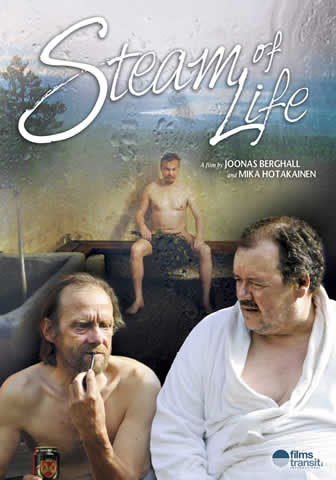

Joonas Berghäll & Mika Hotakainen’s “Steam Of Life” is a beautiful freak, the sort of film Robert Koehler of Cinemascope dubbed an “in- between-film.” In this case it’s a doc that feels like a narrative. (Reviewed in “Best Films Of 2010” and “The 12th Scandinavian Film Festival-Scandinavian Oscar Submissions.”)

Joonas Berghäll & Mika Hotakainen’s “Steam Of Life” is a beautiful freak, the sort of film Robert Koehler of Cinemascope dubbed an “in- between-film.” In this case it’s a doc that feels like a narrative. (Reviewed in “Best Films Of 2010” and “The 12th Scandinavian Film Festival-Scandinavian Oscar Submissions.”)

Saunas have always been a spiritual place for Finns. In Finland, before electricity, saunas were used for birthing and for washing the dead. Saunas offer a womb like refuge to the cold, a place where class distinctions are washed away.

“Bathing in a sauna performs for a Finn the same function as seeing a therapist might for a middle-class man in America.” In 2005, Joonas Berghäll was depressed, and going to a sauna was the one thing that made him feel better. Stories he heard at the oldest public sauna in Finland inspired him to make the film.

Joonas never met his father. For him, the film was a way to “find a ‘Finnish man,’ my father, and also myself.”

Shooting was tricky. Working in rooms that were 200 degrees Fahrenheit and humid, the crew, stripped naked, squeezed into the sauna with the subjects. To keep the lens from getting blurred, they slowly warmed the old 16 mm camera to the sauna’s temperature before shooting on their s16 stock.

The God of Comedy smiled on us as I interviewed Mika Hotakainen, one of the two directors of “Steam Of Life.” The only quiet place we could find, at the annual holiday party at the Finnish Consuls house in LA, was the sauna.

Robin Menken: How did you two begin working together?

Mika Hotakainen: We studied one year in the same class, the basics of audiovisual area and something clicked.

RM: How old were you?

MH: I was 21 and he almost was the same age.

RM: And now?

MH: I’m turning 33.

RM: So you’ve really working since you met in this class?

MH: We made some music video stuff and short fictions. We separated. We went to different film schools. For a couple of years we didn’t do anything. We got an idea for a documentary, “Freedom To Serve.” it was my final work for school, professionally funded, about the Finnish military system. There’s a draft army, every man has to go, or you have an option to go to civil service, or you go to jail.

RM: How did this topic of the male psyche, the feelings of men come up? We had a movement here; a response to the Woman’s movement of the70s’ called Iron John (based on the work of poet Robert Bly.) Men would go to the woods together and out their feelings. It seems like this movie is that for Finland.

MH: In the last 10-15 year, there were a lot of films dealing with female feelings, practically nothing about men. We felt it would be a good time to update the image of Finnish men. It still seemed to be that old fashioned image of a man who didn’t speak, a tough image, somehow, i didn’t relate to that image myself. Time to make a film where we can actually see the emotion of Finnish men.

RM: What’s interesting to me, too it’s a documentary that feels emotionally like a narrative film, that brings a lot of surprising emotion, and it looks like fine art photography with a lot of irony. These beautiful static framings that you do which remind me of Wes Anderson, although he creates and art directs them, inside these little tableau boxes, these prosceniums that are perfectly framed, come these incredibly emotional conversations. Most of the humor comes from the visuals, except for things like the Santa scene. There are very funny scenes in the movie. Did you know when you started that there would be this mixture of humor and grieving? Did you have a sense of what the tone would be? How did that affect the way you shot those frames, those visuals?

(Originally they were going to shoot in the oldest Finnish Sauna where Joonas first met some of the men. During the script writing process, they realized they needed more locations, more diversity, and different kinds of Finns.)

MH: It all came together in the writing process. One financier who’d just got a job at one institution in Finland, which put money in the film

RM: called? MH: The Abek institute, it’s hard to translate, let me think. It’s like Enhancement Center for for Audio Visual Arts…anyway, he wanted to see what kind of a script it was, because a doc script is very different from a narrative feature film, of course. He met Joonas, came to tell him “Congratulations, that script is exactly like the film. “We thought about it. We needed to have these kinds of breaks in the story. It’s a ritual going into the sauna. You have a break, you go outside, get some fresh air.

MH: The Abek institute, it’s hard to translate, let me think. It’s like Enhancement Center for for Audio Visual Arts…anyway, he wanted to see what kind of a script it was, because a doc script is very different from a narrative feature film, of course. He met Joonas, came to tell him “Congratulations, that script is exactly like the film. “We thought about it. We needed to have these kinds of breaks in the story. It’s a ritual going into the sauna. You have a break, you go outside, get some fresh air.

RM: Kind of a POV, as if the audience left the sauna?

MH: You can think about it like that. Finnish national landscapes, sort of like soul-scapes of the Finnish people that you see there. It serves many purposes in the film.

RM: It’s a beautiful choice. How did you get the idea of putting those Santas in the sauna?

MH: Well, we wanted to have Christmas sauna, and usually it is a tradition that families go into the sauna, on Christmas, but somehow we thought about it, because Santa, well in Finland, Santas go to houses.

RM: We don’t have that in this country, they’re hired?

MH: Yes. There are big companies who rent Santas.

(All the Santas came from one Santa agency. They shot the scene on Christmas Eve, when the Santas got off work, in the oldest working public sauna in Finland.)

RM: Rent-a-Santa!

MH: We wanted to show maybe a different kind of Christmas, these Santas, what happens to them.

RM: The mobile Saunas were amazing. I saw there’s a festival once a year of these mobile saunas. I think I saw that guy in the phone booth sauna, on a tourist site…

(A man built a Sauna in a phone booth on a junction on a country road.)

MH: I think we ran into it on the Internet. I used to just google Sauna and see what came up. We found out there was a festival of mobile saunas. We contacted the people who arranged it. Through them we found all kinds of weird saunas.

RM: What about those loggers in the trailer?

MH: No, those guys aren’t loggers. The old guy with the diamond prosthetic eye, he manufactures tar out of dead wood. They collect dead wood from the woods.

RM: How did you find out about the guy who adopted the bear?

MH: Through one of the characters we shot. He was quite an interesting fellow living with bears.

RM: He had more than one?

MH: He had six!

RM: My god! You probably saw that Herzog film “Grizzly Man”?

MH: Actually, II saw it after we finished the film.

RM: How did you get the bear to pop up?

MH: The cameraman framed the picture, and he couldn’t see the bear.

We insisted that the camera not move, we really like still frames with all the focus on the men, so the cameraman had the picture framed and the bear was actually there with the guy first, then the bear got interested in the cameraman and started moving towards him. He’s shooting. He sees the bear walking out of his frame; the camera’s blocking his view. He couldn’t see where the bear went when he walked out of frame, so he just stood there waiting keeping his nerve, and then all of a sudden the bear pops up, smelling him.

RM: Did you know he would destroy that table?

MH: No we didn’t know but the guy said, “He’s gonna break it.”

(The film ends with all of the characters, one by one and finally together singing a song from Aleksis Kivi’s beloved novel “Seven Brothers.” The song is learned by every young Finn in school and is practically a National Anthem.)

RM: What gave you the idea to do that song at the end?

MH: We discussed that and we can’t remember, but I think it was quite early in the production that this idea came up. It was a last minute call to do it. We already shot the film. I tried it out, some musical demos, to see if could we mix together different singers, singing separately.

RM: It was a kind of montage, starting with one guy…he almost seemed like a boy singing a wistful lullaby.

MH: The guy who told the last story started the song, then other characters join him, it builds and builds, and you have the last choir, actually a lot of the characters that are in the film are in that choir. It’s based in a town called Kemi, in Lapland, northern Finland, and most of them are factory workers, in the paper factory where the film actually begins and ends.

RM: What about the two guys taking about a railroad accident?

MH: He was a locomotive Engineer.

RM: Now he’s a miner? Those two guys were staking a claim? That was devastating sequence. The guy was who talking about not seeing his children, his face imploded. it was like a special effect, his face went through so many changes. There were moments that were just engulfing in the movie, including this guy, the engineer.

MH: And that story! It was the first day of shooting for us. I knew the other guy. I met him actually in a sauna, where he told me the story of how his wife died, an unbelievable story, very  emotional. We had to make a demo for the film and this guy came to mind. I said OK, I’ll get in contact with him and see would he be willing to do this, you know, go to a sauna and discuss this.

emotional. We had to make a demo for the film and this guy came to mind. I said OK, I’ll get in contact with him and see would he be willing to do this, you know, go to a sauna and discuss this.

RM: And he brought along a partner and the partner told this story?

MH: Yeah.

RM: Wow. Yeah. It was a mind-blowing thing. (They decided to map the most meaningful issues in a man’s life then a look for storytellers to illustrate)

MH: Those turning points. Most people where recommended by people they knew. In order to keep the experience fresh, one of the director’s would interview a person and the other director would direct his scene.

Each interviewee could pick his partner and which sauna they would use for the interview. Surprisingly, the partners often contributed more amazing stories than the original subject of the interview.) In the editing room they realized they knew about half of the stories before they shot them.

RM: The urban sauna, were those men homeless?

HM: Two homeless guys, shot in a homeless day care center in Helsinki. They have a sauna where the homeless clean themselves and they can clean their clothes and a small restaurant where they can get some food, for a really cheap price.

RM: You felt that without seeing any of that. You knew this was an important restoration going on for them.

HM: We would hang out there, with Joonas. Quite a few times, and check out the homeless guys. We met the other guy before, whose story we actually don’t hear, because of this guy’s stories.