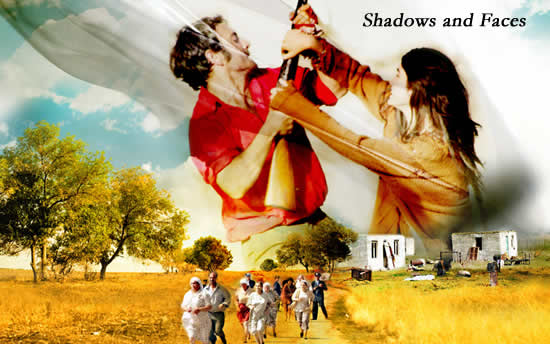

I had an opportunity to interview veteran Turkish film director Dervis Zaim, who served as the Jury president of The Los Angeles Turkish Film Festival’s inaugural festivities. Zaim, who has long taught at Bogazici University in Istanbul, has influenced a generation of younger filmmakers. His film “Shadows and Faces” (Gölgeler Ve Suretler-2011)), winner Best Film- 22nd Ankara International Film Festival, opened LATFF.

I had an opportunity to interview veteran Turkish film director Dervis Zaim, who served as the Jury president of The Los Angeles Turkish Film Festival’s inaugural festivities. Zaim, who has long taught at Bogazici University in Istanbul, has influenced a generation of younger filmmakers. His film “Shadows and Faces” (Gölgeler Ve Suretler-2011)), winner Best Film- 22nd Ankara International Film Festival, opened LATFF.

Robin: I understand that you have done a series of films, this is the end of the series, and all of them have an element of traditional art as the subtext.

Dervish: I am trying to basically translate the structure of traditional forms into cinematic language so that I can find a new and fresh way for cinematic storytelling. I am doing this in order to create some little changes with mainstream narration. You should either have a simplistic approach to cinema or another alternative is to play with the structure of the cinematic narration. Basically I choose to play with the structure of the Narration and while I am doing this I take the inspiration from the traditional Middle Eastern Mediterranean art forms such as Ottoman calligraphy, Ottoman miniature painting, marbling or shadow play puppets.

Robin: Can you describe how you integrated the ideas or structures from these art forms?

Dervish: For the sake of description I can say that I used traditional art form of Marbling in “Elephants and Grass” (Filler ve Çimen). In the fourth film, “Waiting for Heaven” (Cenneti Beklerken), I used Ottoman 17th century classical miniature painting for the structure of the film, and in the 5th film “Dot” (Nokta) I used Ottoman calligraphy and in the last film “Shadows and Faces” (Gölgeler ve Suretler), I used shadow theatre puppets for the cinematic language. Nowadays especially outsiders demand that if Turkish cinema is going to be unique, different from the mainstream cinema, it should be minimalist. I have no objection towards minimalism but if someone says to me that this is the track that you are going to launch yourself, I do not accept this. With all respect to minimalism (I love it), however if somebody tells me what I have to do in order to be accepted by them, this is a not a correct approach. This is the reason I am using this other method, which is playing with the structure, inspired by traditional art forms.

Robin: Just the structure or the process? For example there are constants in the miniatures like the color palate. Did that effect the way that you thought of the film where you used the miniature as inspiration?

Dervish: Yes for example in Dot (Nokta) inspired by Ottoman calligraphy, I used the concept of “Ihcam” which means to write the calligraphy in one stroke without interrupting, without taking your hand from the writing once from beginning to end. So based on this notion I choose to tell the story in one shot without any cuts. So not only content but also at the same time inspired by the art form itself and this is more or less the same for all of the films. Events within the film, whether past or present, are narrated as though happening in real time. There are no interruptions, no cuts, meaning the story is told ‘in one go’ to evoke the intended sense of continuity.

Even in the case of flashbacks, I plan to carry on using this same technique. While, for instance, the film’s central character Ahmet operates in the present tense, he occasionally recalls the past, at which point the

narrative backtracks to reveal those past events shaping his present experience. But in portraying the past and present, the film deliberately eschews formal cuts or other transition techniques used to differentiate the two tenses. I attempt instead to present events in the single stroke that characterizes “ihcam” so that events elide into an unbroken continuum. In this sense, time and place are constructed as an interconnected whole.

Having said this I do not want to make myself out as an experimental filmmaker, because cinema has a commercial aspect and I do not want to have my films play for 50 people. I’m interested in finding and communicating with the audience but at the same time, my intention is to add other levels to my films, so that people who love and want to see other things in cinema can find such things. This is the basic approach while ı am constructing the films.

Robin: can you explain in more detail how you transposed the ideas of the other art forms into the films.

Dervish: For example miniature painting: what is my approach toward miniature and how do I translate it into film language? Look at classical Ottoman miniature. I tried to interpret as follows: the space and time in the classic miniature painting is used in a different way, maybe in a cubist manner. I am not suggesting that Ottoman Classical miniature artists are an early example of cubism. But I used the example to give you a better understanding. Ottoman miniature artists may use X time and Y time side by side in order to create richer, broader explanations and narration. They may also use z location and f location side by side in the same miniature to have a richer description of events.

For example we are talking here in this time, but they can also put a scene here which occurred two months earlier or which will occur three years later in the same frame, to make this scene richer and more expressive for the object of narration. By doing this they will problematize the space and time like cubists do. I use this tool in the film in some places. I need to emphasize that I use this technique only in some places in order not to get an experimental film in the final point.

The film focuses on relations between the artist and the state against the backdrop of a 17th century revolt, which resonates with contemporary issues and discourse. “Waiting For Heaven” centers around two visual art forms–the miniature form of the East and Renaissance art of the West–and seeks to conceptualize the probable interface between the two forms. In the last analysis, it is asserted that the probable interface between these two forms represents an enriching, rather than impoverishing, development. Thus, subjects, relative to the characteristics of style, structure, and visual elements, are shaped by this perspective and this belief.

The film focuses on relations between the artist and the state against the backdrop of a 17th century revolt, which resonates with contemporary issues and discourse. “Waiting For Heaven” centers around two visual art forms–the miniature form of the East and Renaissance art of the West–and seeks to conceptualize the probable interface between the two forms. In the last analysis, it is asserted that the probable interface between these two forms represents an enriching, rather than impoverishing, development. Thus, subjects, relative to the characteristics of style, structure, and visual elements, are shaped by this perspective and this belief.

Even though the film intends to utilize the art of miniature, an art that is generally assumed to have a weaker relationship with “reality”, I believe that we should not disrupt the three dimensional perception of “reality” of today’s film viewer. For this reason, as I developed the style, the degree of use of traditional art forms did not extend all the way to three dimensional perception; care was taken that the tone of the film not be “entirely stylized.” The driving factor underlying this approach is that the film also touches on Western art and the scope of its form. It is common knowledge that when Renaissance paintings are compared with miniature paintings the former seem to represent more “realistic” depictions. Thus, this film is an attempt to debate the contiguity of Eastern and Western painting (a discussion of what may arise from their interaction when they overlap under certain circumstances); as such we believe that an entity can be composed of a coexistence of very different styles. For example, I make wide use of miniature art and the cinematic projection of that art up until the last phases of the journey of the Eflatun character. However, from the point in the film when Eflatun comes into contact with Velazquez’s painting, he makes more ready use of a Renaissance style of light and color.

Robin: This is interesting for me, late Gothic painting and early Japanese scrolls share these qualities, both early mediums which also tell a story in very sophisticated ways, conflating time and space, not to say they do it in the same way but those dynamics are also present in those early mediums. I think it is fascinating that you have used this here. I can’t wait to see the film to see if I can glean it from the film. Can you talk about how you got involved in the festival here?

Dervish: Well the leading organizers of the festival are my ex students at the Bogazici University in Istanbul, Cenk Erturk was my assistant director on two of my films. So these young and brilliant guys wanted to make a important thing here and they want me to be in the jury so I…

Robin: Apparently they looked at two hundred shorts and presented you with 10 finalists.

Dervish: As members of the jury, we had to choose one best film and two special jury awards among ten pre-selected films. I think the organization is amazing. Although it is their first time here, I think they made a wonderful selection. Moreover, they invited established Turkish film directors such as Kaplanoglu and Ustaoglu here for a short film festival, plus all of the participants and competitors. They hired the Egyptian Theatre for five days. They made a reception for opening night and I had a chance to see that there are a lot of volunteers and attendees around. For a first festival, it was amazing and I hope it is going to continue in a much wider context.

Robin: Do you think you will stay involved in it?

Dervish: Yes, because these are my students, my assistant.

Robin: What is your next film going to be?

Dervish: I already shot it (Devir- “Circle”) and you are the first person that I am announcing this to. I shot with three shepherds in the mountains in Anatolia and we are now beginning to edit the film. Complete non-actors. The shepherds play shepherds in the film. Its not a hard core neo-realistic film even though it is effected by neo-realistic domain. I again play with certain things in the narration. Turkish Cinema generally employs Italian Neo Realism and it uses it in a classical way. Here I don’t follow the same route. So we will see.

Robin: The classic period of Turkish miniature is which century?

Dervish: I used the classical period, which is the 17th century. Matrakçı Nasuh is the artist that inspired these miniatures.

Robin: In “Shadows and Faces” (Gölgeler Ve Suretler which opened this festival, can you explain how shadow puppets became the shell or the structural grain of the film?

Dervish: When it comes to shadow I go to the Greek philosopher Plato and the cave metaphor. The film is inspired by Plato’s ethic and aesthetic discourse but I am very careful about Plato’s argument about Harmony because it asserts the idea that harmony is the key for happiness and I am not sure about this. Nazis are very happy while they are burning 6 million Jews. They may feel harmony while they were doing terrible things. So I tried to be careful about the harmony concept and discourse while ı am inspired by Plato’s writings.

When it comes to evil and the dark side, and using shadow to show these, one should be aware that the shadow side will be always there. It will have nothing to do with harmony. You should feel your dark side and communicate with it, otherwise shadows will overpower you and make you a slave; this is the idea behind “Shadows and Faces”(Gölgeler ve Suretler). I focused on Cyprus and the problem between the Greeks and Turks in the Islands. The shadow is a common cultural artifact of the island so I think I can use this cultural form to describe the situation, or the human situation in the island. I use it to show the effects of the shadow or the evil side of humans. I also try to interpret idea of Shadow Theater to enrich the style of the film. To develop the visual structure of the film, I set to work by interpreting the original Karagöz screen on which the shadows of the puppets are projected to perform the Karagöz play. In some versions of the traditional Karagöz play, a synchronizing approach is used where the screen hosts the moments of past, present and future simultaneously. With an approach similar to the traditional method, I, at time, seek to form a  synchronizing logic by making the past, present and future of the film appear together on the cinema screen. The transition parts appearing in four scenes of the film may provide examples as to how this approach is implemented in cinema. Some plans of the film transform into photographs, and each photo (“plan”) is picked up by a human hand after being transformed. In fact, at different times and places, the characters hold in their hands the previously transformed shots of other characters or themselves. Thus, similar to the Karagöz screen, in the film, the moments pertaining to past, present and future appear simultaneously on the same scene. These plans (images), which turn into photographs in the film screen, are actually standing on a table in the living room of the characters. On that table, the past, present and future of the film appear in photographic form, waiting to be noticed by the characters and the audience. With these aspects, the film makes references to the Allegory of the Cave of the ancient philosopher Plato (who also had a strong influence on Islamic aesthetics) and to C. Gustave Jung.

synchronizing logic by making the past, present and future of the film appear together on the cinema screen. The transition parts appearing in four scenes of the film may provide examples as to how this approach is implemented in cinema. Some plans of the film transform into photographs, and each photo (“plan”) is picked up by a human hand after being transformed. In fact, at different times and places, the characters hold in their hands the previously transformed shots of other characters or themselves. Thus, similar to the Karagöz screen, in the film, the moments pertaining to past, present and future appear simultaneously on the same scene. These plans (images), which turn into photographs in the film screen, are actually standing on a table in the living room of the characters. On that table, the past, present and future of the film appear in photographic form, waiting to be noticed by the characters and the audience. With these aspects, the film makes references to the Allegory of the Cave of the ancient philosopher Plato (who also had a strong influence on Islamic aesthetics) and to C. Gustave Jung.

Robin: How did you use calligraphy?

Dervish: In each of these films I have a character-an artist. This artist has a problem at the beginning of the film and this problem is parallel to the art form itself, whether it be calligraphy or shadow painting or puppets or marbling, it affects both the objective character and the spin of the narration, gradually I find other subplots, which trigger from this main point of attack. This is the basic structure of my films. I will give you the example of how ı use marbling. I take the Ottoman art of Ebru (marbling) as a leitmotif and through the form and references of this traditional art, ı seek an optimal cinematic form to discuss the corrupt relations between the Turkish state and local mafia. The art of Ebru creates truly unique works with unrepeatable patterns. Even when the artist intends to reproduce a certain work, each attempt results in a different piece due to the unrepeatable character of conditions and the nature of the material. The Ebru artist creates works through a process that swings back and forth between the two poles, with coincidence and chance on one side, and the artist’s desires and decisions on the other.

In “Elephants and Grass”, I take the creation process of the Ebru art as the reference point in developing the form of his film. The film revolves around the intersection of the destinies of numerous characters and stories through coincidence and chance. With this aspect of its form, “Elephants and Grass” almost resembles the creation process of an Ebru work, and parallels the similarity of form. The film’s content also discusses the themes of coincidence, necessity and freedom. The layered structure of the film and the impression created by this structure make the audience feel that they are before a completed work of Ebru art.