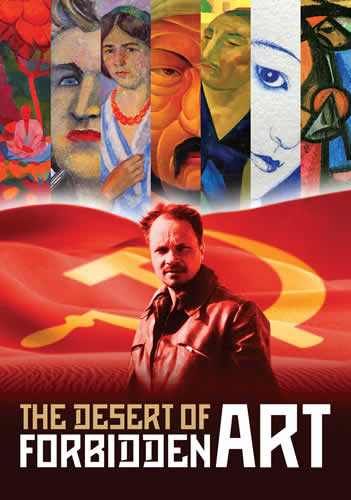

The Desert of Forbiden Art, tells the incredible story of how a treasure trove of banned Soviet art worth millions of dollars is stashed in a far-off desert of Uzbekistan develops into a larger exploration of how art survives in times of oppression.

The Desert of Forbiden Art, tells the incredible story of how a treasure trove of banned Soviet art worth millions of dollars is stashed in a far-off desert of Uzbekistan develops into a larger exploration of how art survives in times of oppression.

During the Soviet regime, a small group of artists remain true to their vision despite threats of torture, imprisonment and death. Their plight inspires a frustrated young painter Igor Savitsky. Pretending to buy State-approved art, Savitsky instead daringly rescues 40,000 forbidden fellow artist’s works and creates a museum in the desert of Uzbekistan, far from the watchful eyes of the KGB. He amasses an eclectic mix of Russian Avant-Garde art. But his greatest discovery is an unknown school of artists who settle in Uzbekistan after the Russian revolution of 1917, encountering a unique Islamic culture, as exotic to them as Tahiti was for Gauguin.

Bijan Tehrani talked to AMANDA POPE and Tchavdar Georgiev directors of The Desert of Forbiden Art about their film.

Amanda Pope‘s directing, producing, writing, and editing credits over her more than 20 year long career include award-winning documentary, dramatic, and social advocacy  programs. Her work has focused on the dynamics of creativity in fine art, public art happenings, urban design, theatre and dance. Her award-winning public television documentaries: Jackson Pollock Portrait, Stages: Houseman Directs Lear, and Cities for People have all been broadcast nationally on PBS. Most recently she directed The Legend Of Pancho Barnes And The Happy Bottom Riding Club about a pioneer woman aviator. Her program series, Faces Of Change, documented grassroots reformers and emerging leaders in the former USSR.

programs. Her work has focused on the dynamics of creativity in fine art, public art happenings, urban design, theatre and dance. Her award-winning public television documentaries: Jackson Pollock Portrait, Stages: Houseman Directs Lear, and Cities for People have all been broadcast nationally on PBS. Most recently she directed The Legend Of Pancho Barnes And The Happy Bottom Riding Club about a pioneer woman aviator. Her program series, Faces Of Change, documented grassroots reformers and emerging leaders in the former USSR.

Tchavdar Georgiev has produced, associate produced or edited award-winning fiction and non-fiction films as well as TV programming for ABC, PBS, History Channel, National Geographic, Oprah’s OWN Network, Channel 1 Russia and MTV Russia. He was one of the editors on the documentary We Live in Public (Grand Jury Prize at Sundance). He edited Alien Earths for National Geographic (nominated for an Emmy), the narrative feature Bastards (MTV Russia awards for best film) and the documentary One Lucky Elephant (best documentary editing award at Woodstock Film Festival.)

Bijan Tehrani: How did you originally come up with the idea of making The Desert of Forbiden Art?

Amanda Pope: In 2000 I was asked by the Eurasia foundation in Washington to go and do short portraits of emerging leader in the former Soviet Union, it was going to be a really tough trip since we were going to be visiting seven countries in five weeks and I really didn’t want to work with anybody my age because I felt that they would complain; so I decided that maybe we should go with our recent USC alums who would consider this as much as an adventure as I did. Tchavdar had been my student and I knew that he spoke Russian and was totally up to speed and was a professional and that it was happened. So the three of us, including our cinematographer who was recent alum from our film school, found ourselves in Uzbekistan and we were told about this incredible museum and in the middle of the desert.

Tchavdar Georgiev: I remember clearly that Amanda was really excited about finding this information and I remember asking “Amanda what are you talking about? There will be nothing of any value in the middle of a desert in Uzbekistan”. So we never went, but two weeks later we were in Moscow and we were visiting the flee market there and there was this shady salesman who was selling these Russian art books and I felt that it was really interesting. I was being really cocky and I pretended to know about everything that was in the book and I asked if he had anything that I had never seen before. He eventually pulled out this really old book called Avant Garde on the Run, both of out jaws dropped and seven years later we have the film.

BT: How challenging was it to make The Desert of Forbiden Art?

BT: How challenging was it to make The Desert of Forbiden Art?

AP: We had to see if we had some living characters, this incredible collector had died in 1984, we started checking with the new director and saw that she had spoke fluent English. We interviewed her on Skype and saw that she was very dynamic, she made a chance decision as a University student to study English because she heard and fell in love with the Beatles; the fact that she was fluent in English was important to she being able to stand up for the collection and bring world attention to the collection. The next step was finding out if we could actually get visas an eventually find out way into the country.

TG: It was fairly challenging, we got a small grant from CEC Artslink in New York which is a foundation sponsoring work between the former Soviet Union and America, and we took a small crew and went out to Uzbekistan. We were told that in order to shoot in the museum we would have to get permission from the minister of culture and sport who was a former Olympic wrestler. So we were negotiating for several days and finally they allowed us to shoot in the museum, but we didn’t know flying into Uzbekistan whether or not we would be able to shoot.

AP: The process was incredibly difficult and that is why it took so long, is the second largest collection of Russian Avant-Garde, but a lot of the works that were rescued by the museum were done by artist who were not known, that’s why its so very special that he was able to save their work; because the artist weren’t known, the foundations in the country were not stepping forward to give us grants. USC gave us a grant which then interested other societies and foundations, so we made two trips to Russian and in between we were raising money.

TG: Some of the other challenges, just to give you an idea, as we were trying to piece together the story we were dealing with a main protagonist that who was already dead and he didn’t write to many things down in his diary because during his time it was dangerous to write things down because of the KGB and things that were written down could be used against you; so our main protagonist was dead and the artist were dead, but their children were around. So we had to use as many resources that we had,; one of the artist in the film who converted to Islam, we got his writing out of the KGB archive, when he was arrested the first thing that the KGB did was to put a blank sheet in front of you and tell you to write your entire biography; it was an intimidating technique that they used and it also enable them to get more  information out of you. This autobiography is where we got a lot of our information about theis particular artist.

information out of you. This autobiography is where we got a lot of our information about theis particular artist.

AP: Savitsky was not wealthy; he had to get the money from the Soviet government, the same government that was banning the paintings. He was very foxy and he manipulated the system. We filmed at a monastery and inside the monastery was a prison of paintings, painting that were considered unacceptable by the Soviet government. We went to the monastery and we found the director who had been the director when the Soviets were still in power and he described Savitsky coming to this prison for painting and everybody in the archive, who were supposedly against the style of painting, help Savitsky get paintings out of the archive so that he could take them to his museum. So it was not all a negative picture in the times, there was always an underground of people who love art and were eager to let it survive.

TG: The irony of it is that in order for Savitsky to be able to do this he befriended the local communist leader who gave him money under the table and he closed his eyes a little bit to allow Savitsky to do all of these things. The museum was the only museum in the Soviet Union that was exhibiting illegal/forbidden art funded by government money and it was the only museum that did not have a board comprised of communist party members that did not control every painting that was displayed.

BT: The Desert of Forbiden Art has several different layers, one being about the collector and his adventure and the other is about the art itself. How did you balance these different stories?

AP: This was Tchavy’s mastery as the editor, this was a very difficult film to edit because we did not wasn’t to simplify it too much and we wanted people to have a feeling of the time because if you didn’t understand the history and not able to put yourself in that time, then you would not get the time, suspense and the achievement of that story. We were weaving the stories through the archival footage, through the stories of the children and the still photos that were taken at the time. Tchavy had this wonderful idea where there was a situation where the women of Uzbekistan were veiled but when the Soviet’s came in the veils were taken off and we found this wonderful archival footage of these women burning their veils and then we had this wonderful footage of them building a canal and happily taking part in building the canal; it was then Tchavy’s idea to take a scene from a very famous Russian film.

TG: Ironically the film was forbidden, but it was kind of the Russian version of a western which we call an Eastern. It takes place in central Asia and it is the story of a Russian Soviet Red Commissar who is in charge of escorting the 9 wives of the local Taliban leader. Through that there is this whole irony of the Soviet Bolshevik culture clashing with the Islamic culture. We found a lot of clashes like this and one of the most important questions that we try to ask ourselves is what it was like to be in these artist shoes when they were creating this work. We knew that there must have been someone photographing these artists as they were painting and through Amanda we were able to discover this incredible Photographer named Max Penson, he was the  main photographer for the main newspaper in Uzbekistan and was in charge of documenting the advances of the Bolshevik revolution in Central Asia. His grandson actually lives in New York actually posted his photos online and you can see this great transition from a feudal Islamic society to a Soviet state, so these photos gave us a way to show exactly what it was like to live in those times.

main photographer for the main newspaper in Uzbekistan and was in charge of documenting the advances of the Bolshevik revolution in Central Asia. His grandson actually lives in New York actually posted his photos online and you can see this great transition from a feudal Islamic society to a Soviet state, so these photos gave us a way to show exactly what it was like to live in those times.

AP: We also had a wonderful composer who lives here in LA, named Miriam Cutler who has been the Sundance composer and resident for a number of years. She loved world music and when she saw the film she signed on and created such a wonderful score; she used the instruments of central Asia and Russian and weaved them into the score. We wanted our audience to have the experience of living in these times.

BT: Do you guys plan on doing another film like The Desert of Forbiden Art?

AP: We were told at the beginning that this was an impossible film to make and that was just another thing that we love to be told and it pushed us to want to do it. We want this collection to be known and we want people to look into their own lives and find those little treasures that they are looking to protect.

TG: As we were going around the world the films were screened in several different countries and festivals, we would hear from people in the audiences about their own art treasures. For instance we were in Brazil and the audience told us about a contemporary art movement that was crushed in a similar way by the Brazilian dictatorship.