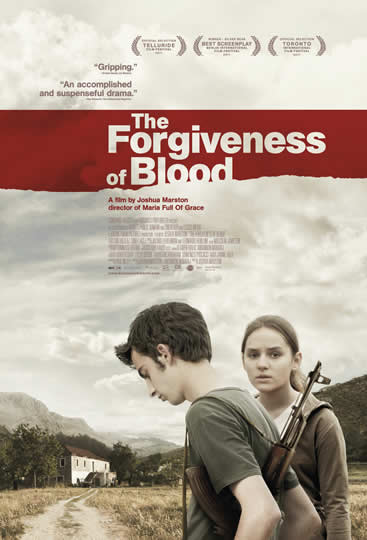

Winner of the Silver Bear for Best Screenplay at the Berlin Film Festival, the powerful and richly textured second feature from Joshua Marston (Maria Full of Grace) focuses on an Albanian family caught up in a blood feud. Nik (Tristan Halilaj) is a carefree teenager in a small town with a crush on the school beauty and ambitions to start his own internet café. His world is suddenly up-ended when his father and uncle become entangled in a land dispute that leaves a fellow villager murdered. According to a centuries-old code of law, this entitles the dead man’s family to take the life of a male from Nik’s family as retribution. His uncle in jail and his father in hiding, Nik is the prime target and confined to the home while his younger sister Rudina (Sindi Laçej) is forced to leave school and take over their father’s business. Working with non-professional Albanian actors and a local co-writer, Marston boldly contrasts antiquated traditions with the lives of the young people whose future is put at risk by them.

Winner of the Silver Bear for Best Screenplay at the Berlin Film Festival, the powerful and richly textured second feature from Joshua Marston (Maria Full of Grace) focuses on an Albanian family caught up in a blood feud. Nik (Tristan Halilaj) is a carefree teenager in a small town with a crush on the school beauty and ambitions to start his own internet café. His world is suddenly up-ended when his father and uncle become entangled in a land dispute that leaves a fellow villager murdered. According to a centuries-old code of law, this entitles the dead man’s family to take the life of a male from Nik’s family as retribution. His uncle in jail and his father in hiding, Nik is the prime target and confined to the home while his younger sister Rudina (Sindi Laçej) is forced to leave school and take over their father’s business. Working with non-professional Albanian actors and a local co-writer, Marston boldly contrasts antiquated traditions with the lives of the young people whose future is put at risk by them.

Bijan Tehrani: My first question is how did you come up with the story for The Forgiveness of Blood?

Joshua Marston: I was fascinated when I first read about the tradition of blood feuds in Albania, but my astonishment came from the fact that the feuds are still carried out in present day Albania. Even though it is 2012 and they have cell phones, internet, and TV, people are still caught in unbelievable circumstances because of this centuries-old legal code. I learned a lot about the blood feuds, and then developed the story about this contemporary teenage boy whose life is changed by the actions of his relatives and the presence of the blood feud. I worked a great deal with producer Paul Mezey, who was my producer on Maria Full of Grace as well, and he helped during the writing process. The story evolved as we tossed around ideas made discoveries, and we managed to put together an impactful film script.

BT: How did you go about shooting the film, especially in a country where there are not many films made, and how did you go about finding the actors for the part?

JM: Casting was very difficult. It meant finding real teenagers to play the parts because there are no professional teenage actors in Albania. We had to go from school-to-school and, over a six month period, we went to fifty institutions and saw about three thousand kids. We would do initial interviews with every student for 3 or 4 minutes each so we would find out who they were, and then we would call back the fifteen most interesting kids in the school and ask them about their lives, about being a teenager in Albania. I would steer the conversation in different directions and improvise a bit to reveal more of their character. After many thousands of kids, we were fortunate to find these two great young actors.

BT: How did you work with your actors?

JM: We began, first of all, by just creating the relationship, the family relationship. I started with improvisation and just finding their characters and finding as much about them and how they should interact. So we did improvisation that related to homework and studying and partying, and also trying to get the actors to feel comfortable being brother and sister. Then I added in the actors who were to play the mother and father—eventually we had the whole family, along with the grandfather, doing improvisation and, when we had the whole family cast, we started doing scene from the script.

BT: Did you also have a few professional actors working on the film?

JM: Yes, of course. Though, we found our main actors through our search in Albania.

BT: It can be a challenge to have professionals and both amateurs on the film, but you have balanced the two very well in this film.

JM: I think that is because the non-professionals were mature enough to act very professionally, and the professionals were relaxed enough to understand the circumstances and how they could help the production. What I mean by that is that the professionals really went out of their way to make the non-professionals feel very comfortable. The actors who play the mother and father are acting teachers, so they are used to working with kids who are just beginning to act. They were very good at making the kids feel comfortable, explaining certain things about acting, and coming up with exercises to help them. The performance success came from the actors, but it was also about rehearsing the script and about these kids learning the trade of acting.

BT: Did you allow any improvisation on the set?

JM: A little bit but, by the time we were shooting, we were shooting the script.

BT: There seems to be a connecting theme between this film and your previous films, was this intentional?

JM: I think that there is continuity in my style and it seems interesting. There are certainly parallels in that some of my films are about young characters that are growing up and becoming mature. My films are mostly realist in their style, in terms of the way their camera shots are designed. It was interesting to see how the films are similar and different in their stories.

BT: How did you come up with the visual style of this film?

BT: How did you come up with the visual style of this film?

JM: One of the things that were very important from the beginning was to find a way visually to underline the drama and to underline the importance between the outside and the inside. This is the story about a boy who cannot find his way out, so this meant that, when we were thinking about the visuals, we were very aware about the windows, the doors, the light, the sunlight, the outside and the inside—sometimes, these can represent home and security, and other times they represent fear and threats. In many respects, those differences between the outside world and the inside world form the vision of the character.

BT: How have Albanian audiences reacted to the film?

JM: The film was been released in Albania in September, 2011 and it broke box office records. it was especially popular with teenagers and it has received very positive reactions, all the way to the point where the Albanian selection committee selected this film to send to the Academy Awards in the foreign language film category. Fans were angry and disappointed that the film was rejected because of a technicality, but it was an honor that the Albanian community wanted the film to be represented in the Oscars.

BT: Please tell us about the US release of the film.

JM: The U.S. release was on February 24th in New York, and then in March it will expand to other theatres in other cities.

BT: Maria Full of Grace had a lot of success. When I first saw the film, it did not seem like it was made by a first time film director; your surprised a lot of people and experienced some success. How do you anticipate the success of this film?

JM: I hope that people will come and see it because, on the one hand, it is fascinating as a depiction of a small country that people know very little about, but on the other hand, the film has very universal themes. I think that American audiences will find it fascinating and relatable.

BT: Do you have any new projects lined up?

JM: I’m getting ready to do a film that will be shot in the US this summer.