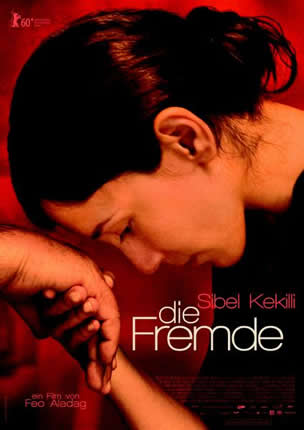

When We Leave, Germany’s Oscar Selection for 2011, is the story of German-born Umay who flees from her oppressive marriage in Istanbul, taking her young son Cem with her. She hopes to find a better life with her family in Berlin, but her unexpected arrival creates intense conflict. Her family is trapped in their conventions. They are torn between their love for her and the traditional values of their community. Ultimately, they decide to return Cem to his father in Turkey. To keep her son, Umay is forced to move again. She finds the inner strength to build a new life for herself and Cem, but her need for her family’s love drives her to a series of ill-fated attempts at reconciliation. What Umay doesn’t realize is just how deep the wounds are and how dangerous her struggle for self-determination has become…

When We Leave, Germany’s Oscar Selection for 2011, is the story of German-born Umay who flees from her oppressive marriage in Istanbul, taking her young son Cem with her. She hopes to find a better life with her family in Berlin, but her unexpected arrival creates intense conflict. Her family is trapped in their conventions. They are torn between their love for her and the traditional values of their community. Ultimately, they decide to return Cem to his father in Turkey. To keep her son, Umay is forced to move again. She finds the inner strength to build a new life for herself and Cem, but her need for her family’s love drives her to a series of ill-fated attempts at reconciliation. What Umay doesn’t realize is just how deep the wounds are and how dangerous her struggle for self-determination has become…

When We Leave is Feo Aladag’s debut as a producer, scriptwriter and director. Born in 1972 in Vienna, Feo Aladag studied acting and psychology and communication science (PhD) in Vienna and London. In 1991, Adalag began working as a freelance editor for daily newspapers in Austria, writing mainly about film and television. She progressed into working on numerous videos and  commercials and has also written several scripts for television, some of which were brought to life with director Züli Aladag. Following her Directorial Masters classes at the European Film Academy with directors like Michael Radford and Mike Figgis, she began studying directing at the German Film & TV Academy in Berlin in 2004. While working as a director of some commercials, Feo stayed very close to her acting career as well. Examples of her work as an actress include series such as Tatort and TV movies in Germany and the U.K. She also played roles in feature films like Lucy (2005), directed by Henner Winkler, and MEINE SCHÖNE BESCHERUNG (2007), directed by Vanessa Jopp.

commercials and has also written several scripts for television, some of which were brought to life with director Züli Aladag. Following her Directorial Masters classes at the European Film Academy with directors like Michael Radford and Mike Figgis, she began studying directing at the German Film & TV Academy in Berlin in 2004. While working as a director of some commercials, Feo stayed very close to her acting career as well. Examples of her work as an actress include series such as Tatort and TV movies in Germany and the U.K. She also played roles in feature films like Lucy (2005), directed by Henner Winkler, and MEINE SCHÖNE BESCHERUNG (2007), directed by Vanessa Jopp.

In 2005 Feo Aladag and Züli Aladag jointly founded the film production company Independent Artists Filmproduktion, based in Berlin. When We Leave is Independent Artists Filmproduktion’s first theatrical feature film! The following is CWB’s interview with Feo Aladag.

Bijan Tehrani: What originally motivated you to make When We Leave?

Feo Aladag: Well, my principle interest is in human relationships, as a metaphor for everything else in life: politics, morality, social issues and a lot more. I wanted to tell a story about the importance of grasping each and every opportunity in reaching out to one another and understanding that our similarities are much more important than our differences and that we should not ever allow principles and convictions to stand in the way of reaching out to those we love. I wanted to raise questions and tell a story about the incredible tragedy of missed opportunities in reaching out to one another. What is it that makes us define our relationships by our differences and makes us chain our love to some sort of condition instead of letting our similarities be stronger than what forces us apart? So it is not primarily a Germanâ€Turkish immigrant story, but a global subject that affects us all today. It’s about overcoming intolerance. When We Leave tells a young woman story, who tries to lead a life of self-determination, who is struggling to develop her own identity. At the same time she has a deep respect for the differing identity her family is cultivating. She is deeply convinced that her love is stronger than the differences and there is a glimmer of hope in my film that she is right despite the occurring drama. The source of hope is love –  her love of her family, her family’s love of her.

her love of her family, her family’s love of her.

BT: And how did you come up with the idea of When We Leave?

FA: Seven years ago my attention was drawn to a series of honor killings being committed in Germany and in many other parts of the world, women who had simply tried to free themselves from family and social restrictions and lead a life of self-determination without losing the love and loyalty of their family. In connection with Amnesty International’s “Violence against Women” campaign, for whom I had directed several social interest spots at the time, I also spent a long time researching related subjects. When my work there was finished, there was something still within me that I couldn’t Ì let go of. I tried to figure out what it was and one key image in particular kept popping into my head: the image of an extended hand, a hand that enables us to bridge every gap that separates us. In a way that was my central abstract idea. I did research for almost two years before I started writing the script. From living in women’s shelter houses, to talking to victims of honor crimes and their families, to working together with experts on this issue, to reading and educating myself on everything there is regarding those mechanisms I did every kind of research you have to do in order to explore the world that I was going to write about. Most importantly I was listening to people who were generous enough to share their very personal and intimate experiences with those dynamics and intimate emotions for which I will forever be grateful. I took the emotions I was trying to convey and set them in a world I wanted to explore and tried to analyze them to see how the trappings of a society affected these emotions. In the attempt to understand the complex mechanisms that are unleashed within the family structure in the case of honor crimes, which can escalate to murder. The deeper I delved into the material, the more strongly I was gripped by the urge to tell a story that dealt with the fate of a young woman who tries to lead a life of selfâ€determination and, at the same time, maintain the solidarity and love of her family. When I started writing, I knew that I wanted to have complete creative independence. So I started my own production company while I was writing, and when I had raised the budget I knew I could start out and direct my first film true to my own vision.

world I wanted to explore and tried to analyze them to see how the trappings of a society affected these emotions. In the attempt to understand the complex mechanisms that are unleashed within the family structure in the case of honor crimes, which can escalate to murder. The deeper I delved into the material, the more strongly I was gripped by the urge to tell a story that dealt with the fate of a young woman who tries to lead a life of selfâ€determination and, at the same time, maintain the solidarity and love of her family. When I started writing, I knew that I wanted to have complete creative independence. So I started my own production company while I was writing, and when I had raised the budget I knew I could start out and direct my first film true to my own vision.

BT: How much of the events in the film are based on real events?

FA: It’s pretty much the essence of many different real life cases. It’s a combination of various cases. You take from one real life case and take different bits and parts and transform them into something new. What struck me while I did the research was that if you take the psychological and the dramaturgical structure of these chains-of-events, they seem very parallel and they often follow very similar patterns and I was struck by that. I realized that this ambivalence between the need for a life of independence and self-determination and the need to be accepted and loved by your family were the base of those mechanisms. For instance, the fact that women who are victims in these cases always tend to go back to the family—they tend to always go back and try again. There is an ambivalence of going away from the structure and going back to structure, so there are strong similarities with all of the stories I researched. And as always in writing you sometimes take more from some real life stories than from others. I spent a lot of time in courts and I sat completely through two of the cases that were being widely covered by the media and it was very interesting observe.

BT: How has the reaction of the Turkish community to this film in Germany?

FA: Before the film came out in theaters, it premiered at the Berlin International Film Festival. And the day before the opening night, Turkey was actually the first country to buy the film for their territory. A month later, when we released it in Germany, I was secure in the fact that there would be a large Turkish audience at the premiere. There are more 2.7 million people of Turkish descent living in Germany; whether they are first, second or third generation, they are a part of this society and they are a part of this richness of bringing in another culture. The film definitely helped in the sense that people took a stand and said, “This is our attitude and we have to do anything we can to go against these ideas and to reach out to the older generation.” Obviously, there is also a small minority where those mechanisms still apply because those people would not go to the cinema, so it was our job to bring the film to them. The feedback from the people who would not usually go to a film was a very emotional one. Some of our audiences shared, in front of others, many personal stories. For example, an older man stood up and said that he very much understood the father in the film and felt very close to him but that he also feels so much empathy for the daughter in the story. He wanted to thank me because the film really made him think and question these ideas. So it was quite amazing how people reacted to the film; sometimes people would hug me and say thank you for telling my story. Even after all of my research I was surprised at  how many women felt that this film was telling their story. I always thought that people would react emotionally to this film but I did not know that it would be to this extent. I have been privileged to present WHEN WE LEAVE in 28 countries, on 5 continents, it´s being screened at 52 international film festivals now since its release in march 2010. The audience reactions across all cultural, ethnical and lingual borders have shown an overwhelming support for the films key messages to overcome intolerance. Audiences have shared their stories and their emotions with me in a way that leaves me blessed as a person. I took the film to Pakistan two weeks ago and I was curious of what the reaction would be there because Pakistan— according to the UN—has the most honor killings worldwide. What I found was the kindest and most wonderful population of people and they really embraced the film. Of course, there was one person who stood up and really wanted to pick a fight with me, and the audience stood up against him and basically told him to go home with his extremist attitude.

how many women felt that this film was telling their story. I always thought that people would react emotionally to this film but I did not know that it would be to this extent. I have been privileged to present WHEN WE LEAVE in 28 countries, on 5 continents, it´s being screened at 52 international film festivals now since its release in march 2010. The audience reactions across all cultural, ethnical and lingual borders have shown an overwhelming support for the films key messages to overcome intolerance. Audiences have shared their stories and their emotions with me in a way that leaves me blessed as a person. I took the film to Pakistan two weeks ago and I was curious of what the reaction would be there because Pakistan— according to the UN—has the most honor killings worldwide. What I found was the kindest and most wonderful population of people and they really embraced the film. Of course, there was one person who stood up and really wanted to pick a fight with me, and the audience stood up against him and basically told him to go home with his extremist attitude.

At the heart of the drama lies, as a glimmer of hope, the missed opportunity for mutual reconciliation. I believe in cinema it is much stronger to give the audience a feeling for where a solution, a chance for reconciliation could have been, rather than lecturing an audience on those solution on an 1:1 level. Raising questions, instead of giving instant solutions to conflict is a key potential of storytelling I believe. When We Leave a drama about the universal wish to be loved by our family for who we are – rather than for the way we choose to live. It is a story in which nobody is condemned but I wanted it to make the compulsions and conflicts as well as the tragedy of all the characters emotionally comprehensible. My intention was to create empathy for all of the  characters trapped in this conflict and to humanize them – beyond the prejudices of the media and ethnic and cultural blame. I truly believe there must be a sustained effort to listen and learn from each other, to respect one another, and to seek common ground. The prerequisite for this is belief, not in an explicitly religious sense, but in the sense of the hand extended between people, the belief that a harmonious coexistence is possible if we, in the name of empathy, grow beyond the shadows of our principles and convictions. I guess this theme is quite universal, as it affects all of us, whether it is people who love one another or people who share a society, a country or a planet and are therefore a community. The important thing, it seems to me, is that we believe in the possibilities of one another. This belief often requires courage, especially in the microcosms of the family as the basis for coâ€operation in the socioâ€cultural context. We live in a multicultural society, which can no longer simply promote consensus but must find new ways to get around arising divergence, and that will only happen with ongoing dialogue and allowing ourselves to be being guided by our similarities rather than by our differences.

characters trapped in this conflict and to humanize them – beyond the prejudices of the media and ethnic and cultural blame. I truly believe there must be a sustained effort to listen and learn from each other, to respect one another, and to seek common ground. The prerequisite for this is belief, not in an explicitly religious sense, but in the sense of the hand extended between people, the belief that a harmonious coexistence is possible if we, in the name of empathy, grow beyond the shadows of our principles and convictions. I guess this theme is quite universal, as it affects all of us, whether it is people who love one another or people who share a society, a country or a planet and are therefore a community. The important thing, it seems to me, is that we believe in the possibilities of one another. This belief often requires courage, especially in the microcosms of the family as the basis for coâ€operation in the socioâ€cultural context. We live in a multicultural society, which can no longer simply promote consensus but must find new ways to get around arising divergence, and that will only happen with ongoing dialogue and allowing ourselves to be being guided by our similarities rather than by our differences.

BT: How did you go about casting the film?

FA: I wanted to keep it authentic in every aspect, also regarding language and therefore I wanted the actors that I worked with to be from Turkish-origin. For the parental roles, I wanted the  parents to actually be from Turkey and I found some actors that I admire greatly and really wanted to work with. I met Settar Tanriögen who plays the father and he said that he really wanted to play this part; he had a teenage daughter and said that if he did not leave his daughter with important roles like these, then what to leave her out this profession? I had a very heterogeneous ensemble in the sense that they all brought very different acting backgrounds – or non at all – to the table. I had street cast the brothers and sisters and the kid over a period of one and a half years and conducted a workshop with them based on a much orchestrated script.

parents to actually be from Turkey and I found some actors that I admire greatly and really wanted to work with. I met Settar Tanriögen who plays the father and he said that he really wanted to play this part; he had a teenage daughter and said that if he did not leave his daughter with important roles like these, then what to leave her out this profession? I had a very heterogeneous ensemble in the sense that they all brought very different acting backgrounds – or non at all – to the table. I had street cast the brothers and sisters and the kid over a period of one and a half years and conducted a workshop with them based on a much orchestrated script.

With all the actors it was important to me to create an atmosphere of trust by going through an intense rehearsal process in order to work on the way I wanted to shoot the film – to work on my set-ups, the optics and the visual language. While I did not alter the script or the dialog while rehearsing, but worked extremely close to script while filming, I believe establishing relationships between all actors and working with them on their background for playing a family is just as important to me during rehearsals as it was to create an atmosphere of trust between all of us and make the cast feel safe and protected in order to be able to reveal their most vulnerable sides and we can create moments of truth.

BT: Do you have any new projects lined up?

FA: Yes, some very interesting ones and I´m burning to work on them and get going. But I would to love to speak to you about them in detail when the time is ready.

When We Leave premiers in LA on Oct. 20 as part of German Currents