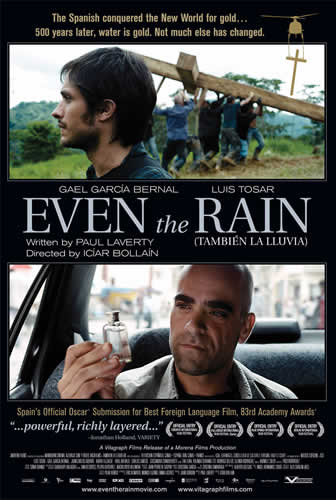

Academy Awards have included Even The Rain, the winner of Cinema Without Borders Bridging The Borders Award in the short list for the Best Foreign Language Movie Award.

Academy Awards have included Even The Rain, the winner of Cinema Without Borders Bridging The Borders Award in the short list for the Best Foreign Language Movie Award.

The following is Cinema Without borders’ interview with Iciar Bollain about making of the Even The Rain.

Icíar Bollaín Pérez-Mínguez is a Spanish actress, director and writer. Her father was an aeronautical engineer and her mother was a music teacher. She made her début when she was 15 years old. She is a member of the Academia Española de Cinematografía. She began her work in cinema at the age of fourteen as part of the cast in Victor Erice’s film El Sur (1983). Since then she has acted in fourteen films.

Hola, estas sola? (Hi, are you alone?) (1995) was her first feature film as director, a story about two young girls who dream of finding an earthly paradise, and undertake a long trip towards the sea. Flores de otro mundo (Flowers from another world) (1999) was her second feature film, which she co-wrote with Julio Llamazares. It is the story of four women who travel to rural Spain with the hopes of finding love. Her latest film as writer and director is Te Doy Mis Ojos (I’ll give you my eyes) (2003) which won seven Goya awards including Best Film. The movie is about the abusive marriage relationship between Pilar and Antonio.

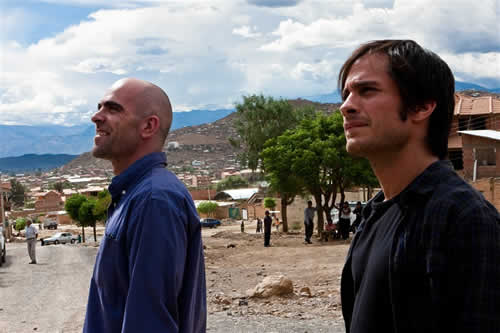

In Even The rain an idealistic young director (Gael Garcia Bernal) sets out to expose Christopher Columbus as a conquering imperialist; a man only after gold who exploited and destroyed indigenous cultures  as he pursued his fortune. His producer (Luis Tosar), seemingly oblivious to the irony, moves production of the period-piece to Bolivia in order to take advantage of the lower cost of labor there. When they arrive, they encounter a population caught up in the throes of civic upheaval as the government tries to privatize the water supply. As the crisis around them increasingly encroaches upon the production.

as he pursued his fortune. His producer (Luis Tosar), seemingly oblivious to the irony, moves production of the period-piece to Bolivia in order to take advantage of the lower cost of labor there. When they arrive, they encounter a population caught up in the throes of civic upheaval as the government tries to privatize the water supply. As the crisis around them increasingly encroaches upon the production.

Even The Rain focuses in on the director and producer, their personal evolution and unexpected reactions to the plight of those around them. Based on the Cochabamba Water Crisis of 2000, veteran Director Iciar Bollain’s powerful and layered film, set against historic and current events, lays bare the hypocrisies of a post-colonial world where injustices to the dispossessed continue unchecked. Beautifully executed period details contrasted with the raw energy of the current crisis blur the lines between fiction, reality, past and present. Vitagraph will release Even The Rain in the US in Feb. 2011.

Bijan Tehrani: Please tell me how you came up with the idea of Even The Rain.

Icíar Bollaín: The script was written by Paul Laverty. He had written a story a couple of years ago that he wanted to turn into a television series, but the project fell through so Paul kept working. Eventually, he decided to update the story and bring the timeframe to the present and then he made this connection with the waterworks and he found his way of connecting the two events; the early years of the conquest and the waterworks. So the script came to me that way, and I found it amazing and very complex with lots of levels and meat and there were many things to talk about, so I just went for it.

BT: This film seems to have two parallel levels running simultaneously through the film. How did you manage to merge these two different levels together?

IB: Well that was the way that it was written in the script, and my task was to put it all up on the screen and make it work.  When you read the script on paper, it was great, but then you are not sure if it is going to work as well on the screen; the conquest scenes and the riots would be difficult to shoot, so my challenge as a director would be to tell these three stories through the music, the acting and the way that we set up the scenes. You don’t want the audience to lose touch with the characters, which is easy for them to do when you are telling so many different stories.

When you read the script on paper, it was great, but then you are not sure if it is going to work as well on the screen; the conquest scenes and the riots would be difficult to shoot, so my challenge as a director would be to tell these three stories through the music, the acting and the way that we set up the scenes. You don’t want the audience to lose touch with the characters, which is easy for them to do when you are telling so many different stories.

BT: One of the most interesting aspects of the film is the character arc of the producer. He is one of the last characters that you think would change during the film; how were able to convey this transition so believably?

IB: I think that all the credit has to go to the actor. In order to make the transition believable, he connected and fully committed to the role, so all the credit has to get to Luis.

BT: Did you work on the script at all when it was in the development stage?

IB: No, I didn’t actually. There was another director involved who worked along with Paul for a couple of years and then he decided to do another film, and then the film came to me. Since we are a couple, we worked together occasionally and sometimes review each other’s work. The script was very sound though, and there really wasn’t much for me (as a Director) to change.

BT: How did you go about casting the film?

IB: I spent a few months working on it. Luis was easy to cast because we had worked together before and I felt that he would be great for this role. Then with Sebastian we wanted to make the casting a little bit international and we wanted to portray this reality of crossing borders. The actor had this quality of ambiguity and he fit the character very well. The Colon character was a bit tricky because it needed an actor who had an edge and character in his face and I felt that the actor, Karra Elejalde, was very good in it. We wanted the two priest characters to be very young and fresh, somehow they are a sort of activist of the time and we wanted them to be modern looking. Then the Bolivian casting was quite long and very soon we saw that we could not find the actor that we desired for the character of Daniel, and eventually we had to start casting in the street and we found an actor who had never acted in a film before. All of the other roles are played by professional actors.

BT: How did you come up with the visual style of the film?

IB: I worked a lot with the Director of Photography and we spent many days deciding how we were going to shoot it. We thought that, since the film is saying that the past and the present are not very different, and then we should not shoot it in a very different way. We did not want to shoot this period film like a romance film; we thought that it should be rough and rugged just like the riots in the streets. We also did not want to shoot the riots in a broadcast style and we wanted to make them seem very realistic. We also did the same thing with the music and its placement; the music plays under the less cinematic moments while the more cinematic scenes have no music.

BT: How was the reaction to the film in Bolivia?

IB: Unfortunately, they haven’t seen it yet. We want to bring it over, and we have been screening the film for Bolivians who live in Spain and they were very pleased. The Bolivian Ambassador was moved and very emotional because this was a very important part of Bolivian history.

BT: How challenging was it to make this film?

IB: We had a small budget and we shot the film in a very short period of time. The film looks a lot bigger than it is though. We had eight weeks to shoot it and we had some very complex scenes. The good thing is that we found great professionals there and they worked very well and the extras put so much energy into the film.

BT: How much did your acting background help you when dealing with the actors in the film?

IB: I think it helps a lot, not only with the actors, but I learned a lot about being a director from being directed. I know how hard it is to be in front of a camera and I make them feel more comfortable.

BT: Do you have any upcoming projects?

IB: I will be going to Nepal in spring to shoot a film about a Spanish woman who went over there in the early 90’s. She was a teacher and went there and found a very poor educational system and she decided to stay there and teach the children.

BT: Congratulations for making it to the Academy Awards short list and good luck.