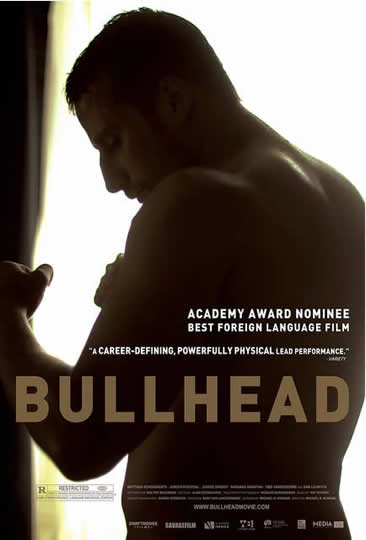

Michael R. Roskam’s BULLHEAD is a harrowing tale of revenge, redemption and fate. Domineering cattle farmer Jacky Vanmarsenille (Mattias Schoenaerts in a ferocious breakout performance), constantly pumped on steroids and hormones, initiates a shady deal with a notorious mafioso meat trader. When an investigating federal agent is assassinated and a woman from his traumatic past resurfaces, Jacky must confront his demons and face the far-reaching consequences of his decisions.

Michael R. Roskam’s BULLHEAD is a harrowing tale of revenge, redemption and fate. Domineering cattle farmer Jacky Vanmarsenille (Mattias Schoenaerts in a ferocious breakout performance), constantly pumped on steroids and hormones, initiates a shady deal with a notorious mafioso meat trader. When an investigating federal agent is assassinated and a woman from his traumatic past resurfaces, Jacky must confront his demons and face the far-reaching consequences of his decisions.

Bullhead is nominated for the Best Foreign Language Film Oscar.

Bijan Tehrani: Bullhead has the structure of a Greek tragedy, was this intentional?

Michael R. Roskam: I always describe it more as a tragedy than like a pure drama, it has a little Shakespearian style in the sense that the two mechanics have the same function in creating the main characters destiny, influenced by their stupidity and their stupid actions. For me, the best shots of the film occur in the quiet moments; it is silent but is saying a lot about what is happening and I love the landscapes of my country and that I could use them in this position. There is a lot of poetry and I was not looking for a Greek tragedy template, it gave me a lot of inspiration to create the tone myself.

BT: There is something when I watch your films; there is poetry in roughness and I think that your film is a good example of it.

MR: Yes, but it’s also very typical of the setting. We have a tradition of beauty and roughness in my country of Belgium. There is a lot of rough characters who have their feet in the mud, they are soaked in the land where they live—the farmers and the guys who work on the field—and they have seasons and it is about minus twelve, so it can get hot and cold but it is beautiful, and autumn is even more beautiful. So we do have these landscapes and the land is always interfering a lot. I think the poetry with roughness is a little tradition that we have; we have those characters in literature. Obviously,  Belgium is a country that was created by the European powers and, through the years, this country has been the battlefield of Europe, so our soil is soaked in blood even though we were not the guys that were fighting. Now for 60 years there has been peace and no war, so I think this influences the characters because they still battle and in a way they find glory in a tragic destiny. That is what I was trying to convey.

Belgium is a country that was created by the European powers and, through the years, this country has been the battlefield of Europe, so our soil is soaked in blood even though we were not the guys that were fighting. Now for 60 years there has been peace and no war, so I think this influences the characters because they still battle and in a way they find glory in a tragic destiny. That is what I was trying to convey.

BT: You also have a Shakespearian sense of humor, especially with the two mechanic characters.

MR: Absolutely, it was a tricky one because the balance was very hard to find between the two themes, this is why I chose tragedy as a style because tragedy allows humor and it give opportunities to give the audience a chance to breath. It is also about life; sometimes life is sad and sometimes it is funny, you know. Life is kind of tragic either way, we all know we are going to die but there are still a lot of fun things to do in life. The knowledge of our destiny does not make us sad all of the time. Humor is a very important element in my films, so in this films the mechanics are like the characters in Hamlet and The Hidden Fortress, where you have comedic actors in a very dramatic story; it works and when you have these kind of epic stories it adds something important to it.

BT: How did you come up with this story actually, was it based on an actual person?

BT: How did you come up with this story actually, was it based on an actual person?

MR: No, not completely. T he mafia scene was real—that was based on a real situation in my country, most notably in the 90s, when the criminals were exposed to authorities when they killed a federal inspector. He was working with the FDA in Belgium, a kind of Elliot Ness kind of character; I decided that I wanted to make this tragedy/film-noir kind of movie, and also a very good tragic personal story. So I invented this story and it was inspired by events in the industry, because if not, the audience would know what is going to happen. I can say I was inspired by the way they treat young male pigs when they are born. That is how it started to run, and suddenly this whole hormone thing became a metaphor and when those things connected I knew that I had my story, and that took me about three years.

BT: There is something about Jackie’s character, where it seems that his life is determined by something that happened in his past and it is almost like he cannot make choices.

MR: Whatever he does, he would end up at the same conclusion, that is something that I was thinking of when I was writing the story and I was looking for the tone of the movie. I was trying to find a certain thing that would give people the impression that it took place, it already happened and now I am going to tell you the story. It is different when you make believe that the story can go anywhere, and here I just wanted to make the people feel that I am telling them the story even though the ending is tragic because the ending will make you understand something. So for me, it was that the ending existed and it is in the journey that the true core of the story lies. I think tragedy has this moment and the ending is there, and I am fascinated with those kinds of stories.

BT: How did you go about casting the lead role?

MR: We met when we were doing a short film in 05′ and we knew that in the small Belgian cinema world that there was this young actor who everyone was saying was brilliant. He was the son of a legendary stage actor. We knew that he had inherited the acting genes of his father, and I told him about the story I had in my head. He said that it sounded good and he wanted to know if he could read something, so I gave him the first version of the script and it was a really bad one, but he knew that the story was there and he said that he wanted to do this. He had to gain 60 pounds for the role and I knew that he was the guy who could handle this on all of the levels, because he is just a brilliant actor. I wanted to make the audience believe that the weight on his shoulders was not just, physical but also psychological. He has this third vision of masculinity and he also had great eyes; what he could do with just looking, it was kind of a Beauty and the Beast kind of thing. He was a major support to me because I knew the film would be a risk if the main actor could not portray a real person. I knew that if he could not do that, then the film would be a disaster. But with him, I knew that I was safe, that I could write with confidence and do whatever I wanted with that character.

BT: How did you come up with the visual style and the look of the film?

MR: I worked with my people, my crew, and I have known them all for a really long time. My DP and also my composer, we are all friends and we worked and talked and referred to Belgian painters and French Painters like Rembrandt. We never really showed pictures or photographs and we also decided to create a very basic concept of composition and movement of camera, because we were very limited on time and we knew that we could not afford to play around and try things out. I knew that I did not want a shoulder camera—I wanted a camera that only moves away from the main camera, and when he is watching, we will only watch it from behind his back. We then knew that we would only make this choice if this was the only choice we had going into the scene. So, at the start, there was a framing concept and a moving concept, and we developed our visual style over the years that we worked on the film.

BT: The score is mixed very well; it is almost hard to notice.

BT: The score is mixed very well; it is almost hard to notice.

MR: Yes, it is very depressing and actually sad because people always say they loved the music but they cannot remember it. My composer says that this is the way that it has to be, unfortunately, and people will only notice the music the second or third time. The music is, for me, a part of the landscape and it is something that has to create emotion. Sometimes, thirty seconds can seem short, but with the right music, thirty seconds can feel like thirty years. When we talked about music with the composer, we said that we would not put the music upfront, but instead we would put the music at the crucial moment of a scene or an action; the music would take place and it would be like an echo of emotion.

BT: Bullhead is nominated for the Best Foreign Language Film Oscar, how important is the nomination to you and how will winning the Oscar help your film career?

MR: Already, the nomination gives me a lot of credit and a lot of opportunities—It is starting, and I feel the difference. If I win the Oscar, it would be more, so I am just happy with the nomination and the opportunities that I have been created with this nomination. Even if we don’t win, we might have a chance to win and, right now, I am just going to enjoy the moment and also enjoy it if my colleagues win.

BT: What is your next project?

MR: I am developing projects and then I will chose which one I will do. I was doing a story by myself which is called “The Faithful”, which is a Brussels, Belgium based story. This might not happen right now, but maybe later because I am having a couple of opportunities in the US to do some movies there. But again, I am just doing some reconnaissance and just trying to meet people and get some opportunities so I can continue to work the way that I work. The one thing that no one can touch is my voice, and I want to keep that. I hope that I can make the movies in the US because there is a high concentration of good talent, and there are a lot of means to make good movies there; I will see what happens.