Lionel Rogosin’s “On the Bowery” startled audiences when it came out in 1957. It still startles. His remarkable portrait of skid row, well researched and intimate, is still visceral. Rogosin spent months on the Bowery, befriending many of the men he features in the film.

Lionel Rogosin’s “On the Bowery” startled audiences when it came out in 1957. It still startles. His remarkable portrait of skid row, well researched and intimate, is still visceral. Rogosin spent months on the Bowery, befriending many of the men he features in the film.

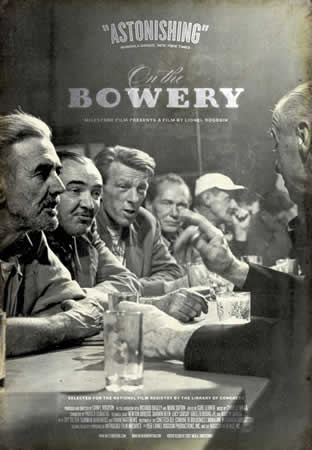

Unsentimental Rogosin treated his new pals with respect, creating a fascinating urban history. His nonjudgmental camera savors the camaraderie of the lower depths and records the daily betrayals between men with nothing left to lose. His blunt black and white photography is of a piece with the classic photojournalists of the era.

The opening sequence sets the stage. Ragged men collapse in the doorways. Cops roust a sleeping man and haul him to the Paddy Wagon.

Men sleep in doorways, carts, and delivery elevators. A drunk wakes up and looks for his shoes, clearly stolen in the night. Under the vanished 3rd Street El, drunks steal and sell clothes to street pickers for the price of a drink, downing Sterno when they can’t afford muscatel or “sneaky-Petes.”

Ray Salyer, a hard-drinking young rail worker, pulls into town. After dropping his paycheck sporting drinks for buddies at a local dive, he wanders around town with old timer Gorman Hendricks, falls down dead drunk and pal Gorman steals his suitcase. Gorman trades it for a room at a local flop, after pocketing Ray’s only valuable, his dad’s gold pocket watch. Drink  trumps honesty on the Bowery, and the next time they meet, Gorman’s giving Ray fatherly advice.

trumps honesty on the Bowery, and the next time they meet, Gorman’s giving Ray fatherly advice.

Ray tries to clean up, but can’t make it through a lonely night in the Bowery Mission, where men sleep on the floor, towing the line to win a bed in one of the rooms. He gets work unloading trucks in the meatpacking district. Frank Matthews, a first class scrounge, gives out about the drunk tank. Frank collects rags and paper in a pushcart, angling to retire on a South Sea Isle.

“Doc” Gorman finds respite in the second floor lounge of the SRO, as malarky flies over a game of dominos. The one time doctor is a trove of survival tips, which he shares with Ray, eventually staking him to a trip out west.

This is the darkest view of alcoholism on film. The Bowery we visit operates around and caters to an at-risk population of lost men, bums who survived the war, then fell through the cracks. We visit flop houses and SROS (Single Room Occupancy) whose wire ceilinged rooms offer little privacy, and watch drunks sleeping off binges on the street, rolled by their drinking buddies of the night before. There is a code of sorts. Lookouts move sleeping drunks indoors as the police sweep the neighborhood.

A raucous night in a saloon (a largely improvisational set-piece) is the fluid centerpiece of the film; snatches of Runyonesque blarney, fingers jabbing to punctuate a drunken point, close ups of cratered noses red from chronic drinking and spittle drooling from the corner of a mouth; a late night hook up with a woman eager to take Ray home, Rogosin and editor Carl Lerner create a scene worthy of Breughal.

The fate of the few women drunks is dire. Witness Ray’s dumping his new ‘squeeze’ on the sidewalk. He puts his hand in her face and shoves. It’s worse that Cagney hitting Mae Clarke in the face in “Public Enemy.” Ray could have used her protection; he’s rolled (off camera) by a couple of drunken predators a minute later.

Like Morris Engel’s “Little Fugitive”, “On The Bowery” thrilled French critics and influenced the first Nouvelle Vague films and the emerging American Independent film world, typified by Cassavettes. Charismatic Salyer, who was present at the film premiere and did TV appearances flogging the film, was offered a Hollywood career, but couldn’t be bothered, soon disappearing into the void. “One night he just hopped a train and was never heard from again. His fate is one of the great mysteries of cinema.”

Rogosin’s crash course in filmmaking was an early hybrid film, what Robert Koehler of Cinemascope calls an “in -between film.” Like Flaherty’s massaged reality, it question the boundary between fiction and doc. Rogosin, writer Mark Sufrin, and DP Richard Bagley shaped a story around the people he met, the events he witnessed, casting people to play themselves. His recreated, captured reality was so raw that the film was nominated for a Documentary Oscar and won the British Film Academy, and Venice Film Festival best Documentary Awards.

The film, beautifully restored by the Cineteca del Comune di Bologna, is touring with “The Perfect Team: The Making of On the Bowery,”

a fascinating documentary directed by Lionel Rogosin’s son, Michael.

Interviews with Rogosin (deceased), colleagues, and family members of the crew film, reveal a wonderful back-story that makes Rogosin’s soulful “On The Bowery” even more affecting.

Gorman, Rogosin’s chief guide to the Life, was diagnosed with severe cirrhosis. Rogosin convinced Gorman to lay off the bottle during shooting. Gorman, a natural yarn spinner, kept his word, willing himself to give up a fifty-glass of beer daily habit to finish the film. Gorman died a few days later from a post-shooting binge.

Gorman, Rogosin’s chief guide to the Life, was diagnosed with severe cirrhosis. Rogosin convinced Gorman to lay off the bottle during shooting. Gorman, a natural yarn spinner, kept his word, willing himself to give up a fifty-glass of beer daily habit to finish the film. Gorman died a few days later from a post-shooting binge.

Rogosin and his crew, Village denizens, were as hard drinking as some of the film’s subjects. Rogosin and writer Mark Sufrin started on 16mm, without a script. Disappointed in the results, Sufrin convinced Rogosin to work with Richard Bagley, who shot Sidney Meyers’ “The Quiet One. ” Ragosin was put off by Bagley’s grandiose persona, but the two developed an ‘uncanny” visual rapport. Bagley convinced them to make a 33mm feature. Rogosin pointed to Rembrandt’s many self-portraits as an aging man, as an inspiration of how he wanted the close up portraits of the men to look. Ray warned Rogosin that “this guy (Bagley) drinks more than I do”. Bagley, who rationed his drinks by day and binged at night, died of alcoholism at a mere 41.

Sufrin described their research in Sight and Sound in 1955-56 ” Dressed in Bowery clothes, feigning drunkenness, forced to swallow glass after glass of the foul, flat beer they serve… we became part of the smell, the gargoyle faces, the sleeping and retching, the whole agonized disturbance.”

Rogosin discovered that mining the stories of Gorman, Ray and Frank, gave him hours of spontaneous dialogue he could use. His inside job, allowed his characters to speak for themselves. They shot for 3 or 4 months, in the hottest summer on record. Eventually they wrangles permits to solve police harassment. The police would break up “the crowd” as the crew filed street sequences or pick up Rogosin’s “characters”, shave them and cut their hair, forcing the filmmakers to shoot around them untll their hair and beards grew out. Ironically, as they shot, the city was already beginning to take down the elevated train that created the purgatorial Bowery. This film is it’s pungent portrait.

Activist Gerda Lerner, widow of Bowery’s editor Carl Lerner, is an interesting addition. Lerner pioneered both Women’s and African American History curricula, teaching arguable the first Woman’s History Course in the early 60’s at New York’s New School for Social Research.

Rogosin founded the Bleecker Street Cinema in 1960, one of New York’s most influential Cinema centers, championing the New American Cinema. His Impact Films introduced the Czech New Wave films to American audiences. Rogosin’s undercover record of apartheid, 1960’s “Come Back, Africa” launched Miriam Makeba’s career (he bankrolled her early tours.).

His anti-nuclear war film “Good Times, Wonderful Times” was a staple on college campuses during the Vietnam War protest period.