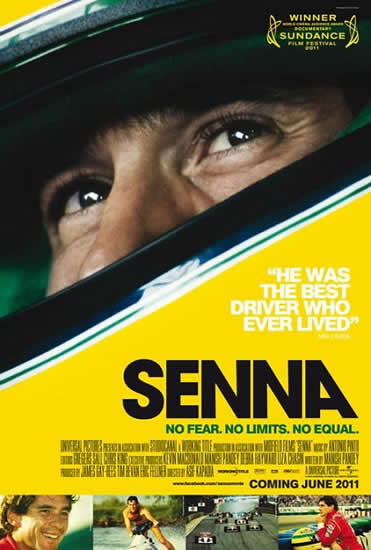

Senna is a very powerful documentary on life of Brazilian Formula One racing driver Ayrton Senna, who won the formula1 world championship three times before his death at age 34.

Senna is a very powerful documentary on life of Brazilian Formula One racing driver Ayrton Senna, who won the formula1 world championship three times before his death at age 34.

Asif Kapadia, director of Senna is known for his visually striking films. He has an interest in exploring the lives of ‘outsiders’, characters living in timeless, extreme and unforgiving circumstances or landscapes. His films have been awarded and distributed internationally and shown how versatile and expressive British cinema can be. Born in Hackney, London in 1972, Kapadia studied filmmaking at the Royal College of Art where he first gained recognition with his short film The Sheep Thief (1977) telling the story of a gifted street-kid and the family who take him in, made with non-professional actors in Rajasthan, India. The film won many awards including Second Prize at the 1998 Cannes International Film Festival (Cinefoundation), the Grand Prix at the 1997 European Short Film Festival in Brest and Best Director at the Poitiers Film Festival 1997. Kapadia’s distinct visual style continued with his first feature The Warrior shot in the deserts of Rajasthan and the snow capped Himalayas. The Warrior was championed in the British Press as ‘epic’ and ‘stunning’ and won two BAFTA awards for Outstanding British Film of the Year and The Carl Foreman Award for Special Achievement by a Director in their First Feature. Far North (2004) premiered at the Venice Film Festival, based on a dark short story by Sara Maitland. Kapadia used the epic and brutal arctic landscape to show how desperation and loneliness drive a woman to harm the person she loves the most.

Bijan Tehrani: How did you come across the subject of Senna?

Asif Kapadia: The project originated with a producer James Gay-Rees, who had the idea to make the film as a documentary. James’s father had worked at a company that sponsored Senna’s black Lotus car, so he would come home from work and talk about Senna and just rave about how this man was something special—that there was something otherworldly about him, even at a young age. It wasn’t until 2004, when James saw an article in the newspaper, in the times of London Newspaper, where there was a journalist talking about Senna in the same way that his father used to talk about him. James thought that maybe there was a film here; there was something very special about Senna that could become a documentary, and that was seven years ago. What happened then was that he spoke to a company in England called Working Title Films, and they agreed to finance the film and he met a writer who was a very big Senna fan and he had seen every race and read every book and knew everything! So James and Manich approached the family in Brazil in Sao Paolo and managed to pitch the idea for the film and to the family, and they were very moved and agreed to allow permission and James managed to make a movie. Then they had to go to Bernie Eckleston, who owns the footage. He owns the commercial rights, so they had to then do a deal with Bernie Eckleston for access to material, so all of this permission took 2 years. Then, in 2006, the producers approached me to direct. Now, my background is in drama and I had never made a documentary before, so my aim from the beginning was to make the film like a feature film—not like a television documentary. We spent the next few years looking at footage and putting it together and editing and doing our interviews and it took nearly three full years of researching, editing, and interviewing people to make the film that we have now.

BT: Just knowing about the feature films that you have done in the past, it seems that this would be a very challenging project for you. What was it that attracted you to the subject?

BT: Just knowing about the feature films that you have done in the past, it seems that this would be a very challenging project for you. What was it that attracted you to the subject?

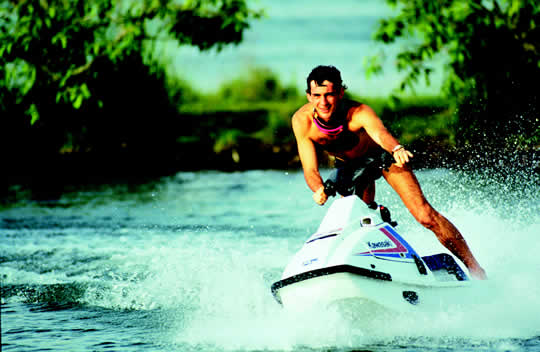

AK: I’m a big sports fan. I love sports and I was into sports long before I was into cinema, so I remember Senna. I remember the rivalry; I remember the accidents. I was watching him live, so I knew enough about the sport but I didn’t know much about the man. I didn’t really know that much about him away from the car, so for me there was some excitement to do something very different to what I have done before, and also there was something about making a film about a real person who was a huge hero to Brazil and to many people around the world. So that was the challenge: I was interested to try something slightly different and then as soon as I started looking at the footage, then I realized the potential of the film could be so special because everything in his life was being documented—everywhere he went, he was so famous, there was a channel following him. There was Fuji from Japan following him and the sport was such a huge sport all over the world. Everywhere he went there was a camera! I knew we could make a really interesting movie that could work hopefully, not only for the fans of Formula 1 and racing, but also for many people in the U.S. who had never heard of Senna and had never seen Formula 1 and don’t like the idea of driving and racing. I just had an instinct early on, when I saw the material, that we could make a very, very powerful film.

BT: What made you decide to take a dramatic approach to this film?

AK: It’s interesting because, at the festival I have to work from my instincts, and my instincts are as a drama person, so my instincts are to tell the story with the footage always. So none of my films have talking heads and voiceovers and narrators, so I don’t really come from that style of filmmaking. I like to show, not tell. Secondly, there was a writer—Manish Pandey—who is very, very knowledgeable on the subject. He wrote an outline and had a storyline, which is only ten pages long, but it had all of the key moments in Senna’s life and his career, and we started with that. Then we started looking at the footage and what would happen is, we would do an edit with the material that we could see—much of which we found on YouTube or video tapes—and then we would re-write the script and the script would suggest something about his character or we could only show a certain amount of racing footage. So we focused on these key races and had a constantly changing script. We never really had a screenplay because it never would have worked like that because documentaries are not like that, but because we have a knowledge of drama , James, the producer and myself managed much more drama people, we were naturally working with the naturally kind of three act structure. From the beginning, the rise of the young man coming from Sao Paolo and winning the world championship—you know, in many films that would be the end of the film, but this film, that was just the beginning. He had this amazing library, which was very famous, and in the final act we knew we would slow down the structure and go much more into detail of what happened on this very, very cursed weekend in Manila. So we always had this idea in mind of the structure and we had this idea of leaving a hole in our film. We couldn’t just write a scene and go and shoot it and then get someone to do the voiceover, we had to find a scene somewhere in the world that would fill that hole in the movie. What would happen is that we would have researchers in Japan, in Rio, in Holland, and other nations—and we were in London looking at the Formula 1 archive—and everytime we filled a hole in our story, something else would turn up that we did not know existed, and so we would have to put that in the film and the script would have to be re-written. We would just go forward with how we worked. I didn’t want talking heads, even though conventionally that is what you are supposed to do. I felt that there was a better and much more dramatic and emotional film to be done without cutting out the present, and by doing that it is much more difficult, it takes longer and is much more expensive. We only had deal for forty minutes of archive footage from the Formula 1 people, so I was cutting film often because my first cut was seven hours, my second was five hours long, then I had a three hour cut, and then we realized that we needed to make a change on a different scale. The producers agreed that the only way we could do this film is if we went back to Bernie Eckleston to renegotiate to see if we could have eighty minutes of footage and not forty. If we only had the forty then I was going to have to shoot interviews and cut interviews. I did shoot interviews eventually, but I just chose to keep the audio only, just the voices of people. I did not want to use the picture because I wanted to stay in the moment and, added to that, I could interview everybody but not Senna, and to me this would defeat the purpose; this was Senna’s story and we wanted him to narrate his own life story.

, James, the producer and myself managed much more drama people, we were naturally working with the naturally kind of three act structure. From the beginning, the rise of the young man coming from Sao Paolo and winning the world championship—you know, in many films that would be the end of the film, but this film, that was just the beginning. He had this amazing library, which was very famous, and in the final act we knew we would slow down the structure and go much more into detail of what happened on this very, very cursed weekend in Manila. So we always had this idea in mind of the structure and we had this idea of leaving a hole in our film. We couldn’t just write a scene and go and shoot it and then get someone to do the voiceover, we had to find a scene somewhere in the world that would fill that hole in the movie. What would happen is that we would have researchers in Japan, in Rio, in Holland, and other nations—and we were in London looking at the Formula 1 archive—and everytime we filled a hole in our story, something else would turn up that we did not know existed, and so we would have to put that in the film and the script would have to be re-written. We would just go forward with how we worked. I didn’t want talking heads, even though conventionally that is what you are supposed to do. I felt that there was a better and much more dramatic and emotional film to be done without cutting out the present, and by doing that it is much more difficult, it takes longer and is much more expensive. We only had deal for forty minutes of archive footage from the Formula 1 people, so I was cutting film often because my first cut was seven hours, my second was five hours long, then I had a three hour cut, and then we realized that we needed to make a change on a different scale. The producers agreed that the only way we could do this film is if we went back to Bernie Eckleston to renegotiate to see if we could have eighty minutes of footage and not forty. If we only had the forty then I was going to have to shoot interviews and cut interviews. I did shoot interviews eventually, but I just chose to keep the audio only, just the voices of people. I did not want to use the picture because I wanted to stay in the moment and, added to that, I could interview everybody but not Senna, and to me this would defeat the purpose; this was Senna’s story and we wanted him to narrate his own life story.

BT: One thing that is very interesting is dealing with details, because that makes the film very personal and like a drama. In a lot of documentaries, you see that attention to detail is sacrificed for telling the history of the events, but your film provides a unique blend.

AK: I think it is just the nature of his life and the man and how much of this material existed and the fact that we had a writer, a man who had so much knowledge on our team. He kept saying, “No, this is really important!” James, the producer, for him to be the spiritual ark of Senna’s life, we had to get out facts right about racing. We had to explain what Brazil meant and how he stood up for what he believed in and there were many things that we did not know about until we looked at the footage from Jean-Marie Balestre, the man who ran the sport. Senna’s life seemed to be like a movie, and everything he did seemed to come through action. Even when somebody had an accident, Senna would go there and we would actually go and look where the action would happen and his face was such that you could see what was always going on in his eyes, he has a way of telling the story through his face and when they speak it is so eloquent and intelligent and we were able to get all of these subtleties and details into the movie about his personal life, about his family life, about Brazi, about his character, and about his  rivalries; all of this was there and we just needed the time to work on an edit in order to make the film play, like a good script. But the problem is that if you had scripted it, no one would believe it. It was such an amazing journey and so tragic, that I think that the doctor—the relationship with the doctor, was just so brilliant and so sad when you realize how the film is going to be ending up. I had to show that it was the nature of the man; we were very lucky and we just kept looking and the more we looked, the more details that would come out that we could put in the film, but they were not tangents they were always a part of the story. His true character was always revealed through what he was doing.

rivalries; all of this was there and we just needed the time to work on an edit in order to make the film play, like a good script. But the problem is that if you had scripted it, no one would believe it. It was such an amazing journey and so tragic, that I think that the doctor—the relationship with the doctor, was just so brilliant and so sad when you realize how the film is going to be ending up. I had to show that it was the nature of the man; we were very lucky and we just kept looking and the more we looked, the more details that would come out that we could put in the film, but they were not tangents they were always a part of the story. His true character was always revealed through what he was doing.

BT: I know that this is a difficult way of working in the sense that you had to do the editing as well as writing the script and shooting and everything at the same time, but was there a final editing stage that you worked on and how long did that take?

AK: Honestly, it was always happening at the same time. That was the thing—it just wasn’t a conventional shoot. I don’t really like the rigid rules of filmmaking so, in this case, honestly we never hit the final length of the film until we delivered it. It was always too long and we always had too many scenes, so between the executives and the producers and the editors, they each had a favorite scene that they refused to take out of the film. I would screen the film and they would say, “This was great, but it’s half and hour too long.” I would cut half an hour, but then the executive would say, “Don’t take that scene out, I love that scene!” and then somebody else would say, “Don’t take that one out!” So we had this eternal problem of making the film hit the budget that we could afford and make it appealing to all. We asked ourselves, how long can this film hold someone who does not really know anything about racing? I would be really happy to make a two hour film, but we said that our 90 minute documentary should be no longer than 90 minutes. In the end, it went to 100 minutes. I’d say that there was a short “editing” period of maybe a couple of months where we were just working with the picture. All that time we were still putting in information and doing interviews, so it was never like, “Okay, we have got six months where we are just going to edit.” It never really worked like that.

BT: The editing and the music of Senna is amazing, please tell us how you dealt with those two aspects of your film?

AK: It was an interesting collaboration because the producer, the writer and myself all come from a drama background and a drama way of thinking, but the editors all work in documentary and are very brilliant. They are the people who really vibe on the film and really made it work and sorted the big sequences of the film. Then, of course, we have to mention our brilliant team of researchers lead by our archive producer, Paul Bell. He had a team in Sao Paolo, in Rio, in Rome, in Paris, and out in Japan, and they were the people finding the shots and finding the footage and actually giving it to us to cut. I knew from very early on that we were going to make this entire film from archive footage and, in this cas,e I had no control over the image quality. I didn’t care too much about the quality, I just wanted it to have an emotional fit—it needs to have the right story beat and the right character elements. I wanted the film to sound better than any other film and we wanted people to leave this film feeling totally Brazilian. We were working by Skype and I never used temp music and it was tough for this film because we did not own the footage, so I said to Antonio to just write some music from your heart. So most of the music in the film was written before the film was shot. The sound was tough as well because we could not go and recreate the sound of Senna driving a racing car because these cars are not driven anymore, and no one drives like he did. So all of these sounds that you are hearing came from these tiny microphones built into cars or audiocassette tapes, and we had to turn cassette tapes into Dolby Digital. So people usually see the picture side, but the audio really makes the film bigger.

and are very brilliant. They are the people who really vibe on the film and really made it work and sorted the big sequences of the film. Then, of course, we have to mention our brilliant team of researchers lead by our archive producer, Paul Bell. He had a team in Sao Paolo, in Rio, in Rome, in Paris, and out in Japan, and they were the people finding the shots and finding the footage and actually giving it to us to cut. I knew from very early on that we were going to make this entire film from archive footage and, in this cas,e I had no control over the image quality. I didn’t care too much about the quality, I just wanted it to have an emotional fit—it needs to have the right story beat and the right character elements. I wanted the film to sound better than any other film and we wanted people to leave this film feeling totally Brazilian. We were working by Skype and I never used temp music and it was tough for this film because we did not own the footage, so I said to Antonio to just write some music from your heart. So most of the music in the film was written before the film was shot. The sound was tough as well because we could not go and recreate the sound of Senna driving a racing car because these cars are not driven anymore, and no one drives like he did. So all of these sounds that you are hearing came from these tiny microphones built into cars or audiocassette tapes, and we had to turn cassette tapes into Dolby Digital. So people usually see the picture side, but the audio really makes the film bigger.

BT: Are you working on any new projects right now?

AK: Yes, I am, but I don’t have anything that is really that far developed. I am hoping to carry on doing documentaries and drama; it has been a great experience to make this film and I really enjoyed. I am going to go back to doing dramas but I would love to do more documentaries and I love the idea of experimenting and trying to push the genre in a different direction. That’s something that always excited me, so hopefully I’ll get an opportunity to find a subject that would excite me and be as powerful and emotional as with Senna. And thank god that the producers approached me and I feel very lucky to have had the chance!

BT: It seems that you are a very picky person when it comes to picking a subject on which to make a film, is that why you haven’t made too many movies during your life as a filmmaker?

BT: It seems that you are a very picky person when it comes to picking a subject on which to make a film, is that why you haven’t made too many movies during your life as a filmmaker?

AK: [I would make more films] If I had more money, which is a part of the problem. It would be much better if I could make two or three films at a time, but my brain does not work like that. I really find one thing and I have to become obsessed with it and then I really give everything—hopefully it works, and sometimes it doesn’t. When I finish a film, it really affects my mood on what I want to do next; that is what I can’t really explain. Each film that I have made is related to the film that I have made beforehand, and that process is somehow part of my experiences in life. You learn something and you go in on a journey as a filmmaker, and therefore the person you are when you finish is very different than the person you were when you began. So the choice of what I want to do next will be effected by where I am mentally. If I could find a way to change that, then that would be great because I would have made more movies because I instinctively enjoy feature films rather than working in television and commercials; there are other things that I could direct and I could have a different life, but I actually like taking my time and, for me, “less-is-more” is always going to be the way that I live my life. I like to be specific, I like to take my time, but it’s important to get it right.