In the 70’s, I taught an infamous class: “Footage Fetishism: The Politics Of Film” at the Pacific Film Archive (then run by Tom Luddy). My house became an unofficial Artist in Residence house, where I hosted many international filmmakers for extended periods of time: Nick Ray, Krystoff Zanussi, Dusan Makevejev, Jean Eustache, etc.)

In the 70’s, I taught an infamous class: “Footage Fetishism: The Politics Of Film” at the Pacific Film Archive (then run by Tom Luddy). My house became an unofficial Artist in Residence house, where I hosted many international filmmakers for extended periods of time: Nick Ray, Krystoff Zanussi, Dusan Makevejev, Jean Eustache, etc.)

Errol Morris (a recent Madison grad) arrived in Berkeley. His stories of visiting mass murderer Ed Gein in a hospital for the Criminally Insane disturbed a lot of the PFA folks. He was brilliant. I vouched for him, and because Herzog and producer Walter Saxer were staying in my guest rooms, let Errol stay, in his vehicle, in my driveway. As I remember it, Herzog (who loved the obsessional) invited Errol to come to a shoot. He later worked as an assistant on “Strozek”, and the rest is history.

I was a big fan of the early Werner Herzog films, which we repeatedly brought in through the Goethe Society and championed at the PFA. He was a protean artist, taking stylistic leaps with each of his early films. From “Signs of Life”, “Even Dwarfs Started Small”, his first feature doc “Land of Silence and Darkness”, through “Aguirre”, each film was different. The only connection was his cool ironic stance and his shots of repetitive images, like the windmills in SOL, etc.

I was disappointed in “Casper Hauser”, the first film in which he borrowed shtick from earlier work, giving it a sort of magisterial elegiac (albeit canon building) gloss you’d expect from an old film maker at the end of his career, all of which lead to his Hollywood produced “Nosferatu.”

Herzog’s deadpan, experimental “Fata Morgana” was a special case in point. The almost clinical framing of his subjects (two cabaret artists in the pathos filled backwater night club) seemed to presage a new way of filmmaking, a sort of rube soft-surrealism.

Herzog abandoned the experiment but I believe Errol Morris developed his early comic style (“Gates of Heaven”, 1978 “Vernon, Florida”, 1981) inspired by this precursor to ‘Post modern Irony.”

I put this to Errol, recently and he replied, “I always quote a Paris Review interview with Gabriel Maria Marquez. He comments on his first reading of Kafka’s Metamorphosis. “I didn’t know you were allowed to that.” “Fata Morgana” had a similar effect on me.”

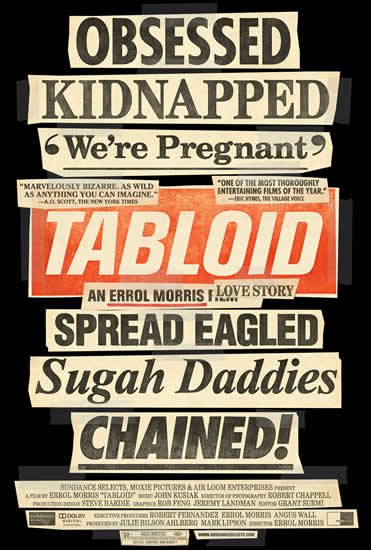

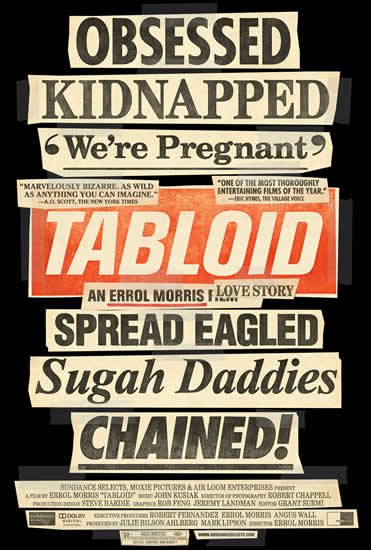

Morris’s work has redefined the nature of documentaries. For decades he’s been working from the documentary side towards that hybrid style, somewhere between doc and fiction, that Robert Koehler calls the cinema of the in-between. “Tabloid” is a sort of comic summation of this journey.

Robin Menken: I remember you worked as a P.I

Errol Morris: I was a private investigator briefly in Berkeley and I worked for David Fechheimer (note: dean of SF P.I’s) and Jack and Sandra Pallandino (note: Patty Hearst, People’s Temple case, DeLorean and Bill Clinton defenses) but that was very briefly. That was probably in the 70s and then my film career, which never amounted to a film career per se, went completely belly up and I had to find a way of earning a living, so I worked as a private detective in New York in the early 80s.

RM: Did your detective work influence your interview style with film subjects?

EM: I think it’s the other way around. I started interviewing murderers. I interviewed Ed Gein (note: Gein, who fashioned furniture from victims’ body parts, was the inspiration for Psycho’s Norman Bates, “The Chainsaw Massacre” and “Silence of the Lambs”) and I interviewed a whole lot of murderers in Northern California and Wisconsin. It goes back several years; I had a relationship with Ed Kemper. I’d gone to all of these trials. I was going to write a PHD thesis on the insanity plea. In those days there were three mass murderers in northern California, the Big Three; Ed Kemper (note: the Coed Butcher) Herbie Mullen and John Linley Frasier. I had gone to part of the Kemper trial and part of the Mullen trial and…they all involved the insanity plea. I was interested in writing about them. I started interviewing people and, I believe, those were my first real interviews and I went back to Wisconsin. I had been an undergraduate at Madison. I started interviewing people in Wisconsisin, and I developed this whole style of interviewing where… I remember the tape recorders very well and everything was done with cassette tape recorders, Sony TC 55 and TC 56, I believe. I would play this game where I tried to say as little as possible, so I had tapes that I was particularly proud of where my voice wasn’t on the tape. I would see if I could get the person I was interviewing to talk for a full hour, without my voice being on the tape.

The idea was just this pure stream of consciousness, for want of a better way to describe it, the “Joycean interview”, and that certainly informed “Gates of Heaven”. It became the idea behind “Gates of Heaven”, and I never included my voice in editing these movies.

I wanted to publish a book. No one was really interested in publishing my writing. I stopped writing for years and years and years. And now I’m publishing all these books. I have a book coming out September 1st, from Penguin. “Seeing is believing”. I have a second book coming out from Penguin on the Jeffrey MacDonald murder case. I have a third book coming from the University of Chicago Press, based on a set of essays I did for the New York Times, called “The Ashtray”. So I’m writing a lot.

Q. What books have influenced your work?

EM: One good example, I’ve always been a fan of Frank Norris. I’ve read everything Frank Norris has written, and he wrote a lot. It is interesting, and I’ve always objected, they always pair “The Octopus” and “The Jungle” together They are really disparate. They come from different traditions altogether, and they have nothing to do with one another. What I didn’t understand was that there was a relationship between Norris and Dreiser. And why was I thinking of Norris and Dreiser, because Joyce McKinney told me that when she was in high school, she had read a short story by Theodore Dreiser called “The Second Choice”, and I got the short story and read it and started compulsively reading Dreiser. “The Second Choice” is just an amazing short story. It’s one of the amazing short stories. Tragic. It’s not by accident that Dreiser called his greatest novel “An American Tragedy.” It’s about a woman, the short story. It starts with a series of letters written by her lover. It’s clear that the guy really isn’t interested in her. She is completely in love with him. He’s not in love and there is a man who wants to marry her but she is not particularly interested. She doesn’t want to end up like her mother in a boring marriage. In the end she settles for her second choice. She settles for a guy she’s not really in love with and she ends up like her mother. To call it bleak is an understatement. It is one of the darkest American short stories. And Joyce told me about this. She told me she had decided that was not going to happen to her. She was never going to end up as this Dreiser character in a loveless marriage, etc etc. etc. And this is my question, a propos of books, whether what happened to Joyce is worse.

Q. When he was taken away, when Kirk disappeared, why was California her first stop?

EM: I don’t know, I really don’t know. Maybe she believed that she could earn a living in California. I don’t know why anyone comes here.

Q. In the earlier films you were known for portraits of eccentric people, and then the Abu Graib movie seemed like change of pace for you. You were trying to break down the nature of evil and what drives people to take part in that kind of thing. How do you decide when to be funny and when to be serious?

EM: I think “The Thin Blue Line” was kind of funny”, not as funny as this. I took out a lot of the funnier stuff in the Abu Graib movie. Perhaps a mistake. I don’t know. These stories have logic of their own; it’s not really a decision, per se. Once I made a decision to put Joyce on film then things follow in due course, the other interviews, the material. The material certainly is funny, it is sad and, I would say also it’s sick.

Q: It’s a love story and also, to a certain extant, it’s a Film Noir.

EM: I like the idea of it being a Film Noir and I never even thought of that until the interviews this morning. I love Film Noir.

I reconnected with Dennis Jakob (legendary editor/consultant “Apocalypse” etc). I talk to Dennis all the time, and I made a movie with Dennis that was shown at Telluride last year (“Dennis Jakob Unplugged”.)

My introduction to Noir, of course, is the Pacific Film Archive. One of the things that has always fascinated me about Noir is that people really don’t have control over their lives in Noir, they’re part of some infernal tapestry of design, and there is a sense of inexorability, as in this story.

The bookends, to me, are the strongest element. I feel very lucky to have stumbled on that material. Trent Harris had filmed material with Joyce in the early 80’s, and very kindly allowed us to use that material, which is at the very beginning and the very end of “Tabloid” The material of Joyce reading from her still unpublished, incomplete book is amazing because it is a self-fulfilling prophecy among other things.

Q; In Joyce’s mind she was actress (she probably meant on the adult side.) I found that fascinating, because there was all this proof of what she did, but in her mind, she didn’t do anything.

EM: I don’t know about any of it. I think there’s at least a possibility that she’s a virgin.

Q: Tell us about the Mormon guy.

EM: The Mormon guy (Troy Wiliams) he came to us because he had considered interviewing Joyce because he had a show on the radio in Salt Lake City. And, at first I though he was not appropriate for the movie, because he is not really part of the story, but he was great. He turns out to be essential.

Q: Did you follow the KcKinney Trail

Q: Did you follow the KcKinney Trail

EM: No, That wasn’t known over here.

Q. Why didn’t you ask Joyce how she made her money to get from Boston to LA? That seems to be at the heart of the controversy.

EM: I’ll give you one simple reason why I did not ask the question, because I did not interview Trent Gavin until long after I interviewed Joyce. The whole LA story was unknown to me until months after i did the initial interview with Joyce. I am not sure, and it is self serving for me to say at this point, how much I would have learned asking her questions about LA, because she is not really inclined to talk about it, at least from what I’ve seen reading interviews with her after the fact.

People love adversarial journalism for whatever reason, like you’re supposed to sort of ask the difficult question or back the person against the wall. I think I would have learned very, very little by asking that question. I certainly wouldn’t have cleared up anything, ultimately. I suppose if she’d gone into enormous detail about being a sex worker, but I think that the material is there, sorry.

She’s had lots of problems with the film and she said, I believe, that she thought that she was going to be the only person interviewed. I haven’t had the chance to say this to Joyce directly, and I would be perfectly happy to, that this is all a part of her story. For me not to talk to Kent Gavin or Peter Tory, It would come back to haunt all of us. It’s not as though that material was going to vanish or go away. It is part of her story, and I think I’ve told her story in a very complex and interesting way that works to her benefit, not to her detriment.

(Note: McKInney has repeatedly attended festival screenings of “Tabloid” where she heckled from the audience. She has threatened to sue the film, which she has described as a ““celluloid catastrophe”. In an interview with John Anderson of the New York Times, Morris explained, “I don’t know how else to describe it. It is part performance of course. We used to joke if there was an Academy Award for best performance in a documentary, she’d win.”)

EM: I think that she is kind of an amazing romantic heroine of sorts, but I don’t know if she’s a virgin or not, but there’s always that possibility that she never had sex with Kirk. I don’t know.

Q: With all the weird photos and ads and everything, you think there was a possibility she wasn’t gong to do anything?

EM: Kent Gavin says in the movie, “She never had intercourse!”. So do I think there’s a possibility? Yes, I do.

Q: How did you find out about this crazy story?

EM: An AP wire service story article in the Boston Globe

Q: in 1977?

EM: No very recently, I knew nothing about it years ago.

Q: The dog-cloning story, right? That’s where it started for you?

EM: The AP wire service story concluded with a small piece of information that the dog cloning might be connected to this 30-year-old sex in chains story.

Q: So first instinct, what grabbed you right away? made you think this was a film, the dog cloning bit or the actual tabloids of the 78 story?

EM: Both, a combination of them caught my attention.

Q: How long does it take for you to develop something until you finally say, hey I got something with this?

EM: I saw the story and I thought this could be interesting. Originally I was thinking about this almost as a first person story, I called Joyce. She wasn’t interested. She was in North Carolina, then, a good part of a year later I was offered deal a Showtime to do a new series and the title of the series was Tabloid and I thought this could be the pilot or the first show in that series.

We contacted Joyce who was now in Southern California. I was in Southern California and she came in for an interview and we filmed that one interview. That was it. I had only two meetings with Joyce McKenna: one was that initial day in the studio shooting that interview, and once was on stage with her after a screening in New York of the film. Other than that I really haven’t crossed paths with her.

Q: How long did that interview take?

EM: 6 hours or so.

Q: Straight through, did you stop a lot?

EM: Um, I can’t really remember all of the details, we stopped and started. It was inevitable. But it was done basically during one day.

Q: Did you observe her reactions to the film in New York, after it was over?

EM: Well she was on stage with me.

Q: How did she react?

EM: Well she has complained about the film, complained that the film was not completely oriented against the Mormon Church, as if that was the reason I was making “Tabloid”, to attack Mormons and Mormonism. In fact, that was not the reason I made the film. I know that whenever you do a story about a real person there is going to be trouble of some kind. It’s like any human relationship. except there’s the public thrown in as well. People have expectations of what they would like the movie to be versus what the movie is. It’s inevitable.

Q: Have you had that experience with other documentary subjects before? Let’s say Fred Leuchter Jr. (Holocaust denier, Mr. Death). What did he think?

EM: Well of course, I gave Fred the opportunity to see the movie. We showed him the entire movie. I put him on the Interrotron (note: Morris’s invention allows interviewees to watch Morris’s face on live video feed on a screen, similar to a tele-prompter) while he watched the movie, and then I interviewed him. I said to him explicitly, “You know, Fred, I don’t agree with any of this stuff. I believe that poison gas was used at Auschwitz, and your so-called proof that it was not is not terrible compelling.”

Q: So you were direct with him?

EM: It’s the most direct that I have been with anybody. No I believe I was direct in “The Thing Blue Line”, too. There’s a factual matter, you are making a claim about something that happened or didn’t happen. If the Dallas police say that Randall Adams shot Police Officer Robert Wood, that is a true or false claim, and finding the answer to that is at the center of the enterprise. Finding an answer to Fred’s claim that poison gas wasn’t used at Auschwitz-Birkenau is at the center of that story. Make no mistake.

Q: In this case, you kind of leave things more up in the air…

EM: For good reason, because there are answers in history, but sometimes we can’t know what those answers are. I’ll give you a perfectly good example. Historical evidence is perishable. If someone destroys all historical evidence for any given event, it is going to be pretty hard to come to a conclusion about what really happened. It doesn’t mean that something actually didn’t happen, but we may not be able to ever determine what that is..

Q: You have two people here, the tabloid people lost their evidence and Joyce lost her evidence.

EM: That is absolutely correct, sir. A lot of people losing evidence and you have people dying. AJ… take the kidnapping itself, Kirk had a partner, we tried to get the partner to talk to us but, supposedly he never really saw the kidnapping per say. So there’s KJ, her friend and partner in crime, if you like. KJ is dead, can’t interview him. There is Kirk, who refused to be interviewed and then there is Joyce. Do I know ultimately what happened? Was he taken by force, either in the ‘love cottage” or from his missionary work? I don’t really know, ultimately.

Q: What about the chloroform, did she have that?

EM: I sort of buy Jack’s and Shaw’s claim that she had the handcuffs, chloroform and the fake gun.

Q: But I don’t remember her addressing that or denying that.

EM: She denies that she took him by force, yes. I mean she uses her whole marshmallow in the parking meter argument and she claims, it’s in the story, that Kirk was manipulated by the Mormons, and that she was, in fact, an innocent party in this. She was rescuing him from a cult.

Q: Is it fascinating to film stories about difficult dilemmas, where both parties have ample room to be wrong?

EM: In what sense? Was it wrong for Joyce to force Kirk’s hand? Was it wrong for Kirk to abandon Joyce? There is so much ambiguity in this story, of every variety and stripe. That’s one of the reasons I like the story. In my job as a filmmaker, if I can find some underlying truth or reality that’s essential to the story, I go after it. In “The Thing Blue Line’, in “SOP”, in “Mr. Death”, I went after it, in all three of those instances. This is a different kind of a story; in the sense that what really fascinated me in this story are these competing narratives at war with each other. Various tabloid journalists, both with a need to tell their own version of reality, and Joyce, you have one more version, and the ongoing uncertainty about what really transpired in all of this. It’s casting a net around that, making sure the ambiguities are in the story, so that people can think about the mysteries. The mystery itself. I have been obsessed by this crazy story. I’m going to interview Steve Moscowitz. I’d like some answers, now. ( Note: Moscowitz drove Mckinney and her girlfriend to their adult calls and listened in from the car to make sure the jobs never got rough or went beyond Mckinney’s boundaries. A journalist gave Errol Steve Moscowitz’s contact info.)

Q: Ambiguity, was that at the heart of your decision to not use re-enactments?

EM: Reenactments, people are completely confused about this nonsense. For some people, film reenactments are designed to remove ambiguity, but they have never served that function for me. They serve the function of calling attention to the mysteries, uncertainties, ambiguities. I wrote a set of essays for the New York Times on reenactments.

The milkshake in “The Thin Blue Line”, I’m not reenacting someone throwing a milkshake. That’s not the reason that exists in the movie and people who thought that, I believe, are retarded. The reason that exists, is because I was addressing a question that obsessed me at the time, and still obsesses me.

You have a quintessential mystery. Five people take the stand in this man’s capitol murder trial and say, “That’s the man that I saw as I was passing by in the roadway that night.” There’s the policewoman, there’s David Ray Harris, who actually hah hah ha, turns out to be the real murderer. He’s a great witness, and these three guys who were these whacko witnesses on the roadway at night.

One of the central questions in the movies was did the policewoman get out of the police car? What did she see? What was she in a position to see? She buys a milkshake at a Burger King. She gets in the police car. They see a car traveling without its headlights. They do a routine traffic stop. Her partner gets out of the car, walks up to the driver’s side, gets shot five times and killed. The car speeds off. The police woman claims, and this is all in there in the movie, maybe it’s not as explicit as it should have been, the police woman claims the had gotten out and that she was standing at the rear of the suspect’s vehicle. So she was in a position just to look in the back window. The police do a crime scene diagram and you see where the police cruiser was parked and you see where the milkshake was thrown. It’s right outside the door of the cruiser. So you are asked to reconstruct for yourselves what you think really transpired. If you were getting out of the car with your partner, you were either going to carry the milkshake with you or put it down on the floorboard.

Q: No one likes to waste a good milkshake.

EM: No one likes to waste a good milkshake. However, if